It doesn't matter how bad or wildly untrue an idea might be; it is a near certainty that one can find an academic somewhere who is willing to embrace it.

science policy

The other night, I had dinner with one of my best childhood friends who became an OB/GYN. She has three amazing children and was pregnant with her fourth.

Trigger warning: She ordered a glass of wine. And drank it.

In foreign policy, it is difficult to state anything with certainty. Intelligence agencies have sources that journalists do not. As a result, publicly available information is often incomplete.

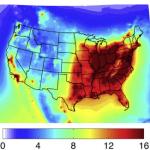

Every so often, the media likes to warn us that we're all dying from air pollution.

In order to capitalize on current events and our hyperpartisan climate, science news outlets increasingly feel the need to weigh in on how day-to-day political affairs will affect science.

Last year, Bayer announced its intention to purchase (in cash!) Monsanto.

Recently, I gave a seminar on "fake news" to professors and grad students at a large public university. Early in my talk, I polled the audience: "How many of you believe climate change is the world's #1 threat?"

President Trump has convened a panel to address America's opioid epidemic. Its first mission should be to find convincing data to identify the actual cause(s) of the problem.

Scientists are humans, too. And, just like other humans you know, some of them aren't very good at their jobs. There are three main ways in which scientists can mess up.

The war on expertise is not a new phenomenon.