The constant chirping sound in hospitals is the wide range of alarms notifying nurses and physicians of conditions requiring their attention. In a survey of 348 nurses, 65% found the alarms disruptive of patient care, and the frequent false positive “crying wolf alarms” negatively impacted their confidence in the alarm systems. Alarms are so frequent and often either wrong or unimportant that upwards of 90% may be ignored. [1]

In the last week, I have seen headlines regarding the “pollen apocalypse” – an event presumably “involving destruction or damage on an awesome or catastrophic scale” and weather reports telling me that 35 million of my fellow citizens were at risk for thunderstorms and possible tornadoes. And that doesn’t begin considering the headlines from our political and financial worlds. The constant diet of alarms, like the nurses' experience, disrupts our lives and fosters a lack of confidence in the social alarm systems we call media.

Back on the savannah, when an alarming, dangerous situation is perceived, we act to fight or flee and ask questions later. Put in more scientific terms, we respond to danger first with an intuitive, evolutionarily adaptive action; and later use our analytic story-building brain, the voice in our heads, to explain what we did. The constant presence of alarms attenuates both the autonomic and narrative response, but more so the narrative because the autonomic response keeps us alive.

In a review of chronic stress on our bodies and minds, it is the scientific consensus that it:

- physically alters our brains.

- affects our emotional, autonomic response. The “how of stress” can sharpen and decrease our memory based on the timing of the alarming information. But “the why of stress” is the afterthought of the physiologic response, and chronic stress reduces that cognitive function.

- depresses our immune system’s responses.

- increases our heart rate and leads to hypertension.

- alters our appetite and intestinal absorption of nutrients.

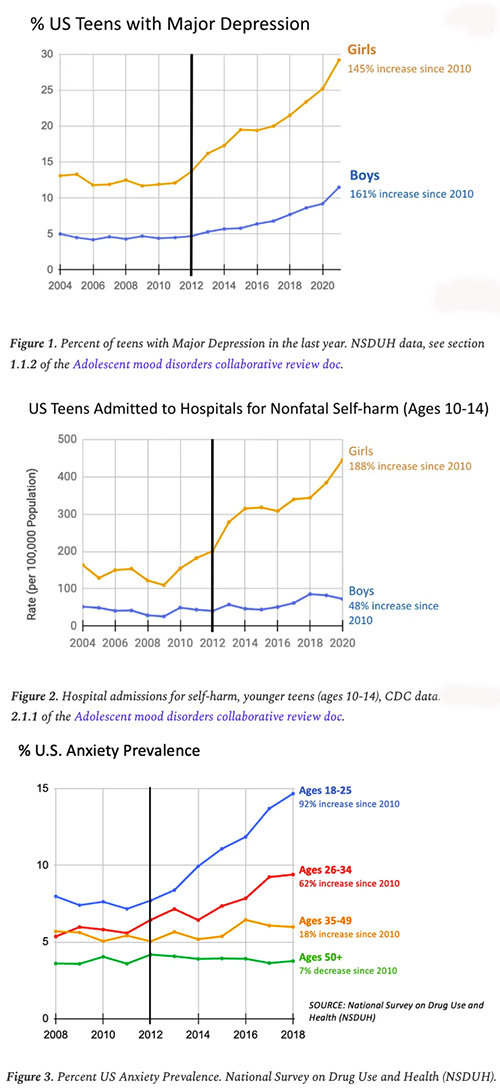

Perhaps a more concerning sign comes from the canaries in our alarm coal mine – teens, who are of an age when external opinion is imperative and feast on social media. Here are some data to consider. (Whether girls are more sensitive or more demonstrative in sharing their feelings is something we might discuss another day.) Still, our most vulnerable are experiencing mental harm from what is perceived as anxiety but results from chronic stress. And these findings are not confined to just the U.S.

Perhaps a more concerning sign comes from the canaries in our alarm coal mine – teens, who are of an age when external opinion is imperative and feast on social media. Here are some data to consider. (Whether girls are more sensitive or more demonstrative in sharing their feelings is something we might discuss another day.) Still, our most vulnerable are experiencing mental harm from what is perceived as anxiety but results from chronic stress. And these findings are not confined to just the U.S.

Our media diet is a powerful social determinant of our health

Just as much, in my view, as our level of education or access to care. When Marshall McLuhan declared that “the medium was the message,” he meant more than whether it was words or pictures. The media has given lip service to their impact on our analytical thinking and the divisiveness of our politics.

“You notice when you take a little time off how unbelievably stupid most of the debates you see on television are. They’re completely irrelevant. They mean nothing. In five years, we won’t even remember that we have them. Trust me as someone who’s participated.

Yet at the same time — and this is the amazing thing — the undeniably big topics, the ones that will define our future, get virtually no discussion at all: war, civil liberties, emerging science, demographic change, corporate power, natural resources. What was the last time you heard a legitimate debate about any of those issues?” - Tucker Carlson

But the media, in all of its platforms, has not addressed in any substantive way its underlying business model – if it bleeds, it leads, fear and alarm remain the strongest pulls on our attention. Fear and alarm as a daily diet are making us ill.

The media has done a poor job of policing itself; at its current scale, policing itself is impossible – maybe the much-hyped artificial intelligence can be brought to their aid. Government lacks the deft touch necessary to reduce alarming headlines; their regulatory guidance will be too much, too late. But the means to reduce the problem, fortunately, lies with us. To channel another meme of the 60s, it is time to turn on and tune in to our real lives with family and friends and drop out of the media. Take that media holiday and see if you are not just as informed and perhaps a bit more relaxed when you dip into the infotainment stream for just 15 minutes a day. Maybe even consider intermittent fasting from the media.

[1] I can attest to that from my hospitalization when I accidentally pulled off my EKG leads. Based on the monitor in the “Intensive” Care Unit, which was presumably being watched, I was “flat-lined” for up to 20 minutes with a bell going off every 30 or 40 seconds before a passing nurse noticed.