“Bad is stronger than Good.”

The "fight or flight" and "rest and relax" responses represent distinct physiological adaptations. The sympathetic nervous system primes the body for immediate action in the face of perceived danger, while the parasympathetic nervous system gradually promotes relaxation and digestion. The balance between these two responses is essential for overall well-being. However, fear sells far more than good tidings when sharing information in conversation, gossip, or the news. The phrase, “When it bleeds, it leads,” has been translated in psychological terms to a negativity bias; potential danger is more powerful than potential benefit. [1]

Studies in communication have highlighted that factors such as authority, physical attractiveness, and in-group coalition [kith and kin] influence the perceived credibility of information sources. The hypothesis presented in this study posits:

“all else being equal, a source of threat-related information may be intuitively judged as more competent than a source that does not convey such information, thereby increasing the motivation to transmit the negative message information.”

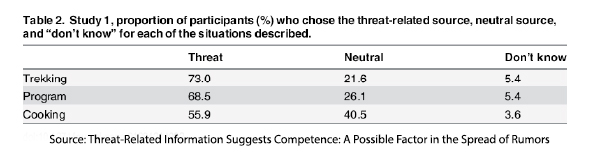

To test this hypothesis, researchers conducted five experiments using descriptions of six products [2], with variations in the presence of threat-related, negative, and neutral sentences. Participants, all US citizens recruited from Amazon M-Turk, were asked to evaluate the competence of the information sources.

In the first two studies, participants compared descriptions of products, differing only in the presence of neutral, negative, or threat-related sentences. [3] After reading both descriptions, they were asked which author seemed more competent. The findings consistently revealed that sources invoking a threat were deemed more authoritative and not by a little. The second study, where a negative sentence replaced the neutral sentence, suggested that simple negativity was not the primary factor driving perceived competence.

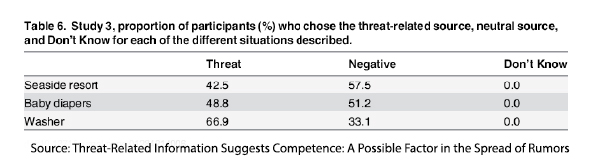

In the third study, the researchers sought to understand whether the threat being a “perceivable danger” affected the choice. They used three different products: a seaside resort, a new baby diaper, and a new washing machine. Only the threat related to the washing machine, representing a perceivable danger, the risk of damaging clothes [4], resulted in the perception of the source as authoritative. When the danger was negligible, neither a threat nor a negative sentence conveyed authority.

All three studies consistently showed that sources providing threat-related information were judged as being more competent than those not conveying such information. The question arose whether this judgment was based on the threat itself or the perception that the non-threatening source was negligent. Did contrasting views make a difference?

The fourth study introduced sequential presentations of threat and non-threat versions. , aiming to gauge how helpful participants found the information. The researchers reasoned that if the danger were the most salient, it would be considered most helpful after reading the neutral version. If the neutral were considered more negligent, it would be regarded as far less helpful after reading the threatening version. As it turned out, both considerations enhanced the perceived competence of the threat source, its perceived danger, and the perception that the neutral source was "insufficient."

“This effect [communication of threat information is associated with competence] is driven by a specific intuition of competence, not by a general “positive glow” [or greater honesty] associated with the particular source.”

In the final study, researchers investigated whether the perception of competence extended to positive feelings, such as honesty. Participants were asked about competence, honesty, and pleasantness. The study affirmed that the competence effect from threat-related information was driven by a specific intuition of competence, not a general positive glow.

The author of threat-related information was judged more competent in a variety of situations and was enhanced if the threat was deemed credible and in the presence of contrasting information from different sources.

“The Sky is Falling”

The childhood story of Chicken Little bears directly on this study. Chicken Little interprets a seemingly innocuous event as a sign of impending disaster and rushes to spread the alarming news. The other barnyard animals, just like the human participants in this study, assume Chicken Little’s competence because of the threat and salient nature of the message. Henny Penny, Ducky Lucky, and Turkey Lurkey join the commotion, amplifying the fear; humans “like” and retweet.

The story of Chicken Little serves as a timeless reminder of the dangers associated with unchecked fear and the importance of maintaining a rational perspective amid uncertainty. In healthcare, where the concept that "bad is stronger than good" is familiar, this study aligns with the understanding that potential danger holds more sway than potential benefit. Critically, it is the salience of the danger that triggers these responses. The findings underscore the need for nuanced communication strategies, recognizing the impact of fear and threat-related information on perceptions of competence.

[1] This is a well-known concept among physicians. It is far easier to motivate an individual to a particular treatment when they have a 5% risk of dying rather than a 95% chance of living.

[2] “The products described were (1) a guided trek in the Amazon, (2) a data-base computer program, (3) a cooking recipe, (4) a washing machine, (5) baby diapers and (6) a seaside resort.”

[3] Threat-related sentence: “If you press control keys during installation, the software may damage your hard disk.” Neutral sentence: “During installation the program will check that your hard disk is in good condition and report on how reliable it is.” Negative sentence: “The program can take a long time to master because the instruction manual is very complex.”

[4] The threat at the resort was that the gates closed at midnight and that improper folding might result in a rash for the diaper scenario.

Source: Threat-Related Information Suggests Competence: A Possible Factor in the Spread of Rumors PLOS One DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128421