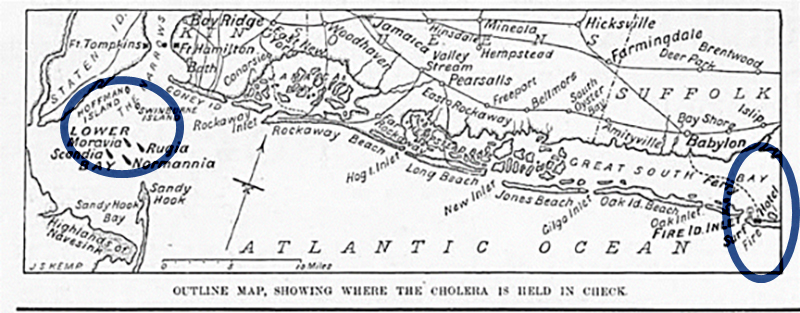

Late on August 29, 1892, the SS Moravia crept into NY Harbor carrying two passengers with cholera, seeding the 1892 American cholera epidemic. Not particularly dramatic in terms of the number of deaths, the epidemic was significant in governmental conflict regarding who makes the epidemic rules – and who suffers from them. Four days later, two more ships docked bearing cholera patients, the SS Normannia and the SS Rugia.

All had departed Hamburg, Germany, where the epidemic began several days earlier. Even then, international transport of disease was a concern, and countries had consul stationed in Hamburg, a leading international port, to prevent ships from sailing in the event of an outbreak. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Germany hid the outbreak until after the three ships left port and were well on their way to their promised land.

The Moravia carried only steerage passengers, virtually entirely, poor Russian Jews fleeing the pogroms. This fed nicely into the existing stereotype that immigrants and the poor bred cholera, fostering the political climate of nativism. The situation enabled then President Harrison to invoke a draconian anti-immigration policy: He simply imposed a twenty-day quarantine order blocking exposed immigrants from steerage class from embarking on American soil. That this order was

- illegal, superseding the Governor’s power to regulate health and safety of ports in his state

- it flew in the face of established medical wisdom attesting to the three-to-five day incubation period for the disease

- it targeted only the poor

- that it bankrupted steamship companies forced to pay dock fees for their ships as they waited in port

was irrelevant. Harrison’s order effectively ended immigration for five months.

New York’s governor and the local port quarantine doctor, William Jenkins, valiantly fought back – to little avail. Even though the law was on their side, the best they could do was maintain concurrent jurisdiction over immigration admittance. A year later, the Quarantine Act of 1893 codified Harrison’s actions; New York and other important ports like New Orleans would hang on to their say in regulating passengers arriving from abroad until 1921. By then, international travel and regulation of incoming passengers rested entirely in the federal government.

The steerage passengers from all three ships were taken to Swinburne Island (near Staten Island) if they were sick; the rest were taken to nearby Hoffman Island, where the conditions were reported, contemporaneously, as rankly disgusting. The wealthy, mostly non-immigrant passengers traveling First and Second class on the Normannia stayed aboard the luxury-liner until a more suitable place could house them.

Some of the more prominent aboard ship agitated to the press about the ignominy of being subjected to the same quarantine rules as the poor. Even the diagnosis of two of their class dying of cholera wouldn’t convince the privileged that they, too, were vulnerable. Cholera was a disease of the poor, of the immigrants, anyone but them. Reminders that President Polk died of the disease in 1849 – carried no weight. In the face of these rich champions of their personal liberty - science carried little weight.

With the help of New York City’s Tammany Hall politicians, Governor Flowers, an astute businessman, soon offered an alternative housing Shangri La - the Surf Hotel, a luxury vacation get-away located on Fire Island. Fronting the money from his own pocket (at a respectable interest rate), the State bought the hotel – transferred the remaining Normannia passengers to a cruise vessel to take them to Fire Island, and prepared to house them in the manner in which they were accustomed.

But the Town of Islip (under whose jurisdiction Fire Island was located) would have none of it. Fear of local transmission, fear of loss of income – the area was known for its oyster trade- should the products be boycotted, antagonism to the Democratic rule of state (Suffolk County, home of Islip, had been a Republican stronghold and supporter of Harrison) combined. The Islip Board of Health recruited a local militia and threatened the lives and safety of any passengers who embarked on their turf.

“Awaiting the Normannia passengers on the docks of Fire Island was an angry, armed mob of about 400 residents from nearby Islip, called “the Clam Diggers.” Brandishing muskets, guns, rifles, “and anything that could be charged with powder in any expectation it would explode [the] seething throng” was prepared to use any means necessary to repel the “pest ship’s” passengers from disembarking. Joining them were equally enraged residents from nearby Babylon, who threatened to destroy the docks if the cruise ship, Cepheus, tried to moor.” [1]

The Governor called out the National Guard. The standoff was temporarily abated when the locals secured a temporary injunction against the governor, claiming that local jurisdiction superseded the State’s - a similar argument Governor Flowers and Port Officer Jenkins tried against the President.

The next day the order was lifted, and the ship’s residents safely disembarked and ensconced on Fire Island. 13 days later, they were released and went home. [2]

The public health battle moves to the Courts

The public health battle had centered on the rights of the rich vs. the poor, immigrants vs. nativists, local vs. state, and science vs. liberty. Two weeks after they landed, the immediate public health crisis was declared over. The political battle died shortly after that. However, the legal battle wasn’t resolved until Feb. 1893, about the same time as the enactment of The Federal Quarantine Act of 1893, in Young v. Flowers. Paradoxically, that act gave superior rights to the federal government, circumscribing powers of the state – which still retained superior rights to control public health for its residents. Only jurisdiction over incoming ships – under the commerce clause- was to be largely transferred to the federal government.

Young v. Flowers, an obscure case limited in precedential value, provides insight into the mindset regarding issues now surfacing: the role of the locality, the state, and the federal government in pandemic times. The decision did not appear until some five months after the epidemic subsided. The court did not shy away from issuing its ruling because the matter was academic - as was asked of the US Supreme Court in recent decisions regarding state-imposed lockdown orders and which they similarly decided to tackle (See Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo).

But the ruling was hydra-headed nonetheless. While decrying that the Governor’s powers to enact precautionary epidemic regulations was limited and could not overstep objections of local entities, the court ruled that in times of a public health emergency, the powers of the governor and the port officer expanded – in the interests of protecting public health:

“Certainly, not only a regard for the lives and health of such passengers themselves, but regard for public health, required that such persons should not unnecessarily be longer subjected to the danger of contagion. The question between vessels and a landing place was a fair subject for the exercise of discretion by the health officer.” Young v. Flowers

The case might seem to support the State’s superior power in times of emergency. But a closer look reveals that our current fight between state and local governments bastardizes the time-honored expectations of the state as guardian of the public health, vested in it by the Founders.

Autonomy and liberty are crucial rights. These are governed by the Constitutions, both federal and state. The question now is not whether these rights supersede the public health – but who has the power or the right to make that determination. Governor de Santis is championing the rights of his citizens to choose. That is not the power contemplated as being supremely vested in the state under the Constitution – nor the power protected by Young v. Flowers: the police power to protect the health of the public.

[1] Barbara Pfeffer Billauer: Vaccines and Quarantines: When Law and Policy Fly in the Face of Scientific Inquiry, chapter 2. Forthcoming.

[2] See generally, Felice J. Batlan, Law in the Time of Cholera: Disease, State Power, and Quarantine Past and Future