The EPA has been busy over the last month issuing important regulations on lead:

- Significantly reduce the acceptable level of lead in dust from paint in homes after lead abatement.

- All water systems are required to replace all lead service lines (pipes) within 10 years.

Will these new rules, in practice, achieve their objectives?

Background

It has been known since the Roman period (2nd Century BC) that lead causes headaches, stomach pains, drowsiness, and convulsions at high levels. Only within the last 50 years have scientists associated lower levels of lead, previously considered safe, with behavioral problems, IQ deficits, and attention problems in children.

With that recognition, scientists have focused on removing lead from the environment (air, drinking water, paint, and food) to reduce childhood lead exposure and its adverse health effects. In the 1960s, thousands of children with lead poisoning were hospitalized in the U.S. annually, and about one in four died, while only one child died from lead poisoning from 1996 to 2006.

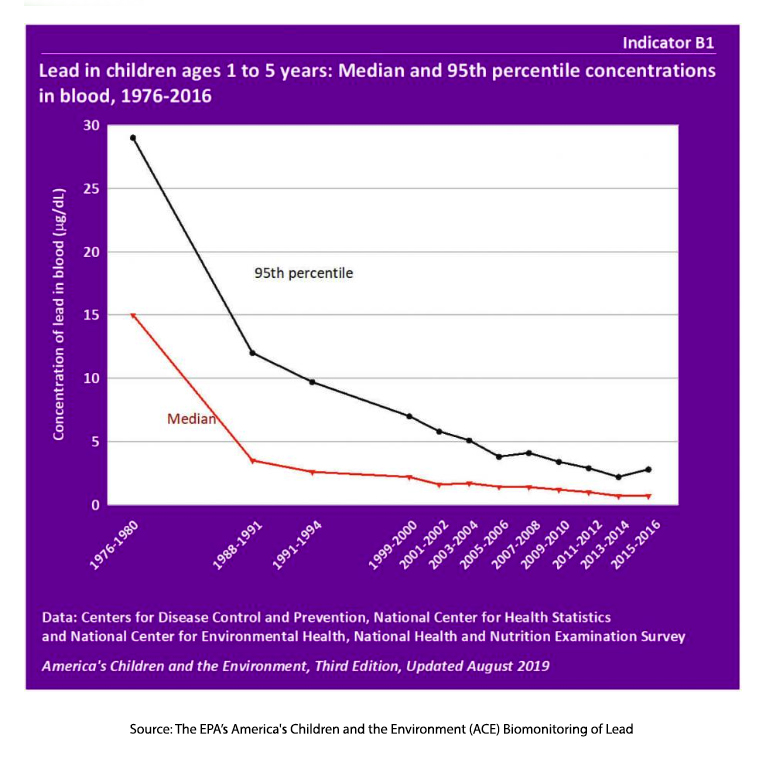

As shown in the graph, there has been a dramatic decrease in childhood blood lead levels over the years. In 1976-1980, the median blood lead level of a child aged 1-5 was 15 micrograms per deciliter. In 2016, the median blood lead level was reduced to 1 microgram per deciliter, with the percentage of children aged 1-5 with blood lead levels less than or equal to 5 micrograms per deciliter declining more than ten-fold. Most of this decline is due to the removal of lead from gasoline in 1996.

As shown in the graph, there has been a dramatic decrease in childhood blood lead levels over the years. In 1976-1980, the median blood lead level of a child aged 1-5 was 15 micrograms per deciliter. In 2016, the median blood lead level was reduced to 1 microgram per deciliter, with the percentage of children aged 1-5 with blood lead levels less than or equal to 5 micrograms per deciliter declining more than ten-fold. Most of this decline is due to the removal of lead from gasoline in 1996.

This has been a great success story, considered by the CDC as one of the ten great U.S. public health achievements.

Lead in Paint

As discussed in my article Lead: Progress But Still a Problem, lead in paint chips or dust is a significant source of lead exposure in young children today, resulting when lead-based paint deteriorates or is disturbed or when children ingest lead chips resulting from peeling paint.

Lead was first added to paint in the early 1900s and in 1978, the federal government prohibited lead-based paint in residences. However, it is estimated that 31 million pre-1978 houses still contain lead-based paint, and 3.8 million of them have one or more children under six living there.

On October 24, 2024, the EPA finalized new regulations reducing the level of lead in dust from paint, which is considered hazardous, lowering the standards for the allowable lead levels in floors, windowsills, and window troughs. [1] The regulations do not compel property owners or residents to take immediate action, but the EPA’s regulation must be met if a lead-based paint activity, including measures designed to permanently eliminate lead-based paint hazards, is performed or if a child living in the home has a high lead level. The rule is estimated to cost $207 million to $348 million per year and is expected to accrue to landlords, owners, and operators of child-care facilities, residential remodelers, and abatement firms.

Lead in Drinking Water

Lead service lines were allowed in the U.S. until 1986, when Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act, prohibiting the installation of new lead pipes in public water systems. However, this rule did not apply to existing lead pipes, and an estimated 9.2 million lead service lines are supplying water to homes today.

Over the years, it became increasingly clear that lead pipes could contribute to the levels of lead reaching drinking water in homes after the water was treated at the water treatment plants due to the corrosion of pipes, consisting of chemical reactions between the water flowing through the pipes and the lead.

The EPA’s key regulations on lead, the Lead and Copper Rule initiated in 1991, required large water systems to begin corrosion control and take action in the presence of high lead levels. The Lead and Copper Rule Revisions of 2021 required an “inventory” of lead service lines and a plan to replace them. The Lead and Copper Improvement Act now requires all lead service lines to be replaced within 10 years and lowered the “action level” from 15 to 10 ppb (parts per billion).

The EPA’s estimated cost is between $1.5 and $2 billion annually [2], although estimates by counties are roughly double that at $3 to $4.9 billion annually. The American Water Works Association (AWWA) estimates it costs about $10,000 to remove each lead service line, costing over $90 billion (estimating 9 million lead service lines in the U.S.).

Impact of the Rules

In an ideal world, one would like to remove all lead service lines and get dust from lead paint as low as possible. However, this ideal runs into serious cost considerations. The lead paint rule may discourage lead abatement in homes because of the increased cost. It could also have negative consequences for the availability of child-care centers and apartments:

“[The EPA rule may] ultimately reduce the availability and affordability of rental housing for families with children.”

- Nicole Upano, assistant vice president of the National Apartment Association

“We are concerned that most, if not all, regulated systems will not have the resources needed to meet EPA’s ambitious timeline for lead service line removals. We are also concerned with the potential impacts on households that cannot afford higher water bills, as increased compliance costs are directly passed on to customers in many cases.”

There is $15 billion in federal funding available over five years for removing lead service lines under the bipartisan Infrastructure Law. $9 billion has been spent so far, replacing about 1.7 million lead pipes, and the administration has just announced an additional $2.6 billion for lead service line replacement. There is also $35 million in competitive grant funding. This results in $8.6 billion available for lead service line replacement, far less than the AWWA’s estimate of $90 billion.

I believe that federal funding will ultimately decline before water systems can complete their lead service line replacements. Water and utility bills are already increasing, and even with government assistance, the impact on households will be meaningful. EPA should move to a targeted approach focused on the water systems that most need replacing their lead service lines. A blanket approach may sound good, but it is unlikely to achieve its desired effect.

The EPA says this rule is all about the children. We all love kids, but a targeted approach to lead removal will have the most impact in the real world.

[1] The allowable levels were reduced from 10 micrograms per square feet (µg/ft2) to 5 µg/ft2 for floors, 100 µg/ft2 to 40 µg/ft2 for windowsills, and 400 µg/ft2 to 100 µg/ft2 for window troughs