This is a brief excerpt. See the full article here.

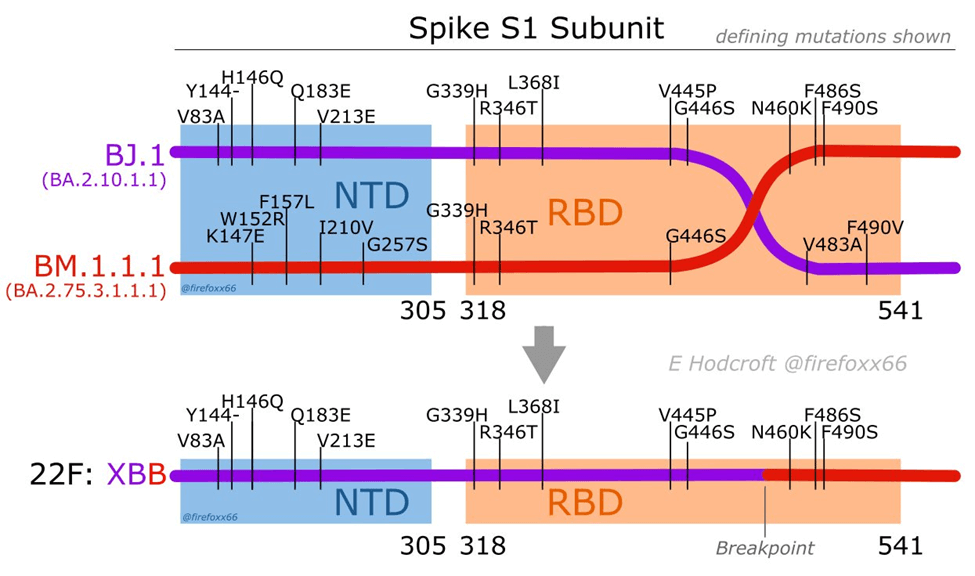

The most striking thing about XBB.1.5 is that it didn’t simply arise as the result of point mutations in the RNA; rather it is the result of a recombination of two descendants of the BA.2 variant. Swiss virologist Dr. Emma Hodcroft has made a useful diagram that illustrates what that means:

Credit: Dr. Emma Hodcroft

It might look complicated, but in the upper part of the figure, we need only focus on the horizontal purple and red lines, which represent the RNAs that comprise the genome of two discrete subvariants of the BA.2 variant before recombination occurred. The bottom part of the figure depicts the genome of the new virus, XBB, that resulted from recombination (that is, breakage and reattachment, or what Dr. Hodcroft calls “template switching”). XBB is comprised of genetic material from both of the “parents,” which is shown by the line being both purple and red, joined at the “breakpoint.”

Dr. Hodcroft described the process this way:

When a virus copies itself, it can ‘template switch’ between different genomes floating around. If those are all the same, the end product isn’t different! But if distinct lineages are there at the same time, we can spot these ‘chimera’ children – recombinants!

This is somewhat similar to what happens when an animal is infected by two different flu viruses. Inside the animal, they exchange RNA fragments to create a new, more dangerous virus which goes on to spread.

Lowering the probability

The important takeaway: For the recombination event to have occurred, the two parental viruses must both have infected a person and have been present in the same cell simultaneously for enzymes to have broken and reattached portions of the two genomes.

That scientific observation has important implications for public policy: To lower the likelihood of more dangerous subvariants arising in this way, we should strive to lower the probability of such co-infection events. We do that by decreasing the number of infections that occur, and we do that by applying the old 2020 rallying cry: “Flatten the curve.”