There is a lot to unpack here, so this article will focus on the first of those questions – can food be addictive in  the same way we talk about addiction to drugs like cocaine or fentanyl. [1] Cameron wrote about food addictions more generally a week ago if you are looking for more background.

the same way we talk about addiction to drugs like cocaine or fentanyl. [1] Cameron wrote about food addictions more generally a week ago if you are looking for more background.

The Addictions

Many in the media use the term addiction to refer to both chemical and behavioral problems. Mental health experts continue to struggle with the definitions. While there are marked similarities between drug abuse and overeating, the evidence suggests that people who display symptoms of food addiction aren’t hooked on potato chips or ice cream. Instead, they are afflicted by a behavioral disorder and should be treated as such.

Chemical addiction

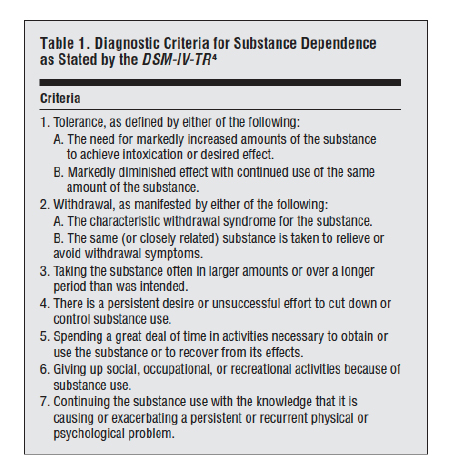

Here are the criteria associated with the diagnosis of chemical dependence.

Food checks off many of the boxes. The one exception would be the first, tolerance.

Food checks off many of the boxes. The one exception would be the first, tolerance.

When eating a meal, we quickly develop a diminishing experience of taste. Think about the difference you experienced in that first “mouth-watering” bite compared to the 20th. Of course, our taste experience does return to its non-attenuated level with the next meal. And it is unclear whether food requires increasing levels to achieve the desired effect or satiation.

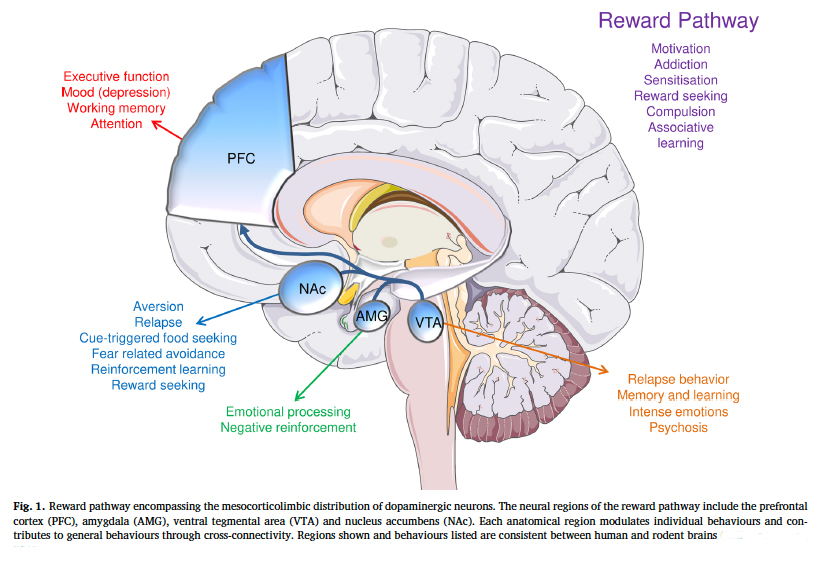

That being said, food has many similarities to drugs of abuse in our higher processing centers within the brain. The diagram is taken from a study on sugar consumption and addictive behaviors. [2]

These are the same areas involving dopaminergic neurons that fire in response to drugs of addiction. That should be no surprise, these are reward pathways, and addictive drugs provide a transient reward to some individuals.

These are the same areas involving dopaminergic neurons that fire in response to drugs of addiction. That should be no surprise, these are reward pathways, and addictive drugs provide a transient reward to some individuals.

Drugs of abuse have very similar pharmacokinetics, the rate at which they are absorbed into our bloodstream, how long they persist and how quickly they are detoxified and removed. In general, drugs of abuse are rapidly absorbed, creating the “rush,” the “high,” and then rapidly the “crash.” Food does not have the same pharmacokinetics except for one component, sugar.

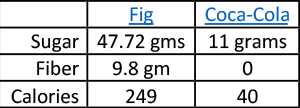

Foods containing high levels of refined sugar may mimic those addictive pharmacokinetics. Any parent will attest to the “sugar rush” a child experiences after eating candy. But food is something more than the total of its components. Let’s consider what many of us would consider healthful, a dried fig, and compare it with a villain, the sugar-sweetened beverage Coca-Cola. We are talking about 100 gm, roughly 3 ounces, in both instances. As it turns out, the fig has far more sugar and calories. The difference between the sugar-rush of Coca-Cola and the “nutritional benefit” of the dried fig lies in the fiber. Fiber slows the release of those sugars into our bloodstream, altering the pharmacokinetics of the fig’s sugar. No one claims figs are addictive.

Foods containing high levels of refined sugar may mimic those addictive pharmacokinetics. Any parent will attest to the “sugar rush” a child experiences after eating candy. But food is something more than the total of its components. Let’s consider what many of us would consider healthful, a dried fig, and compare it with a villain, the sugar-sweetened beverage Coca-Cola. We are talking about 100 gm, roughly 3 ounces, in both instances. As it turns out, the fig has far more sugar and calories. The difference between the sugar-rush of Coca-Cola and the “nutritional benefit” of the dried fig lies in the fiber. Fiber slows the release of those sugars into our bloodstream, altering the pharmacokinetics of the fig’s sugar. No one claims figs are addictive.

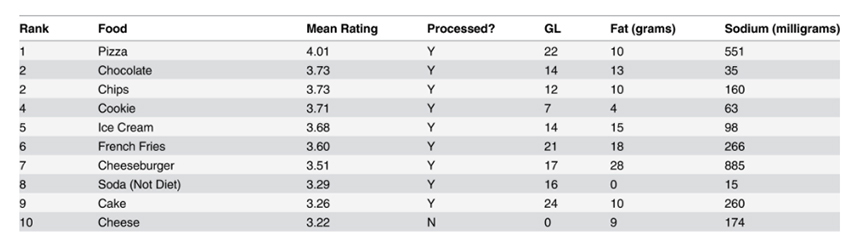

Consider this study [3] of foods people struggled to eat in moderation. The participants underwent the Yale Food Addiction Survey, a standard instrument to measure “addictive-like eating.” They were then asked to identify foods that were difficult to resist. The foods were categorized as high in both fats and refined carbohydrates, high in fats alone, high in carbohydrates alone, and low in both fat and refined carbohydrates. Here are the top 10:

A few words of explanation. The researchers defined processed foods as items high in both fat and carbohydrate. But would you use the word “processed” to describe the number one culprit, pizza? It is nothing more than flour, water, salt, yeast, tomatoes, and cheese. The critical column is GL, which stands for glycemic load. Our nutritional labels tell us the amount of sugar in a product. But as we have seen in the example of the dried fig, we need to know whether sugar is accompanied by other nutrients that alter its pharmacokinetics. The term used in that instance is the glycemic index, which describes how quickly sugar enters the bloodstream; a higher glycemic index indicates faster absorption. Coca-cola has a glycemic index of 63; that nutritious dried fig sits at 61.

The researchers categorized refined carbohydrates based on their glycemic load (GL), which “captures not only the dose of refined carbohydrates but also the rate at which they are absorbed in the system.” The researchers have identified an important distinction that characterizes the sugar rush, high, and crash. GL differs from the glycemic index, accounting for the amount of sugar in the meal along with its pharmacokinetics or bio-availability. If you look at the column with GL values, they are all over the place, but a higher GL seems to correlate with problematic foods. The glycemic load combines the pharmacokinetic information of the glycemic index with the nutritional information of the amount of sugar present in the food.

Based on this information, we can say that sugar is similar to drugs of addiction in its absorption, utilization, and breakdown. Still, we cannot conclude that sugar is a chemically addictive substance. There is a better case to be made for eating addiction as a behavioral issue than for food addiction as a substance use disorder.

Behavioral addictions

In the early part of this century, the similarity between the behavior of those with chemical addictions and those

“not addicted to a substance but the behavior or the feeling brought about by the relevant action," became more apparent. A diagnosis of behavioral addiction was developed and entered into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Only two behaviors have been identified as meeting the criteria for behavioral addiction, gambling and Internet gaming.

Here are those criteria

- Salience: Domination of a person's life by the activity

- Euphoria: A ‘buzz’ or a ‘high’ is derived from the activity

- Tolerance: The activity has to be undertaken progressively to achieve the same ‘buzz.’

- Withdrawal Symptoms: Cessation of the activity leads to the occurrence of unpleasant emotions or physical effects

- Conflict: The activity leads to conflict with others or self-conflict

- Relapse and Reinstatement: Resumption of the activity with the same vigor subsequent to attempts to abstain, negative life consequences, and negligence of job, educational, or career opportunities. [4]

Food can check off all the boxes here, but one. Yo-yo dieting attests to the fact that some individuals resume “the activity with the same vigor subsequent to attempts to abstain,” despite negative life consequences. But no one I know neglects their job, education, and career to eat. Or do they?

Researchers have identified a subset of behavioral addiction that they term process addiction – where the addiction lies in the ritual of eating rather than the food itself. Of course, this raises another interesting term to differentiate, habit. We can separate ritual and habit relatively easily with this phrase; some eat to live (habit), while others live to eat (ritual).

The distinction between habit and addiction is more ambiguous in the behavioral arena. The example here might be our “comfort” food – when having a meal brings about a sense of comfort and security, a meal we turn to when we are anxious or depressed. At what point in reaching for my comfort food do I have an addiction to the ritual of this meal? A review of comfort foods [5] found that they were often eaten in response to feeling down or out-of-sorts and that eating them lifted one’s spirits. That would suggest positive feedback between behavior and mood. But the review also pointed out that

“…what constitutes comfort food differs widely from one individual to the next, and from one culture to another…. generally-speaking, comfort foods are not characterized as tasting especially good, nor are they characterized by their ‘healthfulness.’ And nor, for that matter, do there appear to be any specific sensory characteristics that help to distinguish comfort from other classes of food.

Indeed, given the wide variety of different foods that people describe as comforting to them, it would seem unlikely that there are going to be any particular components (i.e., specific nutrients or tastes) that one can point to as having a physiological impact on whoever is consuming them. Rather, it would seem that certain foods take on their role as comfort food through association with positive social encounters in an individual's past.”

[1] You can find a copy of the Newsweek article here

[2] The impact of sugar consumption on stress driven, emotional and addictive Behaviors Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.05.021

[3] PLOS Which Foods May Be Addictive? The Roles of Processing, Fat Content, and Glycemic Load DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117959

[5] Comfort food: A review International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science DOI: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2017.07.001