Findings of Naval Inquiry and National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB)

While the distinguished visitors – members of Congress who sat on committees that appropriated funds to the Navy, and their families, were not at fault they may have contributed to the environment aboard the USS Greeneville that lead to the accident. They had come for a bit of a show, and the officers obliged. Perhaps the prolonged luncheons with the Captain and Executive officer might have been shortened – how many photographs do you really need to autograph?

“He indicated that if he had felt rushed, he would not have continued to sign souvenir photographs in his stateroom.”

In any event, the nuclear submarine was running late to return to port, and they had yet to demonstrate TO THEIR GUESTS? surfacing and diving – the naval equivalent to a roller coaster ride. The visit was out of sequence with the plans for the submarine that had training to accomplish, were they training or entertaining - maybe the crew thought this was simply a “pleasure outing.”

“They [the crew] either adopted a somewhat informal attitude toward their duties or concentrated on accommodating the visitors to the detriment of their work.”

At the same time, the Greeneville was experiencing some equipment problems. The displays indicating the ships positioning in relation to other objects around them or on the surface were not fully communicating with one another. The Navy had known this could be a problem, especially in times of war aboard a warship, so there were protocols in place on how to share the information quickly and correctly – “Roger that.”

“Problems were exacerbated when the CO did not use all his resources to correctly assess the current operating situation….”

Then, of course, there are assumptions. Here is the NTSB narrative,

“Before the Greeneville rose to periscope depth, the CO [commanding officer] announced to everyone in the control room that he had a “good feeling” for the contacts [possible vessels on the surface], which had the effect of discouraging backup from his crew. The inexperienced [officer on deck] acquiesced to the more experienced commanding officer...

The CO continued to rush, pushing his crew and truncating recommended steps for safe operation. While at periscope depth, he interrupted the [officer on deck] periscope sweep and took over operating the periscope, executing only a few brief sweeps in the general area where he believed the sonar contacts to be. … He did not order the submarine to a shallower depth for a significantly better height of eye and he did not execute a slower, more deliberate sweep to ensure that no vessels were obscured by the haze. Once again, he did not use his crew resources and solicit the feedback or assistance necessary for safety.”

And like all human organizations, the USS Greeneville had a culture – guided by naval protocols, enforced by training and modified by the experience and interactions of the crew and command staff.

“…because of his [the captain’s]rank and the respect among the crew that he commanded, his crew appeared to have acted as though they. . . if the captain thinks it ís okay to go up, who am I to stand in front of him and tell him it ís not right, and they kind of just rolled on the captain’s decision to go up. If crewmembers disagreed with the CO’s assessment, none spoke up to provide him essential feedback, particularly in the presence of the visitors.”

In the final moments before the still-avoidable collision, the captain decided to do an emergency surfacing. It was part of their training program and would be a good test of the crew’s preparedness coming as a surprise. It would also be quite a show for the visitors. With little uncertainty, a rush to perform and get home, the captain gave the orders for an Emergency Ballast Blow, forcing pressurized air into the ballast tanks and quickly making the submarine very buoyant and quickly heading for the surface. And the underbelly of the Ehime Maru.

In the final moments before the still-avoidable collision, the captain decided to do an emergency surfacing. It was part of their training program and would be a good test of the crew’s preparedness coming as a surprise. It would also be quite a show for the visitors. With little uncertainty, a rush to perform and get home, the captain gave the orders for an Emergency Ballast Blow, forcing pressurized air into the ballast tanks and quickly making the submarine very buoyant and quickly heading for the surface. And the underbelly of the Ehime Maru.

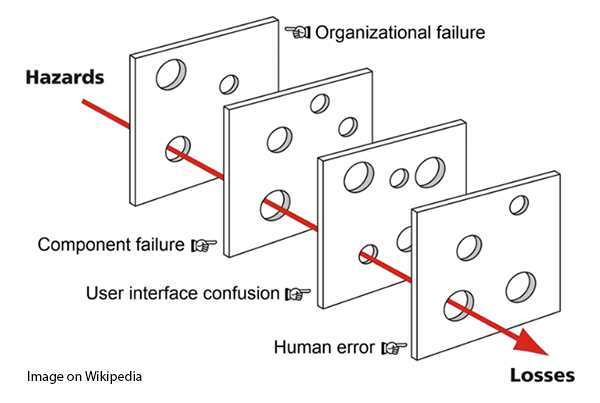

What about the Swiss Cheese?

The Swiss Cheese, in this case, refers to a concept in risk management – that no one event is the cause of a bad outcome or disaster. Each event is like the hole in Swiss Cheese; each precaution is the slice itself. If you line [UP?] many slices of Swiss cheese, it is unlikely that all the holes will line up.

The Swiss Cheese, in this case, refers to a concept in risk management – that no one event is the cause of a bad outcome or disaster. Each event is like the hole in Swiss Cheese; each precaution is the slice itself. If you line [UP?] many slices of Swiss cheese, it is unlikely that all the holes will line up.

The collision between the USS Greeneville and the Ehime Maru was a textbook example of this concept. Look at all the events necessary for that disaster to occur and how many precautions were ignored or subverted. If only the cruise hadn’t been rushed, there were no visitors, or the surface contact instrumentation was working correctly – any or all could have prevented the loss of life.

It’s all there, component failure, confusion, and human error. And that brings us to our final connection.

Swiss cheese and COVID-19.

We can, and have, spent a great deal of time, ink, and bytes discussing the failure of the US response to COVID-19. I will leave all of that, including the divisive and detrimental name-calling of opponents, aside. Instead, let's deal in the present with how we are best to reduce COVID-19 infections. We have many slices of cheese at our disposal – you already know what they are. There is vaccination, social distancing, and masking, to mention the big three. There is also quarantine, business closure, immunization passports, restricted travel, or if you are so inclined, hope and prayer. As the USS Greeneville so clearly demonstrates, you need many precautions, not one or two.

As a physician, vaccination and social distancing are, in my opinion, the most effective, easily performed precautions. As a surgeon, who wore a mask every day of his professional life, for three or four hours at a time, without any breathing problems, without infecting myself, I can do masks if requested. I would add that in the times when I inadvertently walked into the operating room without a mask, and the circulating nurse called me out because there were “open sterile instruments.” I apologized, turned around, and got a mask. I didn’t claim special privilege or feel that my rights were being trampled upon – that was what you did as part of the team, even when you were the “team leader.”

In the real world, the vaccines we are using now, not in the study, remain very effective, but not completely. There will be increasing numbers of “breakthrough” infections; if, by breakthrough, you thought that the vaccine was 100% effective. No one thing is the underlying cause or preventative; remember the Ehime Maru. Breakthrough infections greatly reduce your chance of becoming significantly ill or dying; they greatly reduce but do not eliminate the possibility of transmission. If you are looking for a fact, there it is. To prevent a disaster, we need to add more slices of Swiss cheese to our system; that is why masks may once again be helpful, just like prudent social distancing.

Our government has only crude tools to apply in these public health situations, mandates, and enforced rules. Individuals can be more strategic, wearing a mask when surrounded by strangers, getting vaccinated on the down-low to avoid a social confrontation, skipping the night out, and instead, party with your pandemic pod.

Sources: The Collision Of Us Submarine Greeneville And The Fishing Vessel Ehime Maru – Investigation Report