The two studies published in JAMA Network Open looked at advertising exposure of children to food products and adults to tobacco on screens. Both have some interesting insights to consider.

Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising

The study utilized data from the Nielsen Company on children aged 2 to 5 and 6 to 11 years who viewed a particular program on broadcast, cable, or syndicated “television” screens. The foods of concern included beverages, cereal, snacks, sweets, other foods (such as fruits, vegetables, meats, pasta, condiments), and fast-food and full-service restaurants. Nutritional assessment followed guidelines from the Federal Trade Commission, CDC, FDA, and USDA to identify foods that should not be marketed to children.

Between 2013 and 2022:

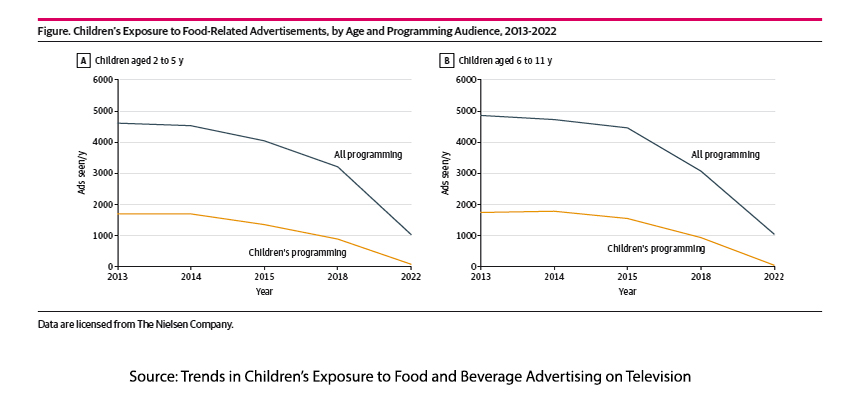

Exposure to food-related TV advertisements decreased by 77.6% (from 4611 to 1035 ads per year) for children aged 2-5 years and by 78.5% (from 4860 to 1046 ads per year) for those aged 6-11 years. The most significant decreases were in cereal advertisements, the smallest for fast-food restaurants, although both were greater than 60%. While sugar-sweetened beverages were slightly more advertised than those not, the decrease here was roughly 74% for both age groups. More importantly, these decreases were dramatically more significant for programming designated for children – where > 35% of the audience is aged 2-11.

- 95.1% decrease in exposure (from 1703 to 84 ads per year) for children aged 2-5; 97% decrease in exposure (from 1745 to 52 ads per year) for those aged 6-11.

- Less than 10% of the total food-related ad exposure came from children’s programming, and the majority of exposure came from non-children’s programming, regardless of the percentage of children (≥20% or ≥35%) used to define children’s programs.

The vertical legend does not clearly indicate the exposure in 2022; it was essentially 100 or fewer ads for each group—quite a reduction; however, according to the researchers, not enough.

“…young children continue to view more than 1000 food-related advertisements per year, similar to their 6- to 11-year-old counterparts. Government regulations that restrict advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages applied to programming based on time of day rather than on child-audience share would be more effective. In addition, the finding that the nutritional content of foods and beverages that continue to be advertised, … do not meet the IWG nutrition criteria supports the WHO recommendation for government-led criteria to limit foods and beverages marketed to children.”

As with many studies, the social construct of race, was used as an additional "lens" to analyze the problem. Black children watched screens 25% to 62% more than their White peers but were exposed to proportionally more food ads. Why might that be? Here is where the insight can be found. The study considers screen time across a range of sources. While as a Boomer, the only kids' TV I saw was on regular channels. Today, cable channels cater directly to children, along with a host of YouTube and other Internet sources.

My grandchild has exposed me to Bluey, Disney, and now Puffin Rock, and I must say there is no advertising on these cable programs. So perhaps rather than another government regulation we might ask the parents to control the programming. And yes, I understand that not everyone has the financial wherewithal to purchase cable, or they find the screen a less expensive babysitting option. But is there a minimal degree of parental responsibility to be exercised? And if we need to further regulate, those rules should to be applied in some fashion to child-directed “influencers,” a majority of whom feature food in their YouTube videos.

Tobacco and Screens

The second study looks at exposure to tobacco ads on television and the less-studied streaming platforms. The data was derived from the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS 6), asking for “self-reported exposure to tobacco advertisement, marketing, or promotion on TV or streaming platforms.” In a sample of 5800 respondents, the estimated exposure to tobacco was 12.4%. The researchers further stratified the data to show higher exposure among:

- Individuals aged 35 to 49 years (13.4%)

- Those with a high school education or less (16.4%)

- Non-Hispanic Black or African American respondents (19.4%)

- Individuals with a household income less than $20,000 (17.6%)

- Current smokers (17.0%)

The researchers conclude:

“Study findings call for regulation in the TV and streaming space, given its potential for exploitation. As these platforms continue to dominate the entertainment landscape, it becomes increasingly important to regulate content that may contribute to detrimental health outcomes associated with smoking.”

There has been a ban on tobacco advertising on TV since 1970, and streaming services do not have tobacco advertising either. So, in addition to admitting that the question they asked regarding” advertisement, marketing, or promotion” is subjective, they go on to state that

“most reported exposures are likely due to tobacco use depictions in shows and movies. This type of promotion is difficult to regulate, as it is unclear whether tobacco companies fund such depictions or are artistic choices by content developers.”

The researchers are not alone in a desire to further regulate the content of our screens. The Truth Initiative, initially funded by the Tobacco Master Settlement and “the largest non-profit public health organization committed to preventing youth and young adult nicotine addiction,” writes,

“On-screen smoking, which is often glamorized and portrayed as edgy and cool, is rising despite well-established research that it influences young people to start using tobacco products. While the youth smoking rate is low, peer-reviewed research from Truth Initiative demonstrates that exposure to smoking imagery in streaming shows can triple a young person’s odds of starting to use e-cigarettes – today’s top tobacco product among young people. This association between tobacco imagery and tobacco product initiation builds on long-established research confirming that exposure to smoking in movies leads young people to start smoking.” [emphasis added]

It is undoubtedly true that the sources of our entertainment and news have shifted over the past few years. It is equally true that we are influenced by advertising and the content of our screens. But in both the case of foo (children) and tobacco (adults), the individuals identifying harm seem to feel that until these exposures are entirely prohibited, our efforts are insufficient. What are the responsibilities and roles of parents in either instance? Where is the line where we cross over to the Nanny State?

In the endless debate over advertising and its influence, the real question is whether we're ready to admit that maybe, just maybe, some of this responsibility lies closer to home. While researchers and public health advocates demand more regulation, it might be time for parents to step up, change the channel, or maybe—just maybe—talk to their kids about healthy choices. And for the adults, if you're getting seduced by tobacco in a Netflix binge, well, maybe there's a bigger problem than just what's on your screen.

Sources: Trends in Children’s Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.29671

Disparities in Exposure to Tobacco on Television or Streaming Platforms JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27781