“No one should go bankrupt just because they had the misfortune of becoming sick or hurt.”

-Vice President Harris, Stat

As Stat reports, forgiving medical debt is a plank in the Democratic Party platform. Depending on your data, this debt ranges from $20 to $220 billion. Let’s examine the data for ourselves.

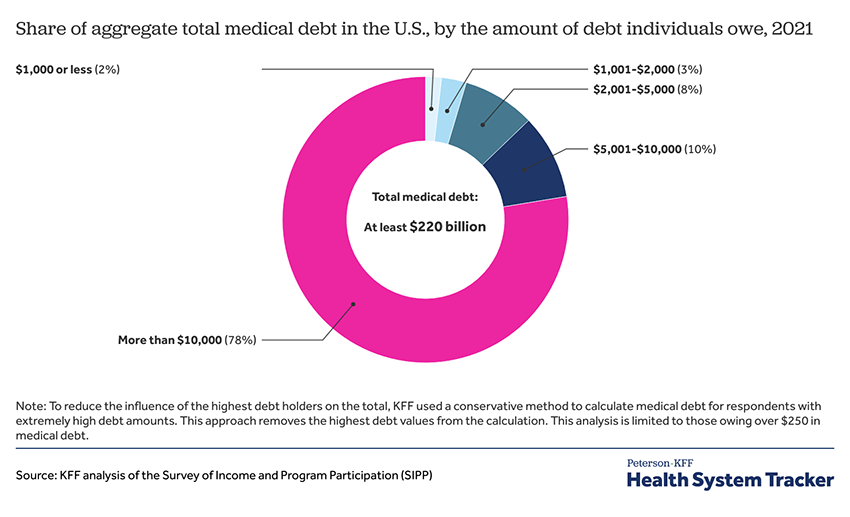

That $220 billion comes from a study undertaken by the Kaiser Family Foundation analyzing data from a nationally representative longitudinal survey by the US Census Bureau, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). People aged 18 or older were asked “whether they owe any money for medical bills not paid as of December 2021.”

- >90% of Americans have some form of health insurance.

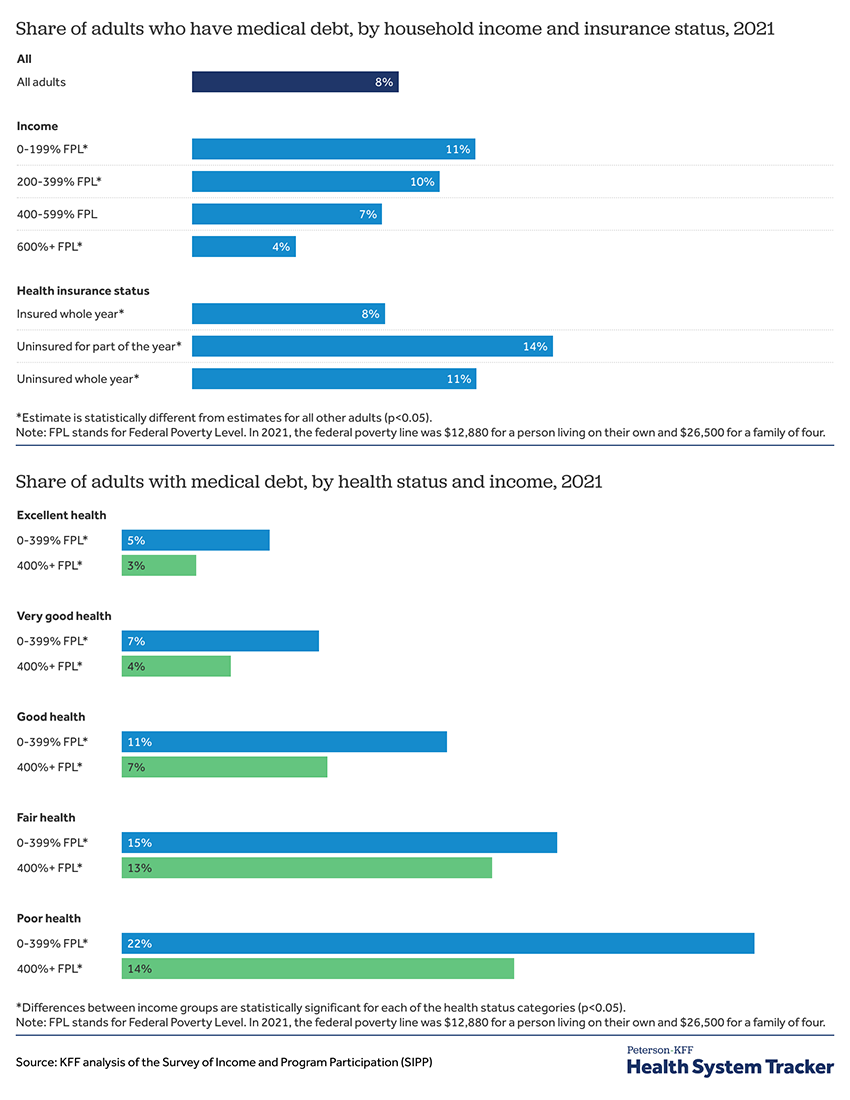

- 15% of American households, roughly 20 million of us, owed medical debt in 2021, which includes co-payments, deductibles, out-of-network coverage, surprise billing [1], and payments for those without insurance. That percentage rises to 41% if credit card medical debt or family loans are included.

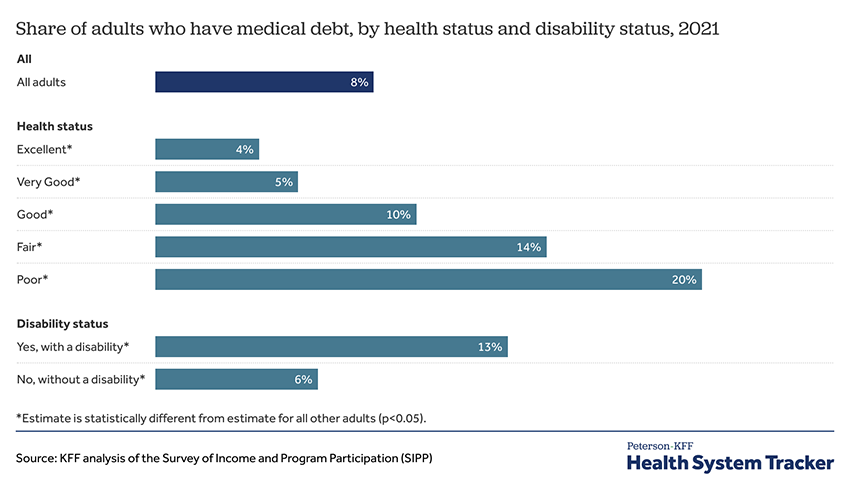

As you would anticipate, medical debt closely follows your physical and fiscal health.

- Peak medical debt by age involves those 35 to 64 who carry 21% of the total debt. That percentage drops 4-fold to 6% in the over 65’s who have the greatest health costs. (That far lower debt is among the strongest arguments for Medicare-for-all).

- Medical debt among that age demographic is more pronounced for those without insurance in any form. The individuals asked to pay “sticker price,” the amount physicians and healthcare systems charge before the essentially universal write-downs driven by Medicare’s fee schedule and commercial insurers.

- As you would anticipate, medical debt is entangled with both income and health status

- Roughly 75% of that debt is $5,000 or less, with the median between $2-5,000. But that remaining 25% contributes more than 75% to that total $220 billion.

According to a study by the Urban Institute, the bulk of that $5,000 or more debt is owed to hospitals.

- A collection agency contacted 60% of those patients; 12% were sued had wages garnished or bank accounts taken.

- One-third worked out a payment plan without discounts, 21% received discounted bills, and 6% offered help applying for Medicaid. (That partially explains why those with insurance for part of the year owe more than those without insurance over the year.)

There is no fiscally sound way that we will write off $220 billion in unpaid medical debt while making those owed money “whole.” But that doesn’t mean other solutions are available.

Let us begin with a better understanding of the role of collection agencies. They are assigned patient accounts in arrears and receive a percentage of the monies they collect. The hospital, acting through the collection agency, accepts a deeply discounted payment to close the account, typically 20 to 40%. As those accounts age, collection is more difficult, and that discount grows. NY City has teamed with a non-profit that purchases medical debt so that the $2 billion the mayor has earmarked for resolution will cost the city considerably less.

Another solution lies in the non-profit status of many health systems. As I have said before, non-profit is a tax status, not a description of net profit. These non-profit hospitals avoid taxation by paying upwards of 15% of their expenses as community benefit. Currently, around half of that benefit goes toward canceling medical debt. Some of that debt is forgiven, and in other instances, the hospital, through financial aid, pays itself, and in other cases, that debt forgiveness absorbs “losses from Medicaid” that are not as fiscally real as hospitals would like us to believe. As a study in JAMA, reported by Stat pointed out,

“Tax exemption provides no assurance that these hospitals will behave in accordance with their charitable mission, and gives them an unfair competitive advantage against for-profit hospitals. If non-profit hospitals are unwilling to provide sufficient community benefit to justify the value of their current tax exemptions, local communities should not be deprived of the property tax revenues that allow them to fund local schools, parks, and other public services.”

If Congress had the will, it could more strongly tie tax advantages to paying down medical debt. If not, the tax revenue that could accrue could be used to pay down that debt. Still, if you think more carefully, you realize that in both instances, the money comes from the hospitals and health systems, in one instance as an accounting and in another washed through our tax system. Given the proclivities of our legislators, it may be safer to ask the hospital to write off debt with accounting rather than taxes.

Of course, some will argue that we should not forgive the debt at all. This seems to be needlessly cruel for those at the lower end of the income spectrum, although I can already hear the argument that their bad health comes from their bad habits and shouldn’t be “rewarded” with debt relief. But finding a way to forgive medical debt will give a boost to those low- and middle-income families who put in a full week’s work and have commercial insurance that is inexpensively provided because it features high deductibles and co-payments. Of course, an even better solution would be to fund our health care so that debt is not an issue – that remains an aspirational goal.

In a nation where healthcare is a game of financial Russian roulette, medical debt isn't just a burden—it's a feature. Until we figure out how to stop punishing people for getting sick, we’ll keep spinning the wheel, hoping to avoid the bankruptcy slot.

[1] Surprise billing is a bill for medical services from a provider or facility that your insurance plan doesn't consider in-network. This can happen when an emergency or care at an in-network facility involves an out-of-network provider. Congress passed a No Surprise Act to stop the practice, but those ever-resourceful commercial payers have found loopholes in the law.