Kidney failure, also known as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is life-ending, requiring kidney transplantation or dialysis. Dialysis is a process that removes toxins and excess fluid from the blood, replacing the kidney’s function. Dialysis involves filtering the blood through a membrane, allowing the forces generated by differences in concentration (osmotic pressure) to move the metabolites and excess fluid out of the body. Hemodialysis involves filtering the blood through an external membrane and typically involves thrice-weekly 3-4 hour treatments. Peritoneal dialysis consists of placing the “cleansing” fluid into your abdominal cavity (peritoneum) and letting the natural membranes of that body cavity filter the blood. It is far slower than hemodialysis, necessitating 10 hours daily.

Both methods are disruptive in their own way. Hemodialysis seems shorter but ties an individual to sitting in a chair for 4 hours or so and often results in a “blah” post-dialysis feeling, meaning that 3 days a week are lost to care. Peritoneal dialysis can frequently be done while sleeping, which allows patients more daytime mobility. It is also a bit more portable than hemodialysis, making travel more accessible. Both have similar problems with infections and maintaining access to the bloodstream or peritoneum. The federal government has paid the cost of care for individuals with ESRD for 51 years; it is our oldest form of nationalized healthcare.

Over 800,000 people have ESRD, and most are treated with in-center dialysis. 14% can accomplish their dialysis at home. Black, Hispanic, and low-income patients are more often treated in-center, creating disparities in care. To address this disparity, CMS launched the End-Stage Renal Disease Treatment Choices (ETC) model in 2021, a carrot-and-stick financial model aimed at increasing the use of home dialysis, kidney transplants, and transplant wait-listing among Medicare beneficiaries. The model included mandatory participation from 30% of the nation's hospital referral regions (HRRs), with performance-based payment incentives and penalties for facilities and clinicians.

A new study in JAMA Open Network reports on the results after two years of implementation. The data comes from CMS claims and enrollment information and data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). While CMS attempted to randomize the hospital referral regions to the control or intervention arms, there were differences that persisted throughout the 2 years, including:

- 4% lower prevalence of peritoneal dialysis treatment

- Similar likelihood to offer peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis training

- Similar social worker staffing

- A higher proportion of non-Hispanic Black patients

- Lower proportion of Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Asian American patients

- Similar numbers of dual eligible beneficiaries (With Medicare and Medicaid insurance)

- 4% greater likelihood of receiving pre-kidney failure nephrology care

- Lower median household incomes

- Overrepresentation of Southern and Northern US regions

- Underrepresentation of Midwest and Western regions

After two years of financial carrots and sticks, there was no improvement in home dialysis or transplantation rates. My colleague, Dr. Henry Miller, has written about the problems with UNOS and organ transplantation. I will concentrate on looking a bit more at home dialysis.

After two years of financial carrots and sticks, there was no improvement in home dialysis or transplantation rates. My colleague, Dr. Henry Miller, has written about the problems with UNOS and organ transplantation. I will concentrate on looking a bit more at home dialysis.

This is the second study of the ETC program. The report on the first year offered some mixed results, suggesting that an improvement in transplantation and home dialysis rates would rise over time. The second year seems to dash that hope, although as Stat reports, CMS wants to keep hope alive.

“Given the challenges and the complexity of increasing home dialysis and transplant rates, it is early to form conclusions about possible longer-term impacts of the model during the early years of the model implementation.”

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul

What was true in the first year was that

“dialysis facilities serving higher proportions of patients with social risk features had lower performance scores and experienced markedly higher receipt of financial penalties.”

In other words, the incentive penalty program created financial harm. The second year saw no improvement, and one of the salient reasons offered by the authors is that the bulk of these dialysis centers, in both the treatment and control arms, are controlled by two companies, so incentive payments offset penalties. Carrot and stick policies don’t work when Peter and Paul are in the same company.

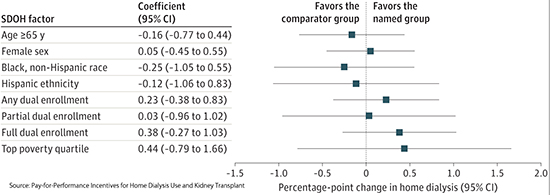

The authors go on to point out that none of the social determinants of health that they considered impacted the rates of home dialysis. But this is really because they were, like the drunk looking for their keys, looking in the wrong places. To be fair, they knew better and said as much in their discussion.

“The use of home dialysis requires stable housing, as well as the ability to learn and self-administer complex medical regimens, family and caregiver support, and the financial resources for potential home modifications and higher utility bills. The application of pay-for-performance incentives to dialysis facilities does not address these patient-level barriers.” [emphasis added]

Having had some experience with home dialysis, I would add that the stable housing requires significant space for equipment and supplies. In the case of peritoneal dialysis, several hundred pounds of fluid are delivered, and homes with stairs make that a hefty lift. In addition, there is a need for meticulous care and adherence to sterile technique.

Although no improvement was noted, the value of this study, lies in not continuing to persist or to add, as CMS had done, “a ‘health equity adjustment’ to the experiment to reward providers that show more improvement in low-income patients.” It is time to address those patient-level barriers. To do that, we must look beyond the obvious involvement of physicians and dialysis centers and find ways to improve education and housing. Some will rightly argue that these are issues outside the scope of CMS (an argument far more likely to have teeth now that the Chevron doctrine has been abandoned). However, if we wish to lower our ESRD costs, we must move those incentives to those other social determinants.

Source: Pay-for-Performance Incentives for Home Dialysis Use and Kidney Transplant JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.2055