When I was in elementary school, I remember going to the county health department before every school year. There were many other kids there, and we were all there for the same reason: shots. Like terrified, trembling puppies at the vet, we all knew what was coming — and the sound of a screaming kindergartener meant that the nurse had created yet another happy customer. Next!

Now, imagine a world where this didn’t have to happen. Instead of injecting your little rugrat with a needle, the nurse simply slaps a patch on their arm and sends them on their way. That world could exist right now — and it would benefit not only wailing toddlers in this country but poor kids all over the globe.

Microneedles

Vaccine patches work because of a technology known as microneedles. True to their name, microneedles are tiny: 150-1500 µm long, 50-250 µm wide, and a tip diameter of 1-25 µm. Importantly, unlike hypodermic needles, they do not penetrate far into the skin. As a result, they don’t trigger pain receptors located deeper in the dermis, making their application painless.

There is a lot of buzz surrounding this new technology, but scientists still want to make sure that they work well. So far, research indicates that they do, sometimes even better than traditional needles. Still, there is more to learn, and a new study published in The Lancet aimed to be the first to test the safety and efficacy of a measles and rubella vaccine microneedle patch (MRV-MNP) in children.

The researchers enrolled 45 adults, 120 toddlers, and 120 infants from The Gambia in the study, but the infant cohort was the most interesting, as they were immunologically naïve to MRV — that is, they never had been vaccinated against measles and rubella. (Despite that, a few of the infants had antibodies against them at baseline, likely due to environmental exposure to the viruses.)

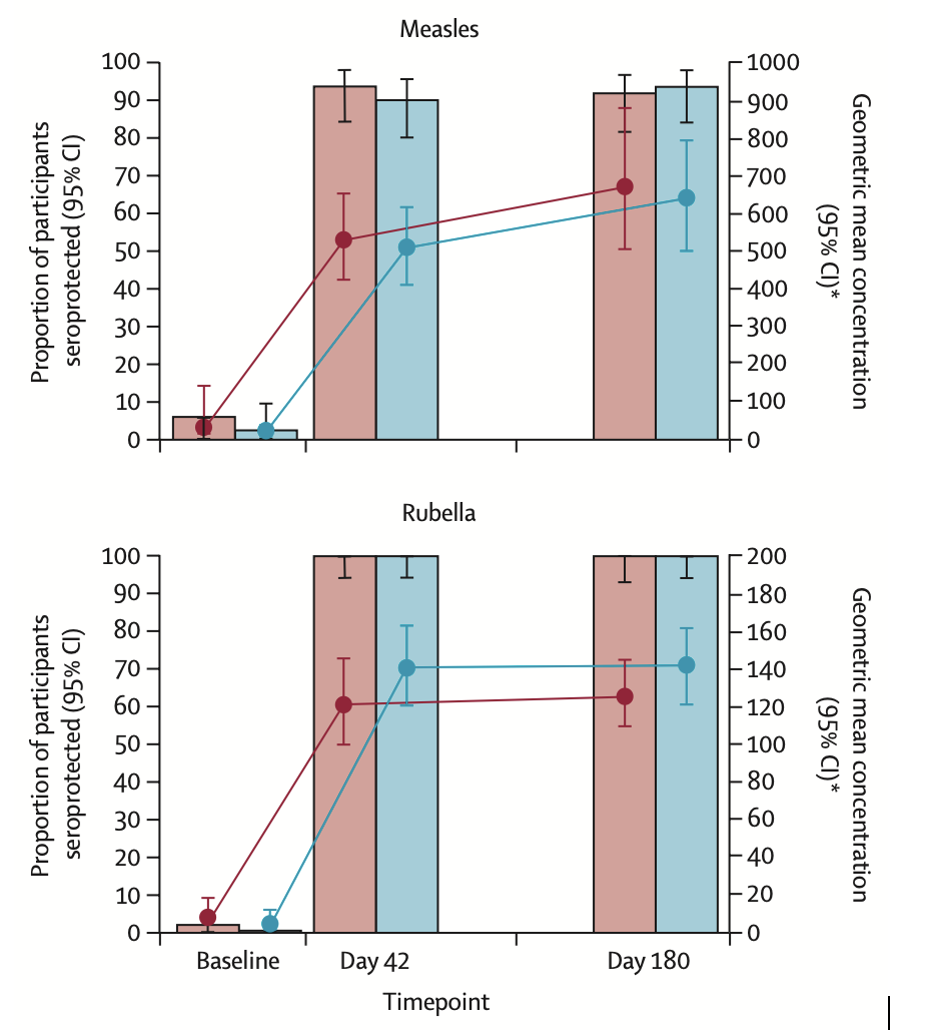

The results are shown in the charts below. The red bars represent infants who had received the vaccine patch plus a placebo shot, while the blue bars represent infants who had received a placebo patch plus a legit MRV shot. Both worked extremely well, as measured by the percentage of infants who were seroprotected (that is, had developed a sufficient antibody response) against the viruses at day 42 and day 180. Just over 90% of infants in each treatment group were seroprotected against measles, while 100% in each treatment group were seroprotected against rubella.

Source: Adigweme I, et al. The Lancet. 2024.

Side effects were minor, mainly limited to redness and induration (that is, hardening and thickening of the skin due to inflammation). Those side effects were largely absent from the infants who received a placebo patch. But, of course, most parents would trade a bloodcurdling scream for a minor rash. Indeed, vaccine patches should come with the slogan, “No more tears.” Too bad Johnson & Johnson trademarked it for its baby shampoo.

Vaccines of the future

Nobody likes getting jabbed, even adults. One study suggested that if we could get rid of needles, we would eliminate 10% of vaccine hesitancy cases. For many people, therefore, fear of vaccines is based not on the contents of the syringe but the fact that there’s a syringe.

Given all their benefits, microneedle patches almost certainly will be the vaccines of the future. The biggest obstacle is finding the best way to manufacture them at scale, which will require a lot of research and trial and error. Some potentially good news is that microneedle patches can be 3D-printed. They also may not require a cold chain (a series of refrigerators), which would make it much easier to deliver them to people in isolated areas of poor countries. They also don’t require a medical professional to administer them, as there’s nothing particularly complicated about slapping a patch on someone’s arm.

Source: Adigweme I, et al. A measles and rubella vaccine microneedle patch in The Gambia: a phase 1/2, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, active-controlled, age de-escalation trial. The Lancet. 2024;403(10439):1879-1892. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00532-4