Let me begin with the caveats – it is a research study of the UK Biobank, which in the authors' words, “is not fully representative of the UK population regarding lifestyle and characteristics.” Ninety-four percent+ of the participants were White. Lifestyle assessment was self-reported and only when the participant joined the Biobank. Most importantly, disease free refers to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia – all significant but certainly not comprehensive, especially when considering debility and a disease-free interval.

After exclusions for the presence of baseline chronic disease, there were 135,199 participants. During a mean follow-up of roughly 12 years, there were 4656 deaths, 11,427 cardiovascular events, 2786 patients with onset of diabetes, 12,688 diagnosed with cancer, and 808 with evidence of dementia.

Scoring participants' cardiovascular health, the researchers used a metric promoted by the American Heart Association, the LE8, which incorporates the following, each on a 100-point scale.

- Diet [1]

- Physical Activity

- Combustible Smoking

- Sleep

- BMI

- Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [2]

- Blood glucose

- Hypertension

Scores are summed, divided by eight, and placed in three categories, low (LE8 score<50), moderate (LE8 score≥50 but <80), and high (LE8 score ≥80). With these preliminaries out of the way, what did they find?

- The mean LE8 score was 66.2 for men and 71.0 for women. More men had lower LE8 scores than women in the low and high categories.

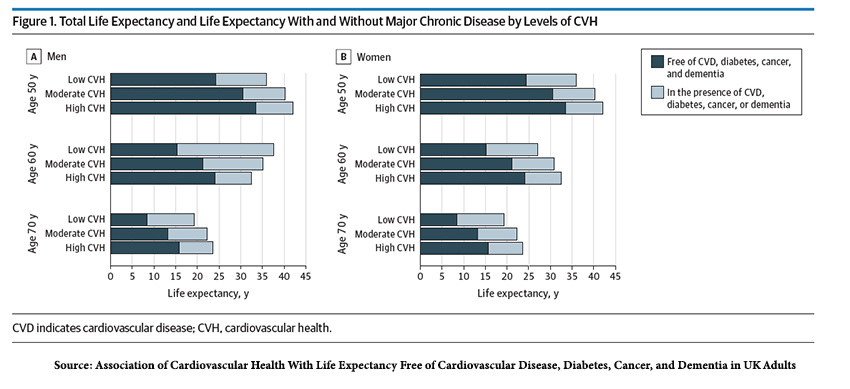

- Higher levels of cardiovascular health, the LE8, were associated with longer life expectancy and a longer disease-free interval.

- At age 50, men lived an average of 4 or 6.9 years longer, free of chronic disease, if they were in the moderate or high LE8 category compared to the lowest LE8s. For women, those values were 6.3 and 9.4 years.

- All of the individual measures within the LE8, except for non-HDL cholesterol, were statistically significant in extending “life expectancy free of major chronic disease” in both men and women.

- Higher levels of LE8 extend total life expectancy and the disease-free interval, but with a mismatch such that the disease-free interval took up more of the life extension, “leading to a compression of years of life lived with disease.” Here is that data.

For women and men, the drivers of longevity were not smoking, a low BMI, and an absence of hypertension. For women, you could add a low glucose. The contribution of diet, activity, and a bad lipid profile was less than those factors.

Of course, no study today would be complete without considering the social determinants of health, in this instance, deprivation [3], income, and education.

- Lower levels of socioeconomic status reduced male life expectancy free of disease, at age 50, by 0.6 to 1.4 years, predominantly from low educational attainment. For women, the reduction was 0.4 to 1.6 years, in this instance, due to household income.

- For participants with high LE8 scores, there was no statistical significance in disease-free life expectancy between those in the lowest and highest socioeconomic groups.

These findings, taken together, suggest that social determinants of health indeed impact the quality of life. More importantly, within the LE8 factors, one might control diet, activity, smoking, and sleep. Focus on those lifestyle “choices” can theoretically make a difference, it would be good to see programs that can deliver on that promise.

[1] The DASH or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension was the referent diet in this case.

[2] This measures not only LDLs, the measure we usually consider in evaluating cholesterol risk but all the “bad cholesterols.”

[3] You have to love the Brits' word choices. The Townsend Deprivation Index, which considers unemployment, household overcrowding as well as a lack of home or car ownership

Source: Association of Cardiovascular Health With Life Expectancy Free of Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, Cancer, and Dementia in UK Adults JAMA Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0015