Are there symptoms associated with what is being called Long COVID, unique for the long-term effects of this specific viral infection? Or can it follow any viral infection or no infection at all? To get that answer, researchers used the electronic health records (EHR) of 17,487 patients spread across 122 US healthcare systems, all members of the Cerner EHR family [1]. Before diving into the data, an important word of caution. There is no standard definition for many of the terms checked off in an EHR, especially vague terms like fatigue. Without a data dictionary defining those terms, fishing in the waters of Big Data comes with uncertainty. Cloaking the findings with p-values does not eliminate the fact that some of the data entered just ain’t so.

Using diagnostic codes, something we would term “administrative” data, the researchers defined three groups: those with pneumonia attributable to COVID, those with pneumonia attributable to other viral infections, e.g., influenza, and a group without pneumonia at all. To be attributed to COVID, the incidence of a symptom had to be statistically significant compared to both those with a general viral respiratory infection (VRI) and the control group. [1]

An initial COVID infection was a “significant positive predictor” of subsequent:

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath) and Chest pain – While COVID did have a higher occurrence of pulmonary embolism, hypoxia, and pneumonia, compared to viral respiratory infection, it was no more significant than that seen in the control group.

- Palpitations – a “noticeably rapid, strong or irregular heartbeat” was the only cardiovascular symptom distinguishing COVID from other VRIs. More objective findings, such as heart failure, tachycardia, an elevated heart rate, and thrombotic events, were not significantly different.

- Fatigue and Joint pain were the only musculoskeletal symptoms unique to Long COVID.

- Hair loss was a unique finding in Long COVID, but its magnitude increased over about eight months and then, as might be expected or hoped for, returned to baseline levels.

There were no increases in neurologic symptoms such as loss of smell, anosmia, anxiety, or depression. While cognitive impairment, COVID’s brain fog, was increased compared to patients with other VRI, it was not significantly increased compared with the controls.

The patients studied were more frequently female, 66%, and white 73%. Long COVID increased with age, peaking in the age group of 50 to 64. All these demographics might limit the applicability of the findings. Shortness of breath, fatigue and joint pain were Long COVID’s commonality – all subjective findings. That may be the best we can do, for the moment, in unpacking the riddle of Long COVID.

The researchers write that 40% of Americans have had COVID, and 20% of them may experience Long COVID – 8% of our population. But the studies underlying those numbers may be casting too broad a symptom net. We just don’t know. The study also makes it clear that Big Medical Data will not necessarily be the treasure trove of knowledge it was hyped to be.

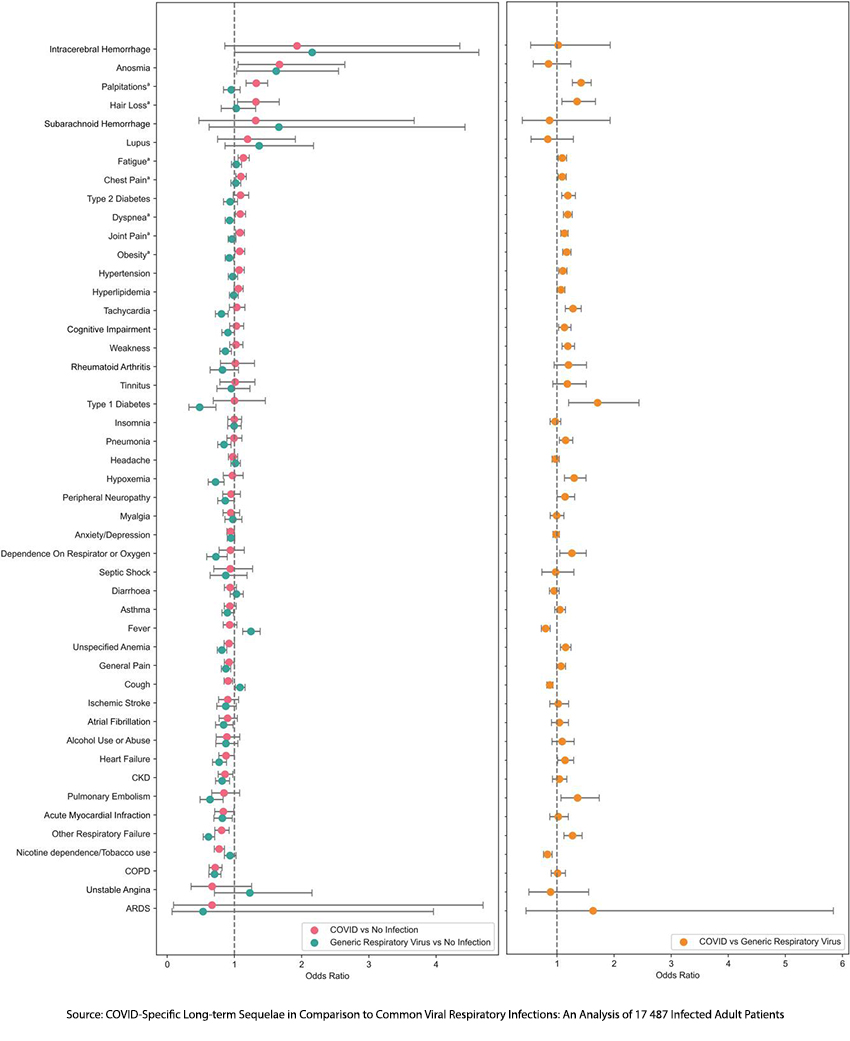

[1] For those who wish to see all the data, here is the Forest plot.

[1] Cerner is one of the largest EHR software companies and has created a data repository for the hospitals that use their systems to hold presumably de-identified patient data for research.

Source: COVID-Specific Long-term Sequelae in Comparison to Common Viral Respiratory Infections: An Analysis of 17 487 Infected Adult Patients Open Forum Infectious Disease DOI: 0.1093/ofid/ofac683