It's mosquito season in the Northeast and we had a very wet spring. Which means there are going to be 1) a whole bunch of mosquitoes, and 2) a whole bunch of people arguing about whether to spray them or not. The purpose of this article is to examine the toxicology of Sumithrin – the active ingredient in the commonly used insecticide Anvil – and come up with a realistic picture of whether Sumithrin is a deadly poison, a non-toxic chemical, or something in between.

Sumithrin, aka d-phenothrin, is a commonly used insecticide which belongs to the pyrethroid family of chemicals – synthetic analogs of the chemicals that are found in chrysanthemum flowers that the plant makes for self-protection against insects (1). Sumithrin is a general-purpose insecticide; it is used to kill or control fleas, scabies, and head lice. It also kills ticks—a benefit I’ll discuss later.

There are a number of standard methods used to determine the risk of chemicals. Here are some of the most widely used.

1. ACUTE TOXICITY

One way to gauge the toxicity of a chemical is to determine the amount of it required to kill 50% of a group of lab animals (usually rats and mice) with a single dose. This measurement is called the LD50, which is short for Lethal Dose 50%. The LD50 is expressed in milligrams per kilogram (mpk) of body weight of the animal. For example, if Chemical X has an LD50 of 10 milligrams per kilogram, then the dose of the X required to kill half the rats would be 5 milligrams (an average rat weighs 0.5 kilograms). If Chemical Y has an LD50 of 2,000 mpk this means that it would take 100 mg of Y - about 20% of the body weight of the animal - to kill half the rats. This is an enormous dose for a rat or any other mammal.

So, a high LD50 means that the chemical in question has low toxicity. Conversely, a low LD50 indicates that the chemical has significant toxicity. Although LD50 values in rodents cannot be directly converted to a lethal dose in humans, they serve as a rough approximation of human toxicity, especially when these values are consistent across a number of different animal species. So, it would be incorrect to say that the lethal dose of Chemical X, which is 5 mg in rats, would be 700 mg in humans (average weight 70 kilograms). But it would be fairly safe to conclude that Chemical X will be more toxic to people than Chemical Y, and probably by a lot.

LD50 VALUES OF SOME CHEMICALS AND DRUGS

The scientific literature contains an enormous amount of data on the toxicity chemicals. One especially useful source is TOXNET, an NIH website which contains toxicity and carcinogenicity data, etc. on 400,000 chemical compounds. All of the toxicity data contained in this article is derived from the TOXNET database.

Figure 1 contains rat LD50 values for selected chemicals and drugs.

Figure 1. LD50 values of sumithrin and other representative chemicals and drugs. Strychnine (top) is the most toxic chemical in the group. Toxicity decreases from top to bottom.

* The value for aspirin is the average of two peer-reviewed studies.

** The LD50 values of sumithrin and aspartame (NutraSweet) are not 10,000 mpk; they are higher than that. No lethal dose in rats could be identified for either chemical, so the value is usually written as >10,000. When something has an LD50 of >10,000 the only way it will kill you is if you get run over by a truck carrying it.

Of the nine chemicals and drugs listed in Figure 1 acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the least toxic, with the exception of aspartame and sumithrin, which are non-toxic. Calculating a lethal human dose, as I mentioned before, cannot be done by using the same LD50 value and adjusting the dose size from rats to humans. But just to illustrate the lack of acute toxicity of sumithrin, I did the "math" anyhow. If rat LD50 values were the same as those of humans, then the toxic dose of sumithrin in people would be 182 grams - 36 teaspoons. You are unlikely to eat 36 teaspoons of permethrin.

2. CUMULATIVE EXPOSURE

Most people have an incorrect impression about everyday chemicals that we are exposed to. They believe that we live in a cocktail of toxic substances, which build up in our bodies and that this is responsible for the surge in cancer rates we are now seeing. There are two problems here:

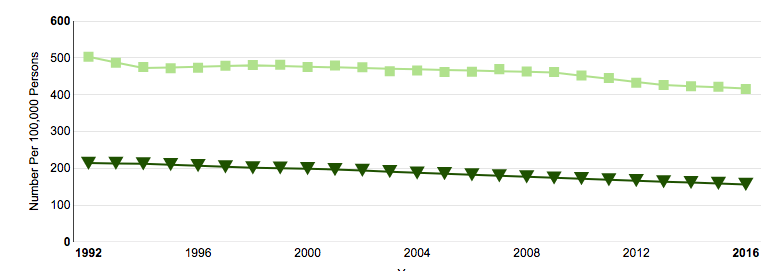

1. There is no surge of cancer rates. They have remained steady or slightly declined over the past 24 years.

Age-adjusted incidence (top) and mortality (bottom) of all cancers (per 100,000 people) between 1992-2016. Source: Cancer Stat Facts: Cancer of Any Site.

2. With few exceptions, chemicals do not accumulate in our bodies. This is because of our livers – the primary site of metabolism of drugs and chemicals, natural or synthetic – break down the chemicals or drugs that pass through them, converting these substances into water-soluble metabolites that are usually excreted in the urine.

Sumithrin, like most chemicals, does not bioaccumulate. In rats, the half-life in blood is about one hour (rapid metabolism), meaning that after one hour half of it is gone and after 8 hours (four half-lives) almost all of the sumithrin is gone. Even after administration of a single 200 mg dose (2% of the weight of the rat), more than 95% of the chemical was metabolized and eliminated after 48 hours.

Also, keep in mind that these numbers represent the fate of sumithrin when taken orally. Sumithrin is not very efficient in penetrating the skin, so skin exposure will give low blood levels to begin with. Even though the chemical has very low toxicity when inhaled by rats, when it is inhaled in large quantities by humans, sumithrin can cause "nausea, vomiting, throat irritation, headache, dizziness, and skin and eye irritation," but the hysteria surrounding spraying is unwarranted. According to data from the Poison Control Center between 1992-2005, there was an average of 180 exposures per year with only 25% of these (45) resulting in symptoms (2). So it is not surprising that a 2011 paper, "Bystander Exposure to Ultra-Low-Volume Insecticide Applications Used for Adult Mosquito Management," concluded:

"Our results support the findings of previous risk assessments that acute exposures and risks to humans from [Ultra-Low-Volume] insecticides are well below regulatory levels of concern."

C. Preftakes, et.al, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011 Jun; 8(6): 2142–2152.

3. A LITTLE DOES NOT EQUAL A LOT

Although this statement seems self-evident, it is mind-boggling how often people get it wrong by failing to differentiate between the biological effects of trace quantities and a bottle full of the same chemical, even though in the 16th century the Swiss physician Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, aka, Paracelsus, coined the phrase "All things are poison, and nothing is without poison, the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison," which has been shortened to "the dose makes the poison"

Paracelsus, the "father of toxicology." Image: Wikipedia

This simple adage is the main reason that sumithrin can be sprayed to kill mosquitoes while sparing humans. Common mosquitoes weigh 2.5 mg. An average human weighs 70 kilograms, which is 28 million times more than the mosquito. This is why such insecticides can be toxic to bugs but not toxic to people, but it is not the only reason. It is also known that mosquitoes metabolize sumithrin more slowly than humans, so it builds up in the bugs but not in people (3).

4. CARCINOGENICITY

There are a number of ways to evaluate whether a chemical will be carcinogenic in humans. Here are the two most important:

1) Genotoxicity (DNA damage). Chemicals that damage DNA always raise a red flag because gene damage can be a precursor to cancer. Many experimental drugs have met with an untimely demise because of a positive Ames test (3). Although not all chemicals that are genotoxic are carcinogens, most carcinogens are genotoxic. There are a number of other lab tests that are used to determine the possible carcinogenicity of chemicals.

2) High dose rodent studies. Rat models of cancer are notoriously awful. Part of the reason is that rats are not little humans, but the primary reason is the way the tests are conducted. Typically, rats are fed a very high dose – much higher than a human will ever be exposed to – for their entire lives (two years) and then examined for tumors. Although this model is clearly unrealistic, the high dose feeding is only part of the problem. The choice of rats is the other. The Sprague-Dawley rat is frequently used for this experiment; this rat is bred to easily develop tumors, so much so that the control animals (not given the chemical being tested) develop so many tumors that it can be difficult to determine whether a chemical caused the tumor or the rat developed it on its own.

Sumithrin is neither genotoxic nor carcinogenic. There is no agency, US or international, that lists the chemical as a possible carcinogen. Even California's insane Proposition 65, which requires cancer warning labels on hundreds of chemicals (also on hotel rooms, in cars, handbags...and much more) does not contain sumithrin. But the list does contain alcohol – a known human carcinogen. It would be unusual to see people hiding in their homes with the windows closed and air conditioners running when people walk by drinking beer.

5. OTHER LIFE FORMS

Sumithrin is more toxic to dogs and (especially) cats than it is to rodents, birds, or humans. The primary routes of exposure include flea collars and indoor foggers. Sumithrin is highly toxic to bees, fish, and amphibians. It should not be sprayed in waterways.

6. PERSISTENCE IN THE ENVIRONMENT

Sumithrin decomposes to non-toxic breakdown products within a few hours (in the air) and less than a day on the surface of plants. Its half-life in soil is 1-2 days and it is not water-soluble, so groundwater contamination is unlikely.

7. TO SPRAY OR NOT TO SPRAY

It is easy to conclude that any given chemical or drug should not be used if one examines only the risks of using it without considering the risks of not using it. Both mosquitoes and ticks are vectors for numerous (and emerging) bacterial and viral infections and when they are not controlled, human disease will inevitably result.

West Nile (mosquitoes) and Lyme (ticks) are well-known, but other pathogens transmitted by mosquitoes can be deadly. Chikungunya virus, once rare to the US, is now found in 35 states. The infection is rarely fatal but can be incapacitating for weeks. Dengue virus is endemic to Africa but has now been found in Texas, Hawaii, and the Florida Keys. Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) perhaps the most dangerous of all mosquito-transmitted diseases, so much so that it is considered to be a potential bioterrorism weapon. It is spread to horses and humans by mosquitoes. Although still rare, the fatality rate for infected humans is 50-75%. Zika, which causes severe birth defects in the babies of infected mothers, Western Equine Encephalitis, St. Louis Encephalitis, and LaCrosse Encephalitis are still uncommon but all are now found in the US. All of these viral infections are spread by mosquitoes. (5)

In addition to Lyme, ticks spread a number of viral infections, such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Colorado Tick Fever, and Powassan Encephalitis.

At the heart of this controversy is the fallacy that "natural is better." It is not, despite the brilliantly successful advertising campaign of the organic food industry, copycat traditional food manufacturers which have hopped on the bandwagon, and the dietary supplement industry, which has pushed such ridiculous claims to the point where they resemble satire. The only difference between "natural" substances and their man-made counterparts is the source of the chemical or food. Your body cannot tell the difference between a chemical from a grape or one from a lab. All that counts is the properties of the chemical in question. Virtually all of the "natural" Vitamin C you buy comes from factories in China, where it is manufactured from glucose. Yet, it is no different from Vitamin C extracted from oranges.

Public health decisions require sound science, not reflexive reactions based on misinformation, ignorance, or personal beliefs. Whether the issue is vaccination or pest control, feel-good, easy-sounding memes may be attractive alternatives to actual facts, but in the absence of sound science the easy answer is usually the wrong answer.

NOTES:

(1) Insecticide marketers engage in a sleight-of-hand by saying pyrethroid insecticides are in the same chemical family as the natural pesticides from chrysanthemums. This is technically true, but meaningless. It implies that the insecticides are somehow safer because they are "related" to chrysanthemums. That is nonsense. Each pyrethroid has its own toxicity profile. Sumithrin is safe because it is non-toxic, not because it is structurally similar to the natural insecticides.

(2) Reference: d-Phenothrin (Sumithrin®): Occupational and Residential Exposure Assessment for the Reregistration Elibibility Decision (RED); U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances, Office of Pesticide Programs, U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, 2007; pp 1-23.

(3) Another "active" ingredient found in Anvil insecticide is piperonyl butoxide. Piperonyl butoxide is not an insecticide, rather, it inhibits the enzyme that clears sumithrin from the mosquito, making it more effective. Piperonyl butoxide is neither toxic nor carcinogenic. There is one case report of a fatal overdose, but the victim drank between one pint and one quart of the chemical.

(4) The Ames test, a widely used and important method for determining carcinogenicity uses bacteria to test for the ability of chemicals to mutate genes. It was invented by biochemist Dr. Bruce Ames in the 1970s. Ames was one of the founders of ACSH.

(5) This information is available from the American Mosquito Control Association, a non-profit group funded by the CDC.