While many people would rather never think about it, we're increasingly living in a country where wastewater is not only recaptured – but oftentimes it's treated so that it can be added to the water supply that flows from our taps at home.

Just the thought makes some cringe. The truth, however, is that it's being done, and while that might be a surprise to some, testing has shown that recaptured, treated wastewater is safe to drink. Previous news reports have informed us that nearly all contaminants can be removed; some stories appeared on national broadcasts.

But now researchers are looking at the water glass from another angle. They wanted to learn that if they put recycled water side by side with other sources, could participants in a blind taste test tell the difference?

And after conducting a limited study, the answer was no – they could not. In fact, researchers found it was preferred to tap water.

In a paper published recently in the journal Appetite, scientists from the University of California, Riverside had 143 subjects sample water from three sources: (1) conventional tap water, (2) bottled water and (3) "IDR-treated tap wastewater," or water produced via a process known as indirect potable reuse.

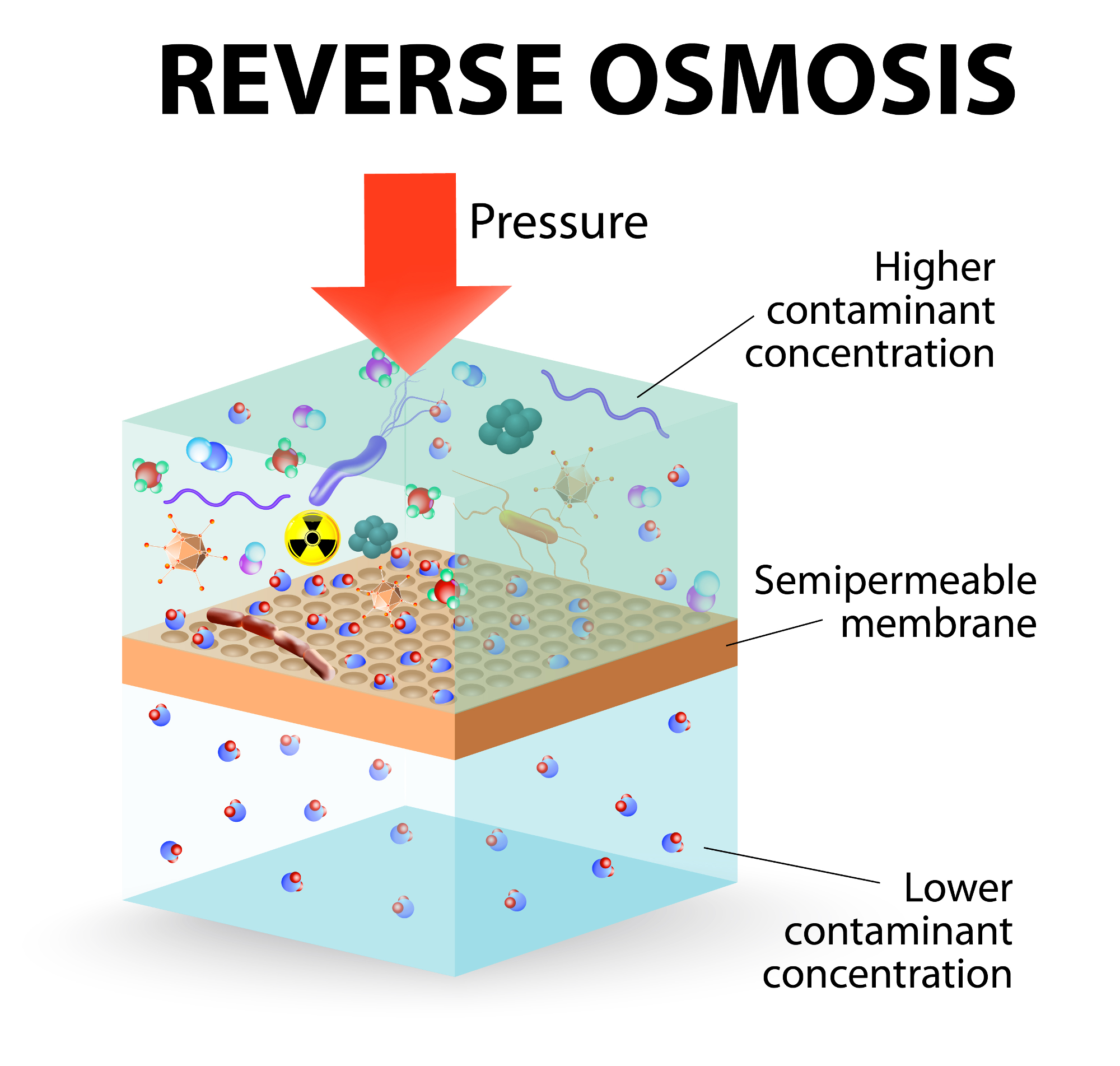

IDR treats the water using reverse osmosis, which captures and removes salts, chemicals and viruses, according to Trojan Technologies, a Canadian-based water treatment company. For the purposes of reuse in communities, IDR, according to the study's authors, "reintroduces treated wastewater into groundwater supplies, where it re-enters the drinking water system." For the purposes of this study, it was given to participants in unmarked cups alongside the other two water sources.

IDR treats the water using reverse osmosis, which captures and removes salts, chemicals and viruses, according to Trojan Technologies, a Canadian-based water treatment company. For the purposes of reuse in communities, IDR, according to the study's authors, "reintroduces treated wastewater into groundwater supplies, where it re-enters the drinking water system." For the purposes of this study, it was given to participants in unmarked cups alongside the other two water sources.

After each subject graded what they drank and the results were tallied, IDR water was given a similar ranking to bottled water. Meanwhile, groundwater was graded least appealing because it had "higher pH levels and lower concentrations of Ca [calcium] and HCO3," or bicarbonate.

"We think that happened," said Mary Gauvain, a UC Riverside psychology professor and the study's co-author, "because IDR and bottled water go through remarkably similar treatment processes, so they have low levels of the types of tastes people tend to dislike."

The issue of reusing wastewater has received greater visibility as a result of the recent four-year drought in California, where IDR processing is becoming more and more acceptable. The study's authors cite that six of the state's "water agencies already employ IDR ... the Water Replenishment District of Southern California, the Orange County Water District, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works, the Inland Empire Utilities District, the city of Los Angeles, and the city of Oxnard."

Meanwhile, earlier this month in the Midwest, the Kansas Health Institute proposed that wastewater recapturing be strongly considered to supplement the existing water supply. "That wastewater can be treated for industrial use," reported the Topeka-Capital Journal, "or treated with advanced techniques to meet or exceed the quality of drinking water."

The Kansas debate did not include consuming IDR-processed water, but using it to serve the community. A resident survey conducted by the Institute "found that 75 to 90 percent favored reusing water to irrigate parks, schools and golf courses, as well as supply fire hydrants," the newspaper wrote. "They were less willing to support use of recycled water in a car wash or crop irrigation."

That said, the topic of recycling wastewater is becoming, shall we say, more mainstream all the time.