When it comes to survival, birds are not birdbrains.

A recent Australian study in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution found that birds can adapt to urban environments better than we thought. But before we get to that, I do have a bit of a problem with one sentence in the introduction:

"Although people garner a number of benefits from roads, including transportation of goods and services and connectivity, roads exert a variety of negative effects on the surrounding environment: from changes in animal and vegetation communities"

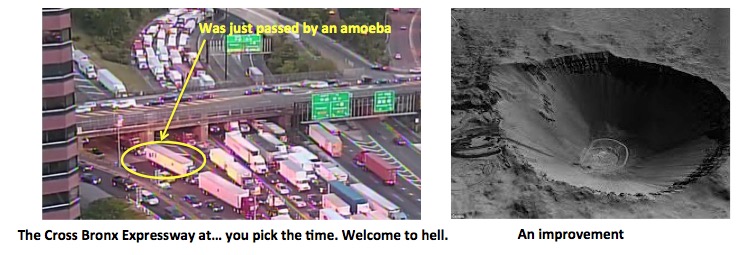

OK, this sounds like a full timeshare in the Crazytown Condos. A number of benefits??? A wee bit of an understatement if you ask me. I don't think that modern life would be so great without roads. For example, how would we get essential products such as Cap'n Crunch delivered (see Figure 1)?

Of course, there are exceptions. One could reasonably argue that a strategically placed nuclear device on the supernaturally misnamed Cross Bronx Expressway would benefit New York.

Back to the birds.

Christopher Johnson, a graduate student at the Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia, conducted this research along with Professor Darryl Jones in an attempt to determine how much roads impact the natural movements of birds. The answer: not as much as you'd think. Johnson is an avid bird watcher who spent a considerable amount of time observing the behavior of different types of birds near different types of roads, something that many people might normally dismiss because, unlike other wildlife, birds can fly over the roads rather than walk across them. But they don't necessarily do so.

By comparing the number of birds at the side of the road (where they may or may not run into the chicken, who last I heard, was undecided about crossing the road) with those 100 meters away Johnson was able to establish some unexpected patterns in bird behavior. Different types of birds behaved differently.

For example, when wide roads (six lanes) were compared to medium (four lanes) and small (two lanes) roads, it is not surprising that fewer birds were found near the bigger roads than the small. The effect was greatest in forest-dwelling birds; they avoided areas with wide roads. While this is intuitively obvious, some of the other findings were not.

Predatory and aggressive (usually larger) and "urban tolerant" birds not only didn't have much of a problem with highways but even seemed to like being near them, presumably because the roads served as territorial markers. Birds that were preyed upon wanted nothing to do with any of the roads.

There is some evidence to suggest that some birds may benefit from roads: power-lines, signs and roadside vegetation may serve as useful ecological corridors through the provision of suitable nesting, refuge and perching habitats

Source: Front. Ecol. Evol., 02 May 2017

The avoidance of roads by smaller, forest-dwelling birds may have multiple factors. For example, not only is environment near the road very different from theirs but it also is a wide open space, which birds who may become meals tend to avoid. And the fact that predatory birds camp out near the road is just one more reason that the little guys want to "hit the road" when near the road.

Daryl Evans, one of the co-authors, who are interested in minimizing contact between man and nature wrote: "There are wildlife-friendly solutions to many of these issues, such as specially-designed overpasses, fauna underpasses, and fencing so animals can avoid accessing the road, all of which need to be incorporated into the design of our road systems."

We nature nuts applaud simple, sensible solutions such as this. It won't alter the earth's climate or stop billions of tons of plastic from fouling our waterways, but it might just give us a few more birds to listen to.

If you're wondering how I came across this story, the answer is obvious - A little bird told me.