As a society, we immediately understand a broken arm. A gaping wound. The wasted appearance of a body overrun by cancer. But, often there are more silent and invisible conditions that not only wield a physical furor, but also an emotional and psychological one.

Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is such a malady. Its manifestations influence not only the afflicted, but also their loved ones, community and care givers. Such is the case with Alexa Besser, featured in the photo accompanying this article, whose story and benefits from much enhanced and innovative technology will be addressed shortly.

The tiers of worry that accompany parenthood, in general, get amplified when a child suffers from a chronic disease. With respect to T1D, a parent compounds such fears with the realization that reliance on the public at large is essential to their child’s well-being and survival. Extended delay in comprehension of such a condition can serve to do great harm as can unpredictable events like fire alarms or being stuck in an elevator without proper medical equipment. Such is the constant challenge of invisible diseases, especially this one. (1)

The current, focused narrative when discussing diabetes has been on Type 2 given that numbers are rising and there is a perceived modifiable component to it, obesity. Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are very different. Though they can lead to similar secondary complications and contribute to significant health care costs, their clinical courses, treatment regimens and impact are quite disparate.

Type 2 typically occurs in adulthood— though we are seeing younger rates of disease due to increasing insulin resistance and obesity— and involves retention of an ability to secrete insulin which is necessary to convert sugar (aka glucose) for energy. Patients can take oral medicine to optimize the function of the insulin and can in many cases (if early enough) reverse the condition with an alteration in lifestyle.

With more mild disease, they can retain somewhat of an independence not known to a person with T1D.

T1D is an autoimmune condition in which the body is confused and attacks its own pancreatic cells that are responsible for producing insulin—thereby requiring the individual to replace it by injection or pump for the rest of his life. It comes on suddenly at any age. As of now, there is no cure and giving insulin along with continuous glucose monitoring is the mainstay of management — as is detecting, preventing and treating the secondary issues T1D may prompt. (2)

The delicate dance of living life and keeping eating and insulin regimens in balance to prevent sugars from going too high or too low is unrelenting. The devastating consequences of diabetes can be blindness, impaired wound healing, heart attacks and cardiovascular disease, strokes, kidney damage, increased susceptibility to infection, issues with pregnancy and so on. Though difficult and often upsetting, those who battle it can still lead vibrant and inspiring lives while being true warriors.

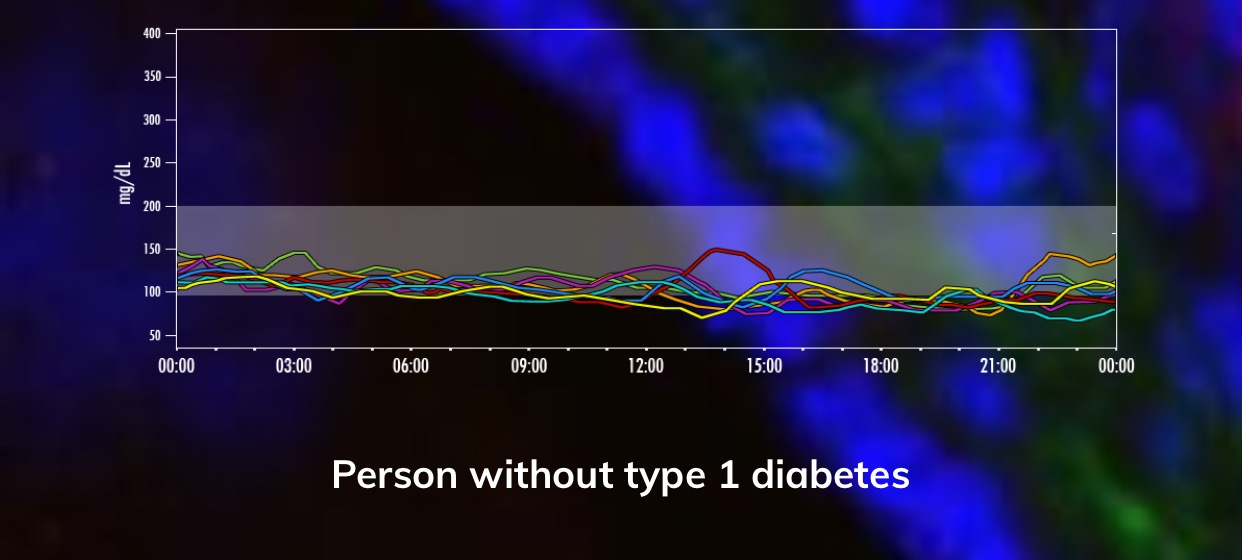

Adjustments must be made when a patient is under extreme stress or sick as glucose levels can run way out of whack. Nature will always provide a superior means of regulating this compared to the diabetic in even the best control. The graphics to follow are courtesy of The Human Trial described later in the article and show the variability of blood sugars for those with and without disease.

Now 5 years old, Alexa Besser was diagnosed with T1D when she was 3.5. Like many others, she had a preceding illness (in her case a streptococcal throat infection) before presenting with an increased thirst and bed wetting. Though the exact cause of T1D is unknown, genetics and environmental influences like infections are believed to play a role. As a pediatrician, I always echo the sentiment that parents know their children. Alexa’s mother Michelle instinctively knew something was wrong and brought her to the doctor, insisting her urine and blood be tested. Understanding that the signs can often mimic stomach bugs and delay proper treatment, she is grateful Alexa did not go undiagnosed and endure a diabetic ketoacidosis (a life threatening consequence) or coma as a result.

Sure enough, Alexa had T1D.

“This has been a life changing diagnosis for the entire family,” Mrs. Besser conveys. “Monitoring Alexa’s sugar is a 24/7 job. There are no breaks or holidays. The scariest part is the danger of low blood sugar while she is asleep or the possible future complications from high blood sugars. The most frustrating thing about diabetes is that there are so many factors that affect her like food, exercise, and hormones etc. Fortunately, technology has made living with this disease more manageable. My hope is that one day Alexa will not have to think about her blood sugar. It will just be regulated either by improved technology or even better, a cure.”

As with most parents of children with chronic disease, the Bessers had to become medical experts overnight. Appreciating that the signs of hypoglycemia are crucial to averting severe problems like coma and death, parents and loved ones become quite attuned to warning glances and expressions that will necessitate their call to action. It is like being on high alert all the time.

This is why the emotional and psychological toll of the disease can’t be overstated. Among the ever present worries include an anxiety over hypoglycemia, broken devices, adverse effects on siblings and the fatigue of care giver burnout, to name a few. Tack onto that an often confused public who may mistakenly associate Type 1 with giving a child too much sugar. This is why awareness is so important and the discussion gets nuanced on all forms of diabetes from T1D to gestational to Type 2 and how the care for each individual requires personalization and customization.

Helping organize events like Saturday’s “One Magical Gala 2017: Make Type 1 Disappear” on behalf of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation’s (JDRF) South Jersey Chapter to raise money for cure, families like the Bessers further the incredible work being done to advance progress in the field. I was deeply touched to attend and celebrate the evening’s honoree, Dr. John M. Tedeschi—my childhood pediatrician.

Dr. Tedeschi enjoys a litany of achievements that could make for a whole other article— least of which includes being among Modern Healthcare’s Top 300 Most Influential People in Healthcare. But, he was especially proud and cherishes this JDRF distinction as he has cared for so many with this disorder and fundamentally understands the mission to eradicate T1D. His words were quite powerful and optimistic about the tremendous strides he witnessed in management of T1D from the beginning of his career until his retirement from practice and with respect to what the future holds.

It is here, in particular, that I echo his sentiment. Throughout the span of my own career in pediatrics, there has been a ton of development. Alexa is a perfect example. According to her mother, “with our first pump she had to wear the actual device that was connected to her by tubes to her skin. She used to take it off a lot and several times missed her dose of insulin. Now, she uses the Omnipod for her insulin pump (changing the site every 3 days) which has been a game changer. Since it is tubeless, it is less attached to her and it’s just a pod that is wireless. Dexcom (changes every 2 weeks) is her continuous glucose monitor. We don't have to prick her finger all the time. It alerts us when she is low which is a dramatic benefit in the middle of the night. So we can give her juice to prevent coma, death etc.”

For a child not to require constant injections and finger pricks is a major innovation. For Michelle Besser, though “her regimen is dose insulin for everything she eats -- even a piece of gum-- and the pump is programmed to deliver basal insulin, we deliver all insulin via the pump. We don’t do needles any more.” Needs vary dependent on many factors like age, variability of disease as well as other co-morbidities, for example. The exact same plan is not a one-size-fits-all and warrants shared decision-making with your doctor and treatment team.

Like most with T1D, major fluctuations occur with sickness, stress and growth spurts requiring constant adaptability. Also, the need to vary placement locations of these types of devices is important in minimizing scar tissue and irritation so as not to impede insulin delivery. Despite the extraordinary progress, advocacy won’t and shouldn't stop until there is a cure.

Hence, this is why Mrs. Besser is hopeful for the encapsulated beta cell replacement therapies presently underway and the closed loop pumps (aka artificial pancreas) in the works. Many promising paths are being explored when it comes to a cure for T1D. Like with other scientific research and medical device enhancements, cautious optimism is a solid approach. Set backs and drawbacks are inevitable and the benefits of a therapy must outweigh the risks especially if severe.

In the Fall, ACSH’s President Hank Campbell wrote about the recent FDA approval for Medtronic’s MiniMed 670G being a waypoint to an artificial pancreas, click here. The JDRF summarizes nicely what research is taking place—and in need of funding— employing stem cells, immunotherapy, or pancreatic/islet transplantation — reviewed here. The Human Trial is a feature-length documentary about the trials and triumphs of ViaCyte in San Diego. It captures in real-time their FDA-approved embryonic stem cell-derived treatment attempting to cure T1D as it enters human trials (to learn more, go here or here). The clinical trial is listed here.

So, these are exciting times for the T1D community. Unwavering pursuit of cure is essential to maintaining hope and effecting profound change not just for those directly impacted by the disease but for the population at large. By making the invisible visible, we transform the world.

Here are some statistics to consider to appreciate further the urgency of such an important goal:

- T1D is associated with up to 13 years loss of life expectancy

- $14 Billion in annual T1D-associated US healthcare costs

- 1.25 million Americans are living with T1D (which is expected to rise to $5M by 2050)

- The T1D prevalence increased by 21% in those under 20 from 2001-2009

- Less than 1/3 of those with T1D achieve target blood glucose control levels

Note(s):

- The notion of invisible diseases was also explored with regard to Sickle Cell Disease in the following: Dr. Jamie Wells On Al Jazeera TV Discussing Sickle Cell Anemia, Did Gene Therapy Cure Sickle Cell Disease?

- To review the American Diabetes Association’s 2017 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, review this link here.