The American Association of Pediatrics has suggested in its policy statement that the first 1000 days since conception are a critical neurodevelopmental interval and that a poor diet during this interval can adversely impact the long-term health of the child. The current dietary guidelines recommend no added sugar; pregnant and lactating women “consume more than triple the recommended amount of added sugar, surpassing 80 g per day, and most infants and toddlers consume sweetened foods and beverages daily.”

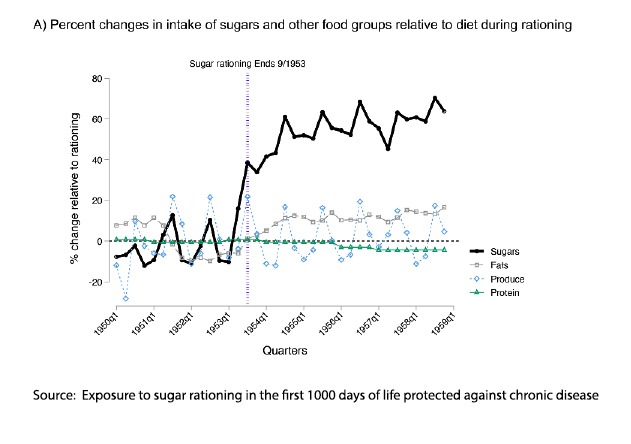

The researchers considered whether “restricting added sugar in the first 1000 days after conception affects the onset of type  2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension decades later,” utilizing rationing in the UK after WWII. As they note, during rationing sugar was restricted for everyone to roughly what are today’s dietary guidelines. When the restrictions were lifted in 1953, consumption immediately doubled, from 41 grams to about 80 grams, providing a “quasi-experimental” variation in sugar exposure – comparing adults conceived shortly before and after rationing.

2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and hypertension decades later,” utilizing rationing in the UK after WWII. As they note, during rationing sugar was restricted for everyone to roughly what are today’s dietary guidelines. When the restrictions were lifted in 1953, consumption immediately doubled, from 41 grams to about 80 grams, providing a “quasi-experimental” variation in sugar exposure – comparing adults conceived shortly before and after rationing.

Deeper analysis showed that total caloric intake increased over the same interval, with “on average 77% of the calorie intake increase post-rationing is due to higher sugar consumption.” Consumption of other nutrients and foods remained largely unchanged by the end of rationing.

Cohort

60,000 individuals from our old friend, the UK Biobank, were identified; 38,000 were defined as having been “rationed,” the remaining 22,000 were defined as non-rationed based on the timing of their in utero and subsequent exposure for a total of 1000 days. Across time-invariant variables, such as gender, race, family history of diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, the two groups were essentially the same.

- The risk of diabetes and hypertension, the primary outcomes increased for both groups as they aged.

- The risk increased more quickly for those in the non-rationed group, especially after age 60.

- The risk of T2DM or hypertension decreased with the duration of exposure to rationing. Those solely exposed to rationing in utero had a 15% lower risk of diabetes, that risk was further reduced as exposure to rationing continued plateauing after 570 days in a 62% reduction. The risk reduction for hypertension was not as great, 6% for those unexposed solely in utero and 21% for those rationed for at least 570 days (19 months).

- The risk of diabetes and hypertension in non-rationed adults remains constant.

- In-utero exposure explained about a third of the total risk reduction; post-natal rationing accounted for the majority of risk reduction.

- Those exposed to rationing only in utero experience a delayed onset of hypertension by about six months and diabetes by 16 months. Extending the rationing post natally increased the delay for hypertension to 2- years and diabetes by 4-years.

While the underlying mechanism remains unclear, environmental circumstances surrounding fetal and early infant development seem to have long-term consequences. In addition to possible genetic alterations and genetic expression, early-life sugar exposure may enhance a preference for sweetness, resulting in a life-long elevation in sugar desire and consumption.

With today’s sugar-loaded diets, it's hard to imagine the possibility of rationing as a health measure. But considering the long-term effects of early sugar restriction, it might be worth rethinking how we feed our youngest generations. Maybe it's time we take a page from history; after all, a little less sugar today could mean fewer health problems tomorrow.

Source: Exposure to sugar rationing in the first 1000 days of life protected against chronic disease Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adn5421