Their eyes tell their sad stories as ghostly white irises give way to vacant stares. We can look at them, but they can’t look back at us. They’ve gone blind because of malnutrition,” lamented V. Ravichandran, a farmer describing children suffering from vitamin A deficiency. “I see these people all over India.”

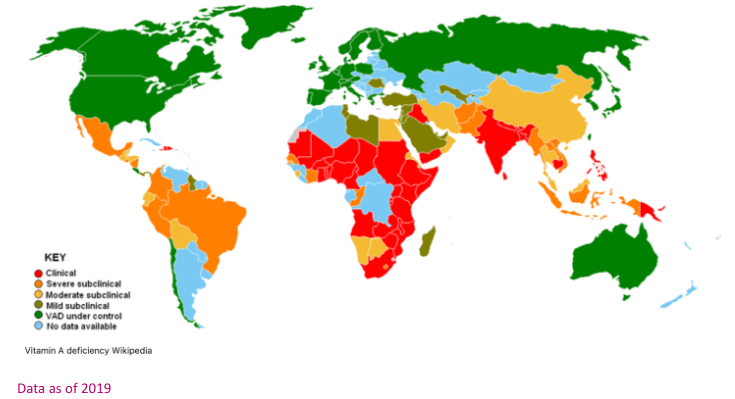

The scourge of blindness and death is a dual tragedy — first, because blindness from vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is an early sign of life-threatening debilitation, and two-thirds of sufferers will die within a year; and second, because VAD could be prevented with the product of an accessible, modern agricultural technology.

Over the years, partly under the guidance of the United Nations, various stop-gap efforts have been instituted to try to slow the scourge, including distributing vitamin A supplements and trying to educate desperately poor villagers about diet changes. They’ve all failed.

There is one, and only one, solution that could work on a global scale: vitamin A-enhanced rice, known as Golden Rice. The only thing blocking this global treatment is a coalition of advocacy groups, led by Greenpeace International, that has intimidated the public and manipulated some regulators and courts into believing that obstructing the genetic engineering revolution is a more important cause than preserving the lives of vulnerable children.

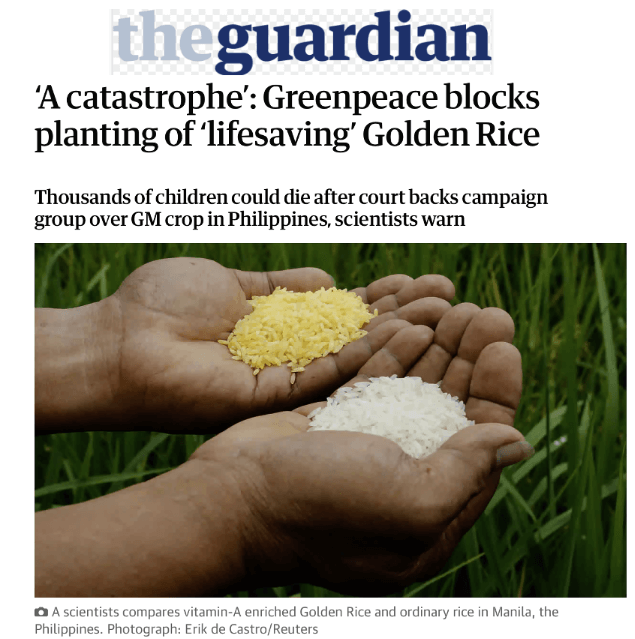

In April, a Philippine court, acting on a filing by Greenpeace, rescinded the country’s commercialization approval of Golden Rice — a ruling even the uber-liberal The Guardian (UK), long a dogged opponent of genetically modified crops and a former ally of Greenpeace on this issue, characterized as disgraceful.

The sudden decision at a time when the first batch of rice was ready for harvest has reverberated across the globe. Scientists from food-insecure nations such as India and Bangladesh fear that the pathway to commercial approval of important genetically engineered crops in their own countries will be more difficult than ever since this most recent setback. The consequences will be felt most acutely by the poor, with potentially 100,000 new deaths of children each year as the outcome.

Golden Rice varieties get their name from their color, which is imparted by the presence of beta-carotene, the precursor of vitamin A. Rice is a food staple for hundreds of millions, especially in Asia. Although it is an excellent source of calories, it lacks certain micronutrients necessary for a complete diet. In developing countries, 200 — 300 million children of preschool-age are at risk of vitamin A deficiency. That increases their susceptibility to infections such as measles and diarrheal diseases. Every year, about half a million children become blind because of VAD, and 70 percent of them die within a year of losing their sight.

In the 1980s and 1990s, German scientists Ingo Potrykus and Peter Beyer developed the “Golden Rice” varieties that are biofortified, or enriched, by the introduction of genes that enable the edible endosperm of rice to produce beta-carotene, the precursor of vitamin A. Rice plants produce beta carotene in the leaves but not in the grains, so Potrykus and Beyer inserted two genes – one from a bacterium, the other from corn — which causes beta-carotene to be synthesized in the edible part of the plant as well. Given its ability to prevent VAD, Golden Rice could make contributions to human health on a par with the Salk polio vaccine.

Plant scientists Ingo Potrykus (l) and Peter Beyer, the inventors of Golden Rice, at the time of the first field trials in 2004 at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. (Golden Rice Humanitarian Board)

But irrational, self-interested, relentless opposition to the testing and widespread availability of Golden Rice has been high on the agenda of activists. The most prominent of them is Greenpeace, a wealthy and evil behemoth with offices in more than 40 countries, and whose PR machine is focused on denying millions of children in the poorest nations the essential food nutrients they need to stave off blindness and death.

Why Golden Rice is not yet globally available

Soon after the Golden Rice prototype was announced, influential food author Michael Pollan wrote an article in the New York Times Magazine criticizing Golden Rice as a kind of Trojan Horse — a way for agricultural biotechnology companies to “win an argument rather than solve a public-health problem.” He and other misguided critics of biotechnology have aggressively promoted many of the criticisms voiced by anti-genetic engineering activist groups, creating simplistic, disingenuous memes that ricocheted across the internet. Here is one example:

Greenpeace has emerged as the most prominent and vocal opponent of Golden Rice. Working with allies in the biotechnology-rejectionist community, it has intimidated government officials and fomented grassroots opposition to regulatory approvals of genetically engineered crop varieties. Too often, regulators have dragged their feet or capitulated.

Greenpeace has fiercely opposed genetic engineering applied to agriculture from the early days of molecular genetic engineering — recombinant DNA technology — to produce so-called “GMOs,” or “genetically modified organisms.” (We prefer, instead, the terms “GE,” or “genetically engineered organisms,” which has less of a public stigma.) Its opposition reaches back to 1995, when the organization announced that it had “intercepted a package containing rice seed genetically manipulated to produce a toxic insecticide, as it was being exported . . . [and] swapped the genetically manipulated seed with normal rice.” [I. Meister, “Uncontrolled Trade in Genetically Manipulated Products,” press release, April 7, 1995].

The rice seeds genetically improved for insect resistance that were stolen by Greenpeace were en route from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich to the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. The engineered seeds were to be tested to confirm that they would grow and produce high yields of rice with far fewer applications of chemical pesticides.

Greenpeace has ignored the broad and longstanding scientific consensus about the safety of genetically engineered crops, the result of thousands of risk-assessment experiments and extensive real-world experience. In the United States alone, more than 90 percent of all corn, soy, and sugar beets are genetically engineered, and in decades of consumption of trillions of servings of food from genetically engineered plants around the world, not a single health or environmental problem has been documented.

Greenpeace opposition grounded in pseudo-science and ideology

Greenpeace’s opposition is grounded in misrepresentations of science. It has long claimed that GE crops are inherently dangerous and unpredictable because the process uses ‘foreign’ genes — obtained from a harmless bacterium from another species — to facilitate the modification.

Greenpeace depiction of GE corn

When scientists devised a way to modify seeds without using heterologous (non-native) genes — a process known as gene editing, with CRISPR, introduced in 2013, being the headline example — Greenpeace switched gears. It now claims that all genetic engineering is dangerous because it turns food production into a “genetic engineering experiment with unknown, potentially irrevocable outcomes.” CRISPR, its recent manifesto states, will “exacerbate the negative effects of industrial farming on nature” — an absurd, insupportable assertion. (The author of Greenpeace’s recent manifesto and head of its Science Unit? A university philosophy major.)

Greenpeace has also attacked the product's effectiveness, alleging that the beta-carotene levels in Golden Rice are too low to be effective or so high that they would be toxic. But feeding trials have shown the rice to be highly effective in preventing VAD, and toxicity is virtually impossible because the conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A in the body is regulated and ceases when vitamin A levels in the blood rise above normal.

With no rational basis for its antagonism, the organization has been forced to adopt a cynical “fake news” strategy of trying to scare off the developing nations that are considering adopting the lifesaving products. In a 2012 screed, for example, Greenpeace falsely claimed, “If introduced on a large scale, Golden Rice can exacerbate malnutrition and ultimately undermine food security.” Psychiatrists call this projection: The real threat to the poor and vulnerable is not genetic engineering; it is Greenpeace and its ilk.

In 2014, agricultural economists Justus Wesseler and David Zilberman calculated the impact of the delays in the regulatory approval of Golden Rice. They reported that the absence of Golden Rice caused the loss of about 1.4 million life-years over the previous decade in India alone. A decade later, the toll has continued to mount.

The story of Golden Rice, which first potentially became available in 2000, is a long and tortuous tale, involving almost two decades of trials and tribulations. But by the mid-teens, after many years of field trials (which have sometimes been vandalized or destroyed by anti-genetic engineering activists, including Greenpeace), the rice was ready for mass rollout. Only Greenpeace and its activist fellow travelers stood in its way.

In 2016, more than 150 Nobel Laureates sent an open letter to Greenpeace, the UN, and others, citing the potential of Golden Rice to improve health outcomes for the poor and the importance generally of genetically engineered crops to improve crop yields, boost farmers’ livelihoods, and reduce environmental impact through less use of chemical inputs.

Gradually, finally, the logjam broke. In 2021, the Philippines became the first country to officially sanction the commercial cultivation of Golden Rice. Cultivation then screeched to a stop in April of this year, when a court backed a Greenpeace petition to block the commercialization of Golden Rice in that country. The effect of this court decision has reverberated across the globe. Scientists from food-insecure nations such as India and Bangladesh fear that the pathway to commercial approval of important genetically engineered crops in their own countries will be more difficult than ever since this latest setback. The consequences will be felt most acutely by the poor, with potentially 100,000 new deaths of children each year as the outcome.

Dangers of ‘precautionary science’

The April decision to revoke that approval was based on the dubious and often weaponized “Precautionary Principle.” There is no widely accepted definition of this “principle,” but in its most common formulation, governments should implement regulatory measures to prevent or restrict actions that raise even conjectural risks of harm to human health or the environment, even though there may be incomplete scientific evidence as to the potential significance of these dangers. It is silent on how much evidence is necessary to prove a negative – that is, the absence of risk.

Use of the Precautionary Principle is sometimes represented as “erring on the side of safety,” or “better safe than sorry” — the idea being that the failure to regulate risky activities sufficiently could result in severe harm to human health or the environment, and that “overregulation” causes little or no harm. Brandishing the bogus “principle,” environmental groups have prevailed upon governments in recent decades to assail the chemical, food, agricultural, nuclear power, and other industries.

Potential risks should, of course, be taken into consideration before proceeding with any new activity or product, whether it is the siting of a power plant or the introduction of a new drug into medical practice. However, the Precautionary Principle focuses solely on the possibility that technologies could pose unique, extreme, or unmanageable risks, even after considerable testing has already been conducted.

What is missing from precautionary calculus is an acknowledgment that even when technologies introduce new risks, many confer far superior net benefits — that is, their use reduces many other, often far more serious, hazards. Examples include blood transfusions, organ transplants, and automobile airbags, all of which offer immense benefits and only minimal risk.

As is its wont, Greenpeace misled the court with factually unsupported precautionary concerns about Golden Rice. Scientists defended the lifesaving grain, but as independent academics — no corporations were involved in the financing or development of Golden Rice — they lacked Greenpeace's lobbying resources and public exposure of Greenpeace.

The recent court ruling in the Philippines is a double whammy for the world’s poorest people, who lack political empowerment and cannot defend themselves against Greenpeace's mendacious rantings. It has reverberated throughout Bangladesh, India, and other food-insecure nations. These countries were seriously considering Golden Rice as a next step to improve their food and agriculture programs, but they might now experience a backlash similar to that in the Philippines.

The cynical “success” of Greenpeace illustrates how frail and tenuous are the world’s regulatory systems for genetic engineering technologies, and how easily they can be attacked and corrupted. The demonization of genetically engineered crops continues, and the poorest of the poor suffer most.

Kathleen L. Hefferon is an instructor in microbiology at Cornell University. Find Kathleen on X @KHefferon

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger distinguished fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. He was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology. Find Henry on X @HenryIMiller