It is hard to explain one’s pain and equally challenging to describe in academic literature. Unfortunately, the numbers used to quantify both are given an unearned certainty. As a result, we have a built-in, imprecise handle on pain and its management.

Nowhere is this better detailed than in a new study in the journal Addiction that looks at opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP). More specifically, they wanted to consider problematic pharmaceutical opioid use, POU, which really means the issues surrounding the legitimate use of pain medications in treating the majority of pain patients. To be absolutely clear, we are not considering acute pain management or end-of-life care. Nor are we discussing the far more deadly use of illicit opioid use, which is far and away the primary source of all drug deaths.

The researchers begin with this premise:

“Clinicians and policymakers need to have accurate estimates showing that the prevalence of POU in CNCP as POU, including opioid dependence and opioid use disorder, is associated with significant harms to individuals, families, and society and is a huge public health burden.”

There is an assumption here that opioid dependence, in the setting of chronic pain management, is associated with significant harm, which is presented as a given and reflects an underlying bias.

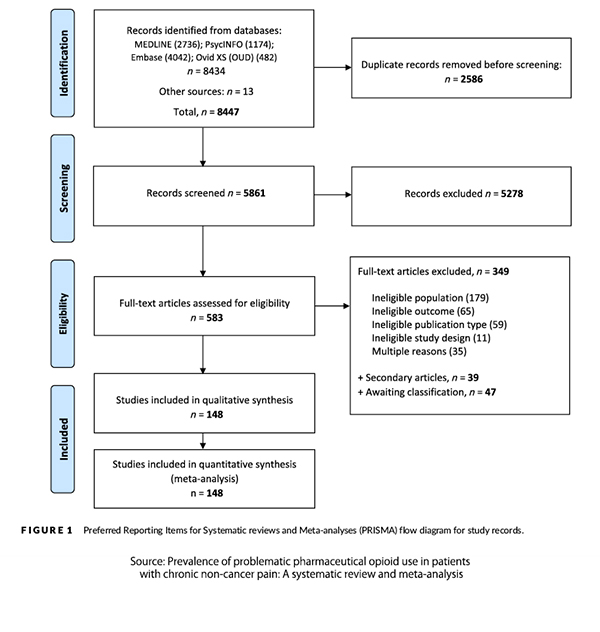

The researchers pointed out that studies of POU demonstrate a very wide range of prevalence, from 0 to 80%, primarily because of “the inconsistency in defining POU with the use of multiple definitions and terminology.” They considered 148 studies involving a cumulative 4.3 million participants to tease out those inconsistencies.

- Fifty-four studies were conducted in pain clinics, 28 in primary care, and 23 in registry/database studies.

- Overall, 4,301,910 participants were included, with study size ranging from 15 to 2,304,181.

- One hundred and nine (74%) studies were classified as having a low risk of bias, with 25% being at moderate risk of bias and 1% being classified as having a high risk of bias. Most studies classified as moderate or high risk of bias did not have a sample representative of the national population, did not use an acceptable case definition, did not use a study instrument shown to have validity and reliability, and did not report an appropriate measure of the prevalence period for the parameter of interest (duration of chronic pain).

As expected, the choice of diagnostic tool was the strongest predictor of prevalence. Using ICD codes, essential for billing with precise requirements, showed the lowest prevalence at approximately 3%. Using the criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Studies Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), there was a four-fold increase from DSM-III’s prevalence (9.9%) and DSM-V’s of 36.7%. While the casual reader might conclude that problematic opioid usage was rising at a tremendous rate, those who are more informed would recognize that the more current DSM-V definition incorporates several previous definitions, melding substance abuse disorder and substance dependence into one category and that the definition of dependence changed.

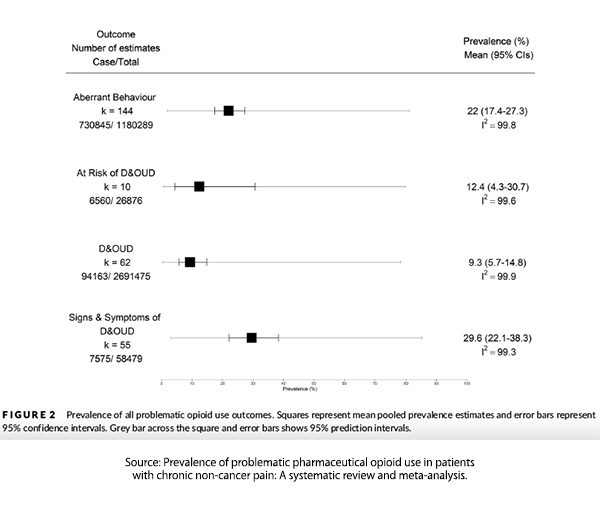

When the goal post for POU was changed to consider any signs or symptoms rather than a coherent cluster of symptoms that might reflect a more accurate picture, the prevalence rose to 29.6%. Aberrant behavior, by itself, reflected a prevalence rose to 22%.

“The prevalence of POU is high with almost one in 10 people identified as D&OUD using diagnostic criteria or at risk of D&OUD, one in three showing S&S of D&OUD and one in five showing aberrant behaviour.”

We must know the more precise estimate because our response should consider whether we are describing 10 or 30 out of a hundred patients.

The researchers freely acknowledge the limitations of their research. The evidence comes from North America and other high-income countries; this may not be a problem for middle- or low-income countries. More importantly, regarding these particular findings, one study contributed more than half of the entire sample.

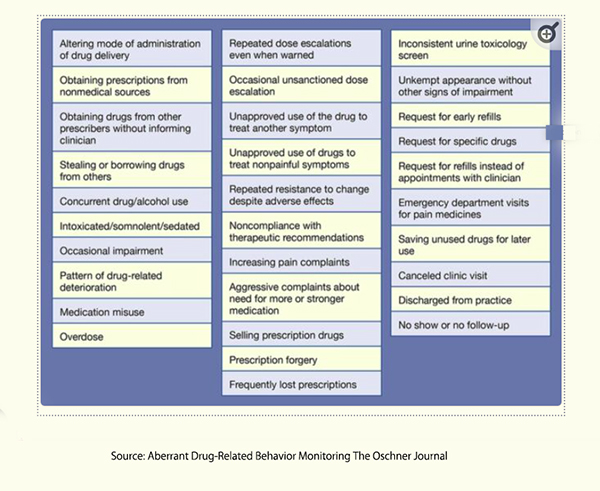

A closer examination of the DSM-V criteria for diagnosing opioid use disorder [1] reveals that these criteria reflect behaviors, and the underlying intent for those behaviors may be more related to circumstances other than to opioid use itself. On the left is a graphic of aberrant behavior defined by the Oschner Clinic.

A closer examination of the DSM-V criteria for diagnosing opioid use disorder [1] reveals that these criteria reflect behaviors, and the underlying intent for those behaviors may be more related to circumstances other than to opioid use itself. On the left is a graphic of aberrant behavior defined by the Oschner Clinic.

While some aberrant behavior may reflect anti-social behavior, e.g., stealing or borrowing drugs from others or prescription forgery, can the same be said for unkempt appearances, canceled appointments, or no-shows? As the researchers note:

“Although aberrant behaviours may indicate a problematic relationship with prescription opioids, other contextual factors may influence the likelihood of these behaviours….early refills or multiple prescriptions, may be indicative of inadequate pain control.”

To be sure, those advocating even tighter controls of opioids in pain management will cite those prevalence estimates based on signs and symptoms, including aberrant behavior. While they may well understand the nuance and uncertainty of their citations, they are counting on their halo of expertise to prevent further inquiry into just what they are reporting. Our regulatory agencies fall short by not conducting due diligence or cherry-picking selective data in the reports they authorize. This issue can be addressed by appointing committees that reflect diverse views and are committed to developing a consensus. Our legislatures fail us by not properly overseeing the work and culture of the regulators they fund.

The nuances of opioid dependence, particularly within the context of chronic pain management, illustrate the intricate interplay between patient behaviors and clinical interpretations. The behaviors often labeled as aberrant may be driven by factors other than addiction, such as inadequate pain management, psychological stressors, or other underlying conditions. This complexity necessitates a careful, individualized approach, considering each patient's unique context and circumstances. Laws and regulations, improperly based upon mandates, are inappropriate, artificially creating certainties when, in truth, much remains uncertain.

Policymakers and clinicians must navigate the fine line between controlling misuse and ensuring adequate pain relief, avoiding the pitfalls of over-reliance on broad prevalence estimates that do not reflect the actual landscape of opioid use in diverse populations. By understanding the limitations and biases inherent in current assessments and fostering collaboration among diverse stakeholders, we can work towards more effective, patient-centered solutions that balance the need for opioid regulation with the imperative to alleviate suffering.

[1] DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

- Opioids are often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use opioids

- Continued opioid use, despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Recurrent opioid use in situations in which it is physically hazardous

- Continued opioid use, despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to be caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Tolerance and withdrawal are not considered salient concerns in those taking opioids under medical supervision for the purposes of this diagnosis.

Source: Prevalence of problematic pharmaceutical opioid use in patients with chronic non-cancer pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16616