Is it possible to snack our way to health? It seems so, but fair warning, these are not snacks we eat. Today’s study concerns exercise snacking, a term with origins at least back to 2007. Based on high-intensity interval training, exercise snacks involve “performing brief isolated bouts of vigorous exercise over the day,” allowing exercise to be integrated into your day instead of a regimented block of time. The term entered the peer-reviewed literature about a decade later, with a study showing that small exercise blocks could promote better glycemic control in patients with abnormal glucose metabolism. Exercise snacking is part of what other researchers have called VILPA, or “vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity” performed as part of our daily living.

Getting with the Guidelines Is Nice If You Have The Time

The guidelines for physical activity, based primarily on data obtained from participant surveys of activity, recommend

“150–300 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), 75–150 min of vigorous physical activity (VPA), or a combination of both a week.” [1]

For those trying to achieve those goals at the neighborhood gym, we are talking about at least an hour every day (including getting to and from the gym, changing clothes, and washing up). The time for those with a home gym may be a bit less, but that time commitment is a significant hurdle. Let’s be honest: that hurdle and being motivated enough to go from couch potato to gym rat may be one hurdle too many.

Over the last few years, those guidelines have moved the goalposts by emphasizing the value of shorter exercise intervals, but not so short as an exercise snack – roughly less than 2 or 3 minutes. A study reported in the European Heart Journal tries to better quantify the portion control for exercise snacking.

Tech helps to separate Gym Rats from Snackers

Unlike the prior studies, which generated those necessary exercise minutes, this study used accelerometers rather than surveys. The advantage was a more accurate measure of activity than the potentially biased self-reports of exercise. However, while providing quantifiable information, the accelerometers only caught a 7-day moment. To ascribe the greatest certainty to the study, one must assume that that one-week snapshot represented activity long before and after the measurements. The participants were 103,000 adults aged 40-69 from our old friend, the UK Biobank. To get at the necessary dose of exercise that would be most beneficial, the researchers combined the accelerometer data, lifestyle characteristics [2], and data on the incidence and mortality from cancer and cardiovascular disease over a 6-year interval.

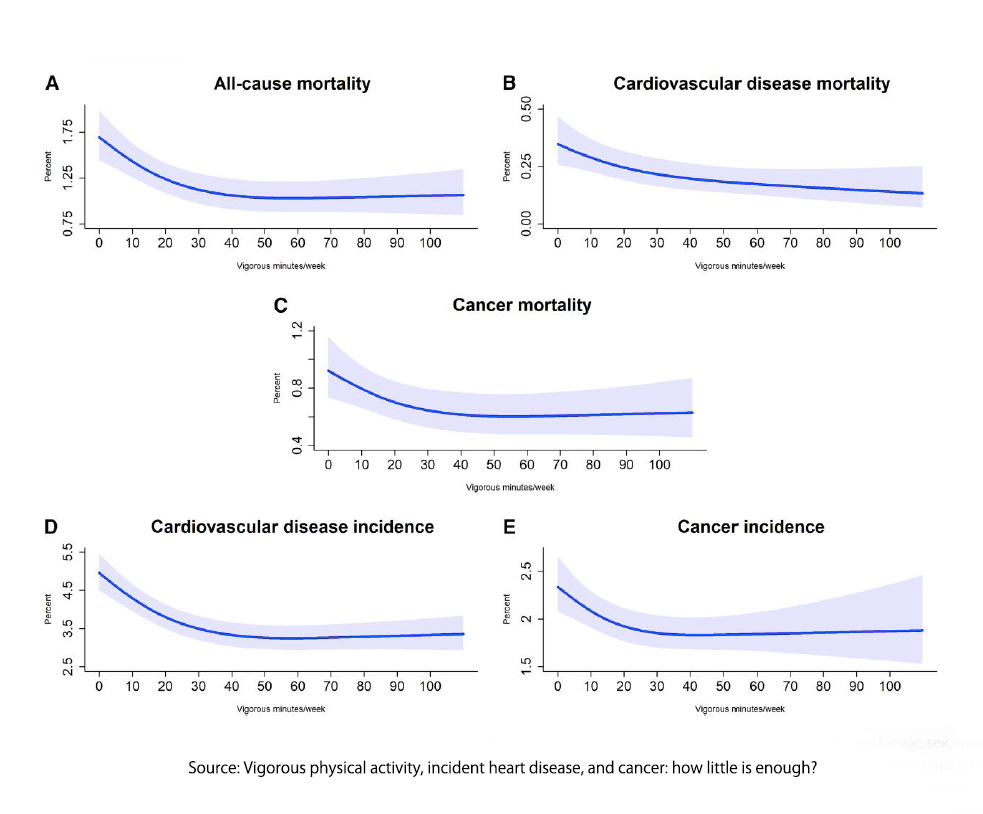

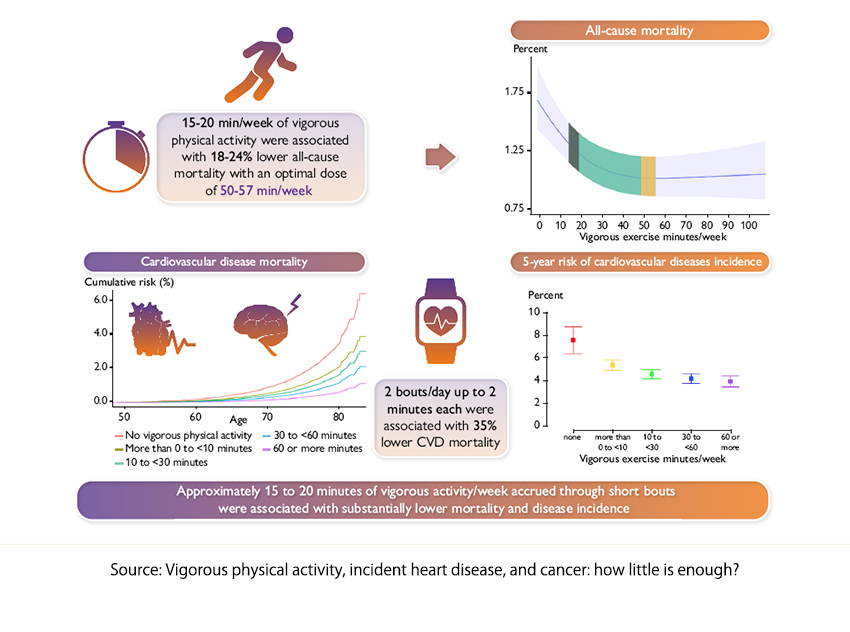

The data in its rawest form shows a relatively steep drop in mortality and incidence over roughly the first 40 minutes of weekly vigorous physical activity (VPA) in intervals of 2 minutes. As the researchers write:

“Our dose-response curves for all three mortality outcomes suggested that levels well under the current recommended 75 min/week of VPA were associated with the lowest risk. … Regarding minimum dose, ∼15 min/week was associated with a 16– 18% lower all-cause and cancer mortality risk, and 20 min/week was associated with a 40% lower CVD mortality risk.”

In other terms, two 2-minute bouts of VPA daily reduced the incidence of cardiovascular disease by 35% and cancer by roughly 16%. The differences may concern the more significant effect of diet on cardiovascular disease. Increasing those 2-minute intervals to four a day reduces overall mortality by 27%.

Debunking the Myth of Activity being separate from lifestyle

There are several noteworthy points to unpack. First, there is a marked difference in the amount of time spent in VPA felt to reduce risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer between this study and the guidelines. By the researchers’ calculation, a three-fold reduction. That doesn’t mean that the initial research was wrong; it reflects a very different measure of activity. Self-reported exercise can be uncertain because of our memories, the bias we may feel in how strenuous the activity is, and to be fair, a biasing need to look good even when assured the data collected is anonymous. Unless you strap them onto your dog rather than your wrist, accelerometers will be far more accurate in quantifying your exertions throughout the day. Conflicting data may, at its root, more often reflect differing measurement methodologies.

“Our findings suggest that short VPA bouts may be also embedded into regular activities of daily living and accrued intermittently throughout a week. The VPA volume doses we identified as potentially beneficial were consistent across age, sex, and many lifestyle and health risk factors.”

From a public health point of view, stressing the value of short bursts of activity readily incorporated into your day may overcome some of the hurdles in becoming more active. A brisk walk or a few minutes of stair-climbing are readily available for more than a gym trip or the cost of fitness equipment for our homes. Exercise snacking is a more practical application of generic health advice to a much larger population.

In a world where time is precious, exercise snacking offers a practical and effective alternative to traditional workout routines. By integrating short bursts of vigorous activity into your daily life, you may reap significant health benefits without setting aside time to exercise.

[1] VPA, vigorous physical activity is equivalent to at least six metabolic equivalents (METs), e.g., rapidly climbing two flights of stairs, same for a short but brisk walk.

[2] Among the variables are age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, sleep quality, screen time, family history of cardiovascular disease or cancer, and current use of cholesterol, blood pressure, or diabetes medications.

Source: Vigorous physical activity, incident heart disease, and cancer: how little is enough? European Heart Journal DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/626.

Exercise Snacks: A Novel Strategy to Improve Cardiometabolic Health Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews DOI: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000275