If you grew up in the middle of the early AIDS epidemic as I did, something I've written about firsthand, the results of a study on a twice-yearly injection from Gilead seem almost too good to be true.

Over the past four decades, the progress against HIV/AIDS has been nothing short of miraculous. Here's a quick look at the taming of a death sentence by the discovery and use of better and better drugs.

- 1980s: The first published report of AIDS infections by the CDC in 1981. AZT (zidovudine) becomes the first FDA-approved drug for AIDS. But it is toxic and ineffective.

- 1990s: Major turning point with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996, reducing AIDS-related deaths for the first time. However, the pill burden is oppressive; patients must take up to 40 pills per day at regular intervals. The combination therapy is effective, but the side effects could be brutal.

- 2000s: More efficacious and less toxic antiretroviral drugs, sometimes combined in one pill, improve patient compliance, outcomes, and quality of life. First progress in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. AIDS becomes a manageable chronic condition.

- 2010s: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drugs prevent transmission of the virus.

Another major milestone. And then some.

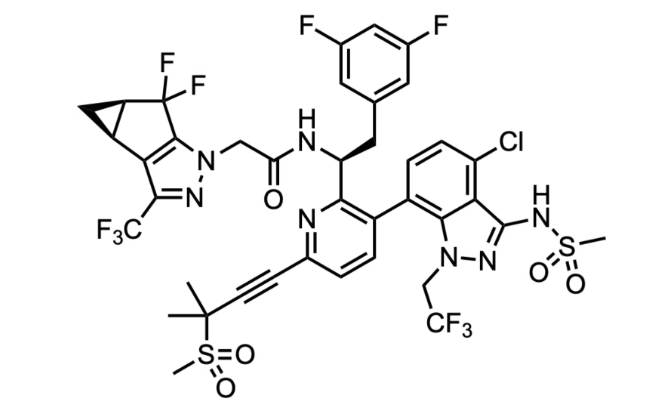

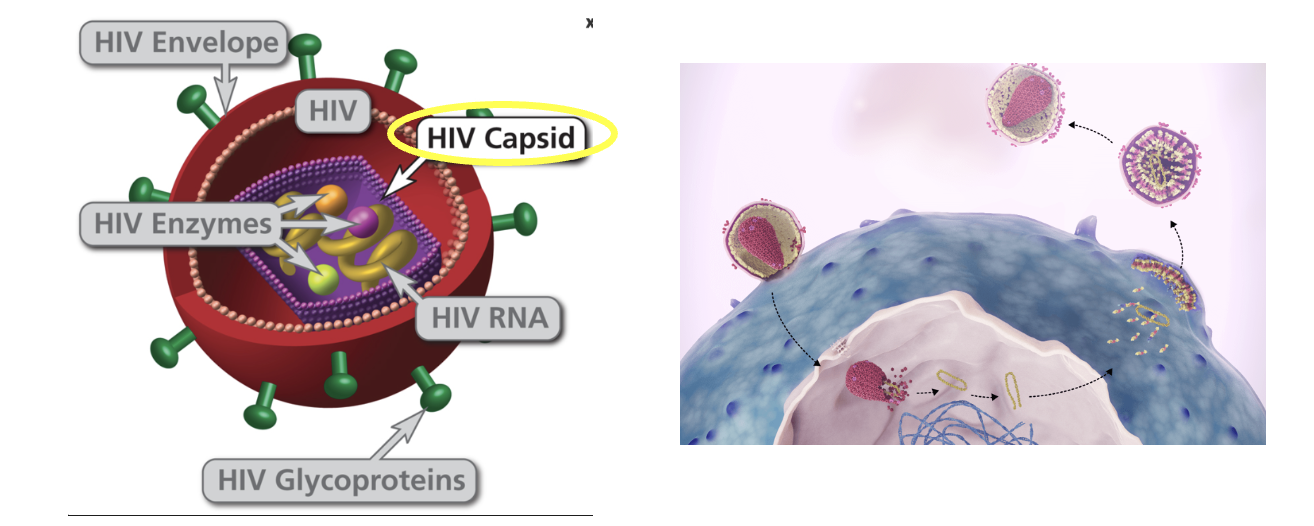

A June 20th press release from Gilead Sciences Inc. summarized the results of the company's PURPOSE 1 trial, which examined the efficacy of injectable lenacapavir (Sunlenca) in Sub-Saharan Africa, where women and adolescent girls make up almost 60% of all new HIV infections globally. Although PrEP drugs would have prevented most (1) of these infections, access and adherence to a regular schedule were sometimes problematic, especially in Africa.

The PURPOSE 1 trial, a Phase 3, double-blind, randomized study that began in 2021, evaluated the efficacy of lenacapavir – a capsid inhibitor – given by subcutaneous injection twice per year (!) against two commonly used PrEP drugs, Truvada and Descovy, both nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (2). The results were astounding:

- 5,300 female study participants, aged 16-25, across 25 sites in South Africa and Uganda

- 2,134 received lenacapavir (two injections per year)

- 1,068 received Truvada (one pill per day)

- 2,136 received Descovy (one pill per day)

- 16 of the 1,068 women (1.5%) of the women who took Truvada became infected

- 39 of the 2,136 women who received Descovy (1.8%) became infected

- There were ZERO infections in the 2,134 women who received the lenacapavir injections

If someone projected this back in the early 1990s when people were dying miserable (and inevitable) deaths, I would have suggested a psych evaluation. (When preliminary results became available, the trial was stopped early, and all the women switched to lenacapavir.)

The first capsid inhibitors

NOTES:

(1) Truvada, when used as directed, is about 99% effective in preventing transmission.

(2) Because effective PrEP options already exist, there is broad consensus in the AIDS field that using a placebo group would be unethical. I fully agree.

(3) HIV protease inhibitors also block maturation, but by a different mechanism. Lenacapavir does not inhibit HIV protease.

(4) Lenacapavir does not inhibit HIV polymerases; it indirectly inhibits their action by a mechanism that is different from NRTs and NNRTs.