“Studies have not rigorously investigated associations between opioids administered in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting during mechanical ventilation and posthospitalization opioid use.”

The war on opioids in medicine has found a new target: opioid use during mechanical ventilation – when a machine does the breathing for you. Mechanical ventilation, being put on “the vent,” may be known to the general public from its association with the critically ill during the COVID pandemic. In general, opioids are used for “comfort care” to alleviate any pain, to reduce the discomfort of having a tube connecting you to the ventilator in your throat (Think of a constant gag reflex), and as an adjunct in sedating the patient.

The study involved adult patients admitted to the medical ICU at one of Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California networks requiring mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure. The researcher took pains to reduce the study group to those with a medical cause of respiratory failure and who were not destined for chronic ventilator care.

The study’s “variable” was the amount of intravenous fentanyl received by patients while on the ventilator. The amount of fentanyl received was based on the pharmacy records, and when another opioid was used, it was converted to “fentanyl equivalents.” The study’s primary outcome was the “first filled opioid prescription in the year after discharge;” secondary outcomes include a subsequent diagnosis of “opioid-related use, abuse, or overdose… any opioid prescription filled in the 30 days after discharge, and persistent opioid use over 1 year.”

From roughly 74,000 patients, 6,800 were included in the study, with slightly more males than females with a median age of 67. 12.5% self-identified as Black, approximately 14% as Asian or Hispanic, and 52% as White. The tercile (thirds) breakdown of patients used 0-67 μg, 68 to 700 μg, or more than 700 μg of fentanyl equivalents while being mechanically ventilated.

“A total of 2942 patients (43.6%) experienced the primary outcome of a filled opioid prescription in the 1 year after discharge, of whom 353 (12.0%) were in the reference group, 741 (25.2%) were in tercile 1, 879 (29.9%) were in tercile 2, and 969 (32.9%) were in tercile 3.”

Nearly half required a post-discharge opioid prescription, and from a cursory view of the data, that need increased as the total fentanyl equivalents rose – an escalating dose response. There was a similar dose response to the secondary, “,” with the notable exception of opioid-related use, abuse, or overdose that did not achieve statistical significance.

This lead the researchers to conclude

“Higher doses of opioids during mechanical ventilation were also associated with persistent opioid use after hospitalization.”

That, of course, raises the concern that our best efforts at care are creating more opioid-addicted individuals.

Shoddy work

This study has several significant problems; let me point to two. First, there is a misleading context presented early in the paper.

“First, critical care practice guidelines recommend high-potency intravenous opioids as the first-line sedatives for discomfort during mechanical ventilation for critically ill patients.”

If you look at the guidelines they cite in making that statement [1], opioids are not the guidelines for sedation; “nonbenzodiazepine sedatives” are the recommended choice. Pain medications are for treating pain. That Kaiser Permanente Northern California chooses to ignore the guidelines is a matter of medical judgment. That they mislead the reader who is not fully conversant with the current recommendations is problematic. Problematic, too, is that a peer review failed to identify that misleading statement.

The second is a bit of Mathmagic or perhaps faulty thinking. Harken back to this result of the study cohort after mechanical ventilation.

“A total of 2942 patients (43.6%) experienced the primary outcome of a filled opioid prescription in the 1 year after discharge.”

It needs to be tempered by this much earlier description of the study group.

“Of the participants, 3114 (46.2%) filled an opioid prescription in the year prior to admission.”

That might suggest that if 46% were using opioids before admission and 43% were using them afterward, the opioid use associated with mechanical ventilation reduced opioid dependency. Stating that opioid use persisted after discharge to imply opioid’s harmful impact is the same type of logic we get from politicians who see an absolute rise in spending as a cut.

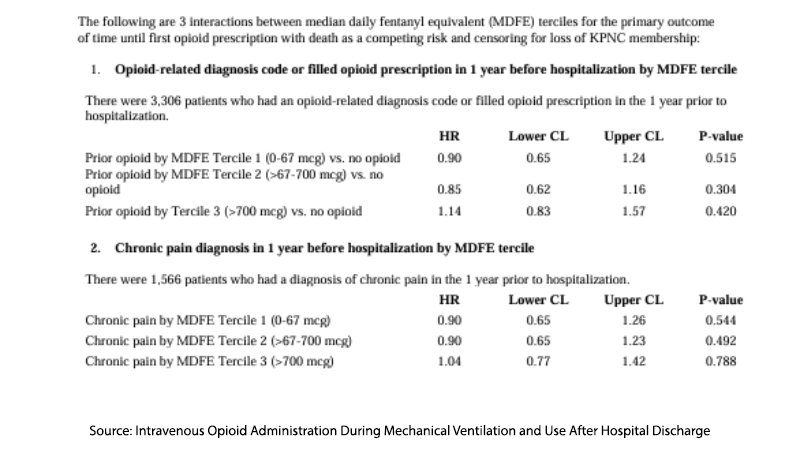

A careful review of the differences in the lowest and highest tercile in terms of their opioid use before admission suggests that there are pertinent differences between them, not solely based on how many fentanyl equivalents they received. 21% more patients in the highest tercile had a history of chronic pain than those in the first tercile. 15% more in the highest tercile had at least one opioid prescription filled prior to hospitalization than the first tercile. Are these groups the same, similar, or apples and oranges?

Go to the supplemental information and look at the stratification based on prior opioid use. You will see that the elevated risk from higher fentanyl equivalents during mechanical ventilation greatly diminishes, to the point that they are not statistically, and I would argue clinically significant.

It is unclear whether the misdirection in reporting the findings lies solely with the authors; that makes the role of peer review more a rubber stamp than a quality check. As to intent, I fall back upon my current favorite phrase, Hanlon’s Razor,

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

Some might argue that this is just a filler study, having, at this moment, been read online by about 1000 and not yet used as a citation in other works. But that might change, and we will discover this flawed paper being cited in different studies. After all, the researchers are expressing, even in a tentative way, the need to take opioids out of ventilator management.

“Taken together, these findings suggest that exposure to opioid during mechanical ventilation, which may be modifiable, may influence patients’ opioid use in the long term…. Understanding the mechanisms that underlie tolerance and dependence may inform the development of reversal drugs and/or raise awareness that compels clinicians to further change their prescribing behaviors.” [emphasis added]

While the study attempts to highlight a potential link between opioid use during mechanical ventilation and long-term opioid dependence, its flawed methodology and misleading presentation of data undermine its findings. By not adequately accounting for pre-existing opioid use and other confounding factors, the study falls short of providing a clear causal relationship.

[1] “We recommend that intravenous (IV) opioids be considered as the first-line drug class of choice to treat non-neuropathic pain in critically ill patients. … We suggest that sedation strategies using nonbenzodiazepine sedatives (either propofol or dexmedetomidine) may be preferred over sedation with benzodiazepines (either midazolam or lorazepam) to improve clinical outcomes in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients” – Critical Care Medicine Guidelines

Source: Intravenous Opioid Administration During Mechanical Ventilation and Use After Hospital Discharge JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.17292