Have you noticed that the television weather is no longer content to report and predict but has taken to catastrophizing the changing climate? No longer are there heat waves, but we are told how many millions are “at risk.” The current rising temperatures in our Southwest were not only a cause of alarm for our changing climate but put “18 million” at risk for heat stroke. And if that was not sufficiently concerning, Maricopa County had recorded over 645 heat-associated deaths this past year.

Let’s talk about those numbers, but first, heat-associated deaths.

Heat-associated deaths, let’s break it down

Heat-associated includes two somewhat ambiguous categories. First, deaths related to heat are subjective opinions expressed on a death certificate indicating that high temperatures contributed to the individual’s death. It is reminiscent of the heated discussions concerning death from or with COVID-19. As I said at the time, death certificates are the story we tell, and without autopsies, they may sometimes be more fanciful than factual.

The second category of death, from heatstroke, has few objective and discriminating features. The diagnosis of heatstroke remains primarily clinically based on the presence of

- An elevated temperature (hyperthermia)[1]

- Alterations in an individual’s neurologic status

- A recent exposure to hot weather or physical exertion

Heatstroke can be further categorized as classical and exertional. Classic heatstroke happens due to environmental heat and inadequate cooling, while exertional heatstroke is caused by intense physical activity, leading to excessive metabolic heat production.

The more typical form of heatstroke often affects the elderly, chronically ill, and those unable to care for themselves, especially during heatwaves. Elderly individuals are particularly vulnerable due to their reduced ability to regulate body temperature. Prepubertal children are also at risk due to a high surface area-to-mass ratio, an underdeveloped thermoregulatory system, small blood volume, and a low sweating rate, all of which impair effective heat dissipation.

Exertional heatstroke is a medical emergency caused by strenuous physical activity. It can affect athletes, laborers, soldiers, and others engaged in intense activities. Unlike classic heatstroke, it doesn't always require high ambient temperatures to occur.

Thermoregulation fails, and our internal heat can’t escape

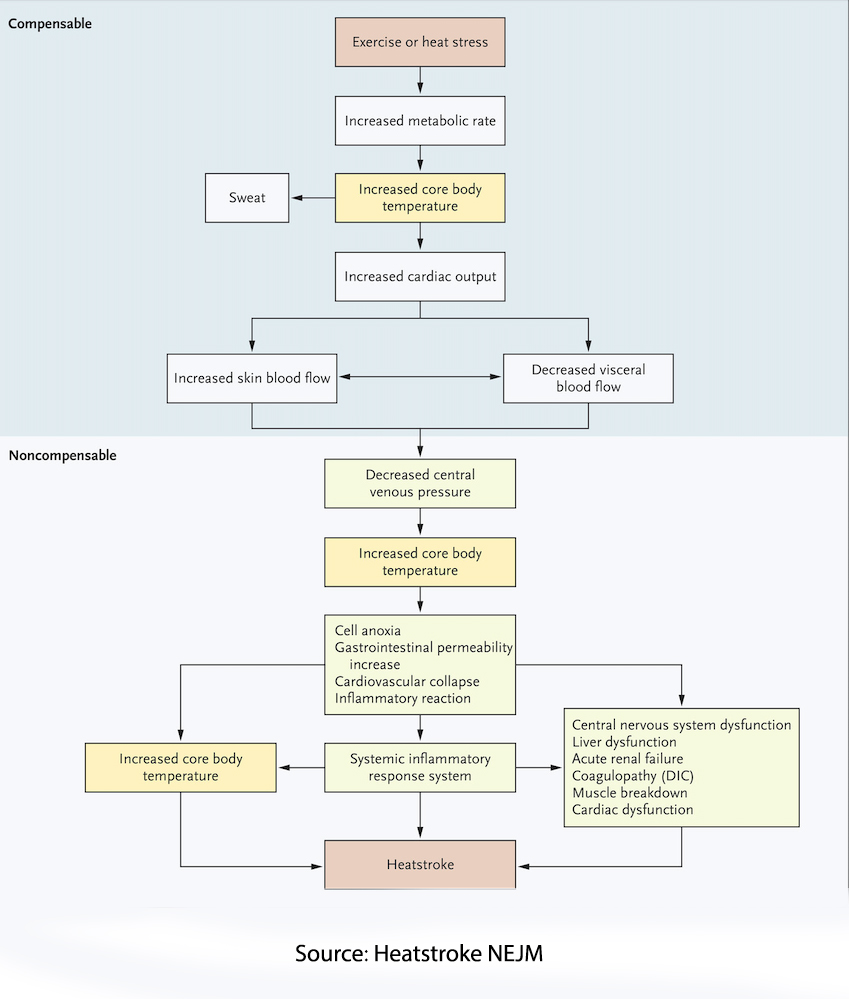

“A person's ability to thermoregulate is closely linked to the ability of the cardiovascular system to cope with central and peripheral blood flow demands to support metabolic and thermoregulatory requirements.”

Thermoregulatory failure means the body can't dissipate heat effectively, leading to high heat storage and a significant rise in core temperature. Sweat production is our primary means of cooling, activated by central temperature receptors or increased skin temperature. The subsequent evaporation of sweat cools the blood passing through our skin and is dependent on the ambient humidity – humid environments make thermoregulation difficult.

To increase the blood flow to the skin, our blood vessels dilate, reducing the volume of blood available for the heart to pump, especially to the kidneys and intestines. When these alterations overcome the ability of the heart to compensate for these changes, there is a spiraling set of problematic outcomes.

Heatstroke-related gastrointestinal ischemia reduces intestinal blood flow, causing cell damage and increased permeability, leading to endotoxemia, the release of endotoxins into the bloodstream. This overwhelms the liver's ability to detoxify the endotoxins, worsening the patient's condition.

The endotoxins, in turn, trigger a coordinated stress response that includes endothelial cells, leukocytes, and epithelial cells working to protect and repair tissues, mediated by heat-shock proteins and cytokines. Among the many inflammatory responses is disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which causes diffuse small clots that can further impair circulation and accelerate a failing inflammatory response. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) is seen in 84% of patients with more severe and deadly exertional heat stroke.

In the earliest acute phase of heatstroke, there can be a range of neurologic changes, from general changes like confusion, agitation, nausea and vomiting, and slurred speech. Seizures may occur in more severe cases with brain swelling and possible long-term injury. The inflammatory alterations begin over the next 24 hours, which can result in DIC and respiratory distress. As the overworked heart fails, it worsens kidney and liver function.

Cool and Run, swift emergent care

In the presence of major trauma, emergency medical personnel are trained to scoop and run, transporting the patient as they simultaneously administer the necessary life-saving care. The prognosis for heatstroke worsens if the core body temperature remains above 40.5°C. Therefore, rapid and effective cooling is crucial. Today, emergency medical personnel will transport hyperthermic patients while initiating life-saving cooling, hence cool and run. [2]

Immersion in cold water is the preferred method for treating exertional heatstroke, achieving a cooling rate of 0.20° to 0.35°C per minute. For elderly persons with classic heatstroke, cold-water immersion can provide an acceptable cooling rate, but the preferred treatment involves conductive or evaporative cooling methods. These methods include infusing cold fluids, applying ice packs or wet gauze sheets, and fanning. Although less efficient than cold-water immersion, they are better tolerated and more accessible during heatstroke epidemics when emergency departments may be overwhelmed. Antipyretic agents like aspirin and acetaminophen are ineffective for heatstroke since they target fever, not hyperthermia. These agents can also worsen coagulopathy and liver injury in heatstroke patients.

Prompt intervention may reverse the underlying pathologic changes, but delays in treatment result in greater and greater long-term neurologic sequelae, e.g., cognitive changes and difficulties with coordinated movement. In the most severe of cases, particularly exertional heatstroke, there is a mortality approaching 25%.

Risk Factors

- Dehydration is a logical risk factor because it lowers the amount of fluid the heart pumps below its optimal level. This results in higher heart rates, lower sweat rates, and less temperature tolerance than hydrated individuals.

- Obesity acts as an insulator, reducing sweat rates and maintaining core temperatures, and is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular fitness necessary to compensate for increasing body temperature.

- Gender is a factor, with the more classical forms of heatstroke seen in women with a smaller surface areas-to-mass ratio and more fat, reducing the capacity to sweat. On the other hand, men are more often victims of exertional hyperthermia because they choose strenuous activities, i.e., football “practice” in the late summer.

- Aging also plays a role. The young are more susceptible to exertional heatstroke because they are more active. At the same time, the elderly have impaired sweating and cardiovascular fitness, which contribute to an impaired response to increased core temperatures.

- Co-morbid illnesses, especially diabetes, can further impair cardiovascular function as well as our immune responses, and underlying gut disease may lower the barrier to the “leaky” gut associated with endotoxemia and SIRS

Preventing heatstroke is more effective and certainly easier than treating it. During warm weather, especially heat waves, it is crucial to take protective steps to mitigate the risk of classic heatstroke. This includes staying in air-conditioned places like homes, shopping malls, or movie theaters. Using fans, taking frequent cool showers, and decreasing physical exertion are essential measures. Increasing social contact can help counteract isolation, which can be particularly dangerous in hot weather. Family members, neighbors, and social workers are advised to frequently check on elderly persons to ensure their well-being.

Experience-based measures at both the individual and organizational levels are critical to preventing exertional heatstroke. These measures include acclimatizing to new environmental conditions and matching physical exertion to one's fitness level. It is also important to avoid training during the hottest parts of the day and to remove clothing that interferes with sweat evaporation. Maintaining a proper hydration regimen and scheduling rest periods during physical activity are also crucial. Additionally, individuals showing early signs of heat illness should be prevented from engaging in physical activity to avoid the onset of exertional heatstroke.

Maricopa County’s deaths, the highest in the land

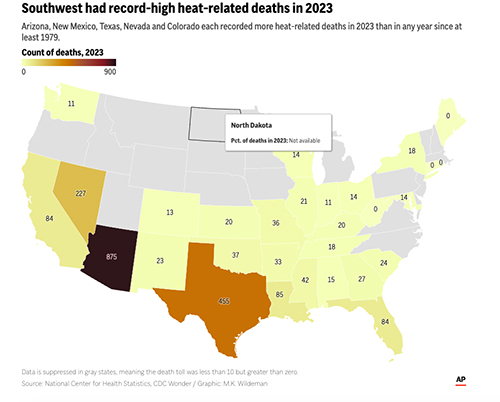

The choice of mentioning those 645 heat-associated deaths in Maricopa County in 2023 was calculated to get your attention. It had the highest rate of heat-associated deaths in the US, as this map from the AP would suggest.

Arizona, Texas, Nevada, Florida, and Louisiana accounted for nearly two-thirds of all these deaths – Maricopa County was responsible for a third of those deaths, so it may reflect being more of an outlier.

It is instructive to look at Maricopa’s statistics informed with hyperthermia’s risk factors.

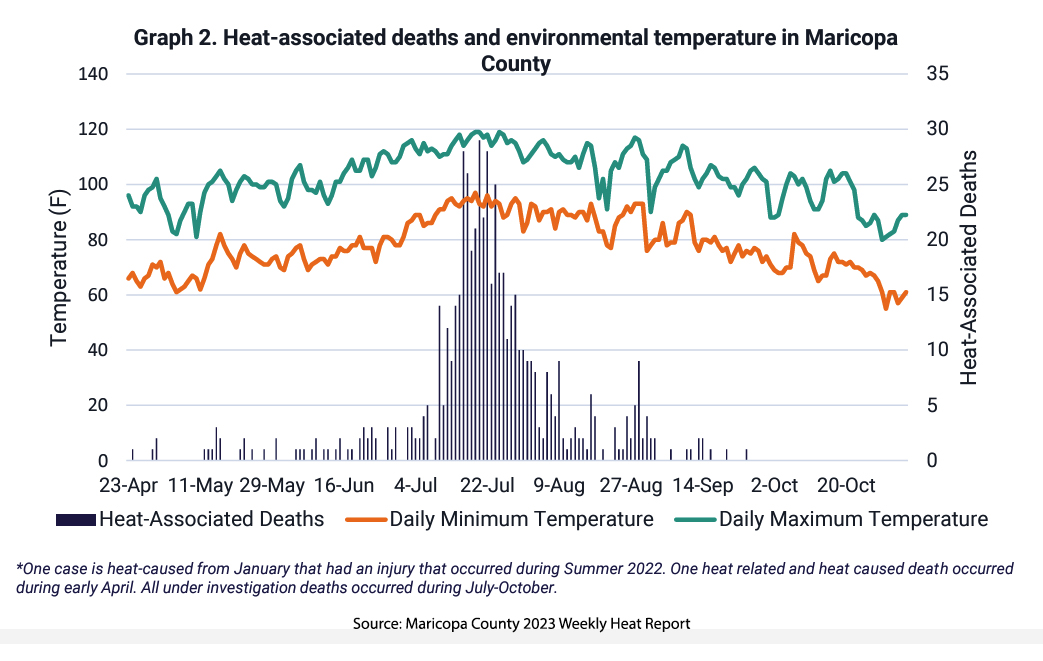

Maricopa County experiences some of the most extreme temperatures in the US. In 2023, there were over 100 days when the temperature was above 100° F

Maricopa County experiences some of the most extreme temperatures in the US. In 2023, there were over 100 days when the temperature was above 100° F

This graphic, taken from a report on Maricopa’s heat-associated deaths, tells an important story. The majority of  cases are from being outdoors. This helps explain why 45% of the deaths are among the homeless. Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services points out that agricultural workers are 35 times more likely to die a heat-associated death than other occupations, although construction is a close second. Moreover, many of these occupationally-related deaths occur within hours of being hospitalized, so they are among the most severe of cases.

cases are from being outdoors. This helps explain why 45% of the deaths are among the homeless. Data from the US Department of Health and Human Services points out that agricultural workers are 35 times more likely to die a heat-associated death than other occupations, although construction is a close second. Moreover, many of these occupationally-related deaths occur within hours of being hospitalized, so they are among the most severe of cases.

A closer look at those indoor deaths reveals that 75% had a non-functioning air conditioner. It is easy to see how social determinants of health, income, housing, and occupation are entangled with the diseases of obesity and diabetes, creating a group of individuals at significant risk when the temperature rises.

Next time you hear about the latest heatwave, take a breath and grab a cool drink. Whether classic or exertional heatstroke, prevention and practical measures are key. Stay cool, stay smart, and let’s leave the drama to the weather channels.

[1] Temperatures greater than 2.5°C from resting values, roughly in the range of 40°C or 104°F

[2] You can read a longer description of cool and run from the NY Times here.

Sources: Extreme Heat US Dept. of Health and Human Services

Maricopa County 2023 Weekly Heat Report

Exertional heat stroke: pathophysiology and risk factors BMJ Medicine DOI: 10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000239

The pathophysiology of heat exposure Temperature DOI: 10.1080/23328940.2015.1051207

Heatstroke NEJM DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1810762