The public wants to be and feel safe. One group has elected progressive prosecutors emphasizing diversion over incarceration, diminishing penalties, and decriminalizing crimes. Other groups have elected more traditional “law-and-order” prosecutors focusing on swift and harsh punishment. A recent study in Criminology and Public Policy looked at how progressive prosecutors “shaped” crime.

What policies reduce crime?

Short answer: we do not know. But progressive vs. law-and-order prosecution suggests at least two separate theories.

Deterrence – swift, sure, and severe punishment shapes “the choice calculation of potential offenders,” reducing future offenses and overall crime. A corollary belief, incapacitation, results in offenders being incarcerated (incapacitated) for more extended periods, keeping streets safer longer. These law-and-order advocates criticize progressive prosecution for sending the wrong message: to criminals, that their offenses will be lenient or they will experience less incapacitation, and to police who will be “demoralized” by the inaction of prosecutors for their efforts at enforcement and arrest.

“Traditional prosecution breaks the people it should protect.”

- Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner

Coercive Mobility – high levels of incarceration and incapacitation “disrupt informal systems responsible for community social organization and stability.” The disruption of family, local economy, and civic participation fuels higher crime rates. Alternatives to incarceration should mitigate its harmful effects and lower crime. Progressive prosecutors also point to clear disparities associated with race and income (caste) in the apprehension of offenders and their subsequent punishment, aligning their theory with the goals of social justice.

A third prominent theory of crime, “the broken-window theory,” comes from a widely quoted and misunderstood article on policing, “Broken Windows. It has led to zero tolerance for panhandling and New York’s “stop and frisk.” But its original goal was fixing the environment rather than pursuing the one who threw the rock. According to this belief, more aligned with progressive prosecution than law-and-order, the impact of prosecution on crime is overstated, and structural forces, “poverty, concentrated disadvantage, residential instability, community demographics are more proximate causes of crime.”

The research sought to understand the impact, if any, of progressive prosecutors in “the nation’s 100 most populous counties” between 2000 and 2020.

The Data

In setting charging and plea policies, progressive prosecutors determine the shape of criminal justice. To generalize, this includes

- Increase the use of diversion, especially for those with mental illness or addiction issues.

- Decriminalize low-level drug possession, de-felonize property crimes by raising the dollar threshold for felony offenses, and rely less on prison for parole violations.

- Minimize harsh sentencing.

- Remove “poverty traps” by reducing court fines and cash bail

- Bolster system integrity with conviction review, broadened discovery, and prosecuting police misconduct.

- Track their performance with data tracking systems.

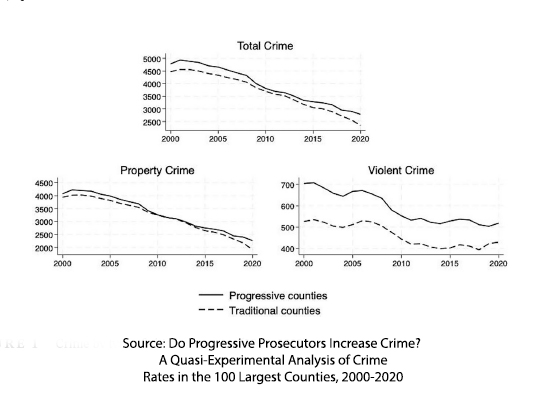

Prosecutors meeting six of these characteristics [1] were considered progressive. Sensitivity analysis showed that broadening or restricting the definition of progressive prosecutor did not impact the study’s results. Progressive prosecutors were identified based on criteria found in both the media and academic publications. By looking at the most populous counties in the US, the researchers identified the top 100 with progressive prosecutors from 2000 to 2020. Crime data came from the FBI’s national Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) and focused on violent crime, property crime, and total index crime rates per 100,000 at the county level, which was a closer match to the area influenced by a given prosecutor.

To estimate the effect of the new progressive prosecutors, the researchers applied difference-in-difference changes in crime rates in the 100 counties of interest compared to similar counties with law-and-order prosecutors. [2]

“Our results show that, relative to jurisdictions that had maintained traditional chief prosecutors, jurisdictions that changed to progressive prosecutors had 7% higher total index crime rates (driven by higher property crime rates), and these effects are strongest from 2013 to 2020. In contrast, violent crime rates were not statistically higher in jurisdictions switching to progressive prosecutors over the entire study period but did experience statistically higher violent crime rates from 2014 to 2016.”

For those in a hurry, counties with progressive prosecutors experienced more property-related crime but no change in violent crime. But there are other insights to be found.

- 70% of jurisdictions have had progressive prosecutors since 2010 - “progressive prosecutors are not a new phenomenon.”

- Counties electing progressive prosecutors did not differ from law-and-order counties on “percentages of residents who were male, Hispanic (of any race), aged 15 to 29, foreign-born, on public assistance, and living in poverty.” They did not differ in median income or home value but did have greater population density and percentages of “non-White” residents. Interestingly, they had higher rates of violent crime before progressive prosecutors were elected.

Crime, which was more significant in those “progressive” counties at the start of the study period, remained greater than for law-and-order counties – but the downward trends were parallel. All three crime measures “dropped considerably in both progressive and traditional jurisdictions.” The difference was in the rate of that decrease.

Crime, which was more significant in those “progressive” counties at the start of the study period, remained greater than for law-and-order counties – but the downward trends were parallel. All three crime measures “dropped considerably in both progressive and traditional jurisdictions.” The difference was in the rate of that decrease.- There is no clear evidence that being soft or hard on crime resulted in significant differences in that downward trend.

- Counties with progressive prosecutors saw a 6.98% relative increase in property crimes; however, they had “no reliable effect on violent crime.”

These increases did not increase significantly over time, suggesting no “anticipation of leniency” among offenders, resulting in more crime. Changes in crime rates also appear to require several years to stabilize, suggesting that “time in office” may play a role for property but not violent crimes.

These increases did not increase significantly over time, suggesting no “anticipation of leniency” among offenders, resulting in more crime. Changes in crime rates also appear to require several years to stabilize, suggesting that “time in office” may play a role for property but not violent crimes.

Returning to the three theories of crime and punishment, the researchers conclude that the data “are most consistent with deterrence theory.” They point out that violent crime is more frequently situation-dependent and that a criminal risk-benefit analysis plays no role. In comparison, non-violent crime may be planned, and some calculus involving lenient or severe punishment is considered.

The study comes with the usual caveats about extrapolation to different-sized populations, the definitions employed, specifically what a progressive prosecutor is, and missing crime data. The weakest link lies in the definition, “…as our coding scheme focuses on stated prosecution policies, not actual practice ... we recognize some policy slippage may exist…” [emphasis added]

From a quantifiable view, progressive prosecutors have not fully realized their goal of decreasing crime. Some would argue that it failed completely. But for those of us who live in these counties and are not policymakers, the question is not really about those quantified findings – whether we are indeed “safer.” The question is whether we “feel” safer.

The daily drumbeat across the media of murders and mayhem contributes to our perception. Rarely does the media discuss property crime, except perhaps in the trend towards “flash mob” theft from luxury goods stores or the robbery that turns into a mugging or murder. As a result, we may not believe the numbers. Our policies on criminal enforcement should not be captive to the numbers or our feelings. The current media debate about soft-on-crime prosecutors and cash-less bail would be better served if we balanced our fears with facts – including this study's findings.

[1] Characteristics of Progressive Prosecutors included self-proclamation, “smart” data collection and tracking, reductions in mass incarceration, removal of poverty traps (bail), alternatives to criminal intervention, decriminalization of youthful offenders, reduction in harsh penalties, reduction in racial and other disparities and increasing system integrity which would include prosecuting police misconduct, broadening discovery and expanding and sealing of records.

[2] Difference-in-difference analysis requires several assumptions. The requirement that a progressive prosecutor was present throughout the period studied was met, as was the need for consistent crime data. The parallel downward trend for all crimes in all jurisdictions to decrease strongly suggests that the final two required assumptions, that there was limited anticipation of change, “no causal effect before its implementation,” and that “counties eventually treated [with a progressive prosecutor] would have had similar crime trends if not for exposure to the treatment” were met.

Source: Do Progressive Prosecutors Increase Crime? A Quasi-Experimental Analysis of Crime

Rates in the 100 Largest Counties, 2000-2020 Criminology& Public Policy DOI: 10.1111/1745-9133.12666