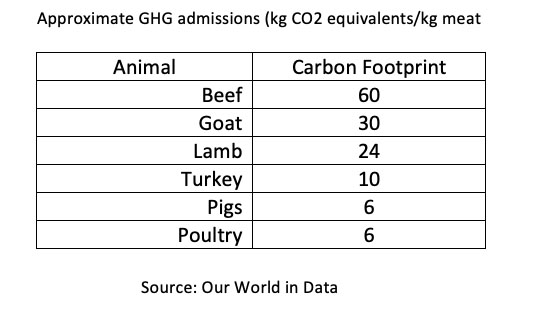

A study in Nature Food suggests that meat production accounts for roughly 60% of GHG generated by food agriculture. Searching for means of reducing food waste in general and for meat products more specifically might be both an economic win, reducing costs and food insecurity, and an environmental win, reducing GHGs. Before looking at the nuts and bolts of the research, the math is fuzzy, based on best estimates, making the relative values more helpful than the absolute numbers.

Absolute Losses in animal lives

- Chickens: 16.8 billion animals were lost or wasted, representing 93.6% of all animal life loss.

- Turkeys: 402.3 million animals were lost or wasted, representing 2.2% of all animal life loss.

- Pigs: 298.8 million animals were lost or wasted, representing 1.7% of all animal life loss.

- Goats: 195.7 million animals were lost or wasted, representing 1.1% of all animal life loss

- Sheep 188 million animals were lost or wasted, representing 1.1% of all animal life loss

- Cattle 74.1 million animals were lost or wasted, representing 0.4% of all animal life loss

You can multiply these lives lost by their body weight and get a sense of which animal source of meat waste is responsible for the most significant amount of GHG. Save yourself the calculation; you know it’s going to be beef.

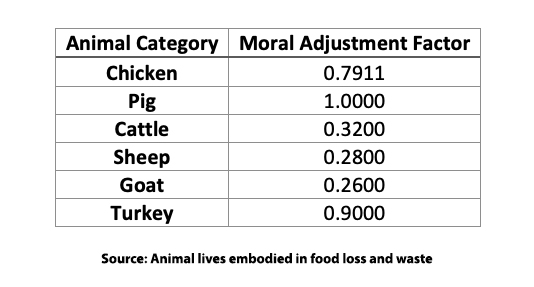

A moral adjustment for animal welfare

There is an oddity about our relationship with animals as food termed the meat paradox. The meat paradox revolves around the conflict between enjoying the taste and nutritional benefits of meat while facing ethical concerns related to animal welfare and the environmental impact of meat production. Those conflicted views are termed cognitive dissonance, the psychological discomfort of holding contradictory beliefs. We experience cognitive dissonance in many areas of our lives.

If the waste of these animals’ lives was insufficient to rouse concern, the researchers introduced a consideration of animal welfare, under the assumption that death for sentient creates was worse than death by the truly clueless. The mathematical rejiggering termed a “moral adjustment” accounted for the different species' ability to suffer and perceive their situation. It starts from a species-centric value of 1 assigned to humans, with animals assigned a proportional moral adjustment factor based on their number of neurons or brain mass. Any observer of the human condition can argue that these metrics may apply in the bias-free world of science but have little to do with the real world where feelings and, dare I say, implicit bias put their thumb on the moral adjustment scale. Few of us are interested in eating Fluffy, our dog, and given the overall love of bacon, pork, the other white meat, will continue to be eaten despite the pig being considered our sentient equal.

If the waste of these animals’ lives was insufficient to rouse concern, the researchers introduced a consideration of animal welfare, under the assumption that death for sentient creates was worse than death by the truly clueless. The mathematical rejiggering termed a “moral adjustment” accounted for the different species' ability to suffer and perceive their situation. It starts from a species-centric value of 1 assigned to humans, with animals assigned a proportional moral adjustment factor based on their number of neurons or brain mass. Any observer of the human condition can argue that these metrics may apply in the bias-free world of science but have little to do with the real world where feelings and, dare I say, implicit bias put their thumb on the moral adjustment scale. Few of us are interested in eating Fluffy, our dog, and given the overall love of bacon, pork, the other white meat, will continue to be eaten despite the pig being considered our sentient equal.

With or without moral adjustment, chickens are the most impacted species, demonstrating the vast number slaughtered and consumed globally. Pigs, considered to have the highest capacity for suffering and the greatest ability to perceive their situation, move up into second place on a list no one wants to be on. Cattle, sheep, and goats with less apparent cognitive abilities fight it out for the remaining places.

More practically, the researchers consider at what point in the food chain the greatest waste occurs.

Losses along the Food Supply Chain (FSC)

The most wasted animal life losses occur at either end of the food supply chain. Agricultural production accounts for 24.9% of life losses and 26.7% at home and restaurant consumption. This latter component is what is typically termed food waste in the media. Losses during storage and handling were the lowest at 7.8%, while losses during the processing, packing, and distribution phases accounted for 40.6%.

The specifics of which animal lives were wasted also varied with the location on the food supply chain, with chickens accounting for most of the lives lost in agricultural production pig lives wasted more during storage and handling. Cattle reflected the most lives wasted in the final consumption phase.

The explanation for these variations resides, in part, in where on the globe the food supply chain resides.

Where do losses occur globally?

- Production-based losses are highest in Latin America, North Africa, Western & Central Asia, and especially Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Losses in South and Southeast Asia are dominated by distribution, processing, and packaging losses.

- Consumption-based losses dominate North America & Oceania, Europe, and Industrialized Asia.

The greater loss of pig lives in the distribution, packaging, and processing phases is related to China's production of the most pork. The loss of cattle lives at consumption is associated with the US consuming the most beef.

There are other ways to further characterize meat loss and waste besides regionally. While industrialized Asia has the most absolute animal life losses, North America and Oceania have the highest per-capita life loss. Economic and cultural circumstances result in Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia consuming the least amount of meat and having the least losses, 4-5%, compared to 34% in the US.

“There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.”

― Thomas Sowell, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles

The study found that reducing meat loss and waste (MLW) could save many animal lives, reflecting both an economic and animal welfare good. But how and where to apply those savings yields unintended consequences. For example,

- Reduction in the waste associated with cattle yields fewer lives lost, sentient or not, than sparing chickens. But those ruminants are responsible for far more GHG emissions than chickens. Do we optimize for lives and animal welfare or environmental concerns? Reducing MLW could also help improve the lives of animals by reducing the number of animals raised and killed for food.

- The data would suggest that reductions in food waste at either end of the food supply chain are the points of greatest capacity for improvement. However, interventions at the consumer level may be more effective in reducing waste, while production-level interventions may be more effective in reducing animal suffering. Ignoring those intermediate steps in the chain may further endanger animal welfare and perhaps impact shelf life. [1] By definition, the food supply chain is linked; the phases are not independent.

- Reducing meat loss and waste could potentially harm food security by reducing the quantity of food available. Or paradoxically, increased overall GHG emissions - lower prices for meat will encourage increased consumption or production shifts to less efficient locations that may have reduced transportation costs.

- The most effective solutions for reducing food loss and waste vary depending on the region. In developed countries, the most effective solutions are to reduce food waste at the consumption stage and, to a lesser degree, improve food distribution and storage. The most effective solutions in developing countries are to improve agricultural practices and reduce post-harvest losses.

To maximize benefits for animals, people, the environment, and the economy, it is crucial to strike the right compromise.

In the US, because of the scale of production, chicken meat is a powerful lever for change. That has much to do with the conditions in our factory farms. The Vox article referenced in the sources details that issue more. But I will leave you with a more entertaining presentation of the same concerns.

Data in the introduction courtesy of the Visual Capitalist

[1] There is a host of conflicting literature on the impact of stress on animals being slaughtered. That said, meat processors do take steps to lessen their stress.

Source: Animal lives embodied in food loss and waste Sustainable Production and Consumption DOI: 10.1016/j.spc.2023.11.004

We raise 18 billion animals a year to die — and then we don’t even eat them. Vox