Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, enacted in 1996, provided the shielding mechanism with which SM hosts cloak themselves. This provision enabled what many claim is an insidious invasion of the minds of millions of Americans while simultaneously insulating SM platforms from liability under the color of protection enjoyed by book publishers:

"No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider."

Today, Meta and its social media affiliates (the Meta “Mafia”) generate large revenues from advertising tied to algorithms optimized to obtain and maintain attention. Cyberbullying, body shaming, disinformation waged against public policy, and hate-based rhetoric were protected by the First Amendment and Section 230. Unlike Child Porn, free speech protected the content of the posts.

When children sickened or died “by virtue” of SM consumption, parents sued -- with mixed success. First Amendment lawyers and their champions (successfully) claimed with wide-eyed and smug complacency that the antidote to “bad speech” -- is more speech, not no speech. But for a poison delivered 24/7, staffed by bots, foreign operatives, and now supercharged with artificial intelligence – there is no such thing as more speech, more room, more space, or more time. More speech only enables posts to go viral. In the last weeks, a successful offensive to reduce these harms finally seems underway.

The lawsuit

In recent months, 42 Attorneys-General have banded together, filing a lawsuit directed at the “Meta Mafia” to curtail their activities and hold them accountable for their allegedly nefarious ways. In mid-November, Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rodriguez of a California Federal Court issued her decision addressing the defendant’s motion to strike the complaint, which raised their hitherto almost inviolate weapon of mass protection: Section 230 of the Conspiracy Act.

The lawsuit details the defendants’ modus operandi activities, claiming, in essence, that the defendants perversely targeted children and knowingly designed their products for the purpose of addicting them, and by extending the time the user interfaced with the platform, “Meta can collect more data on the user and serve the user more advertisements.” The results are horrific.

From the Complaint:

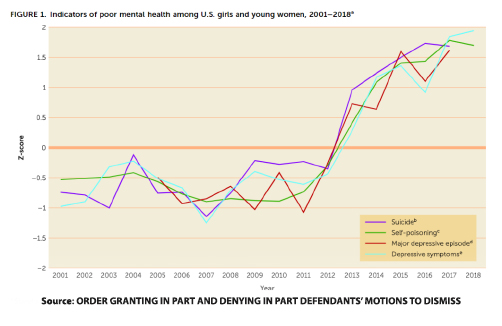

“Beginning with Instagram’s rise in popularity in 2012…the rates of suicides, self-poisonings, major depressive episodes, and depressive symptoms among girls and young women jumped demonstrably.”

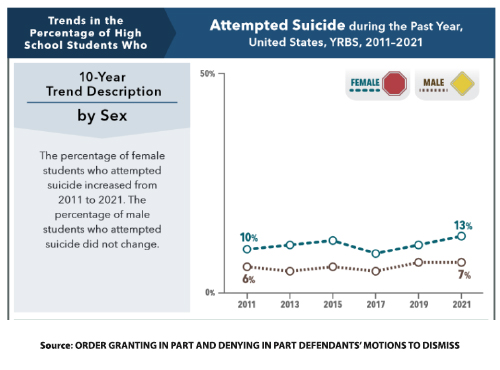

“Particularly concerning is the rise of suicidal ideation among girls …. According to the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, in 2011, 19% of high school girls seriously considered attempting suicide. By 2021, that figure reached 30%.”

As the judge summarized the claims:

“Because children still developing impulse control are uniquely susceptible to harms arising out of compulsive use of social media platforms, defendants have “created a youth mental health crisis” through the defective design of their platforms…. [Further], these platforms facilitate and contribute to the sexual exploitation and sextortion of children as well as the ongoing production and spread of child sex abuse materials (“CSAM”) online.”

The challenge faced by the plaintiffs was to eschew claims involving the content of the posts, as this is protected by Section 230 (plus the First Amendment). Instead, the complaint casts social media as a product – subject to product liability laws, alleging the defendants knowingly harmed their users through wrongful product design and negligent practices, failed to warn of known dangers and violated existing laws such as the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) which prohibit “unlawful collection of personal data of users [some under the age of 14] without parental’ permission…. [and] which allegedly constitute unfair and/or deceptive acts or practices.”

“Meta has exploited young users of its Social Media Platforms, including bycreating a business model focused on maximizing young users’ time on its Platforms; (2) employing harmful and psychologically manipulative Platform features while misleading the public about the safety of those features; (3) publishing misleading reports purporting to show low rates of user harms; and (4) in spite of the overwhelming evidence linking its Social Media Platforms to young user harms, refusing to address those harms while continuing to conceal and downplay its Platforms’ adverse effects.” - Plaintiff’s Complaint

The plaintiffs crafted a litany of claims raising design defects of platform architecture and algorithms that do not revolve around content, but rather cause addictive behaviors and harmful effects. These allegations claim to result from a product designed to capture and imprison the user’s attention for prolonged periods – to “fatten the pockets” of the defendants by fostering advertising sales. These include:

- Lack of Screen Time Limitations (blurring the concept of passing time and duration of use).

- Intermittent Variable Rewards designed to maximize dopamine reaction.

- Rewarding use with “elevated status,” “trophies,” and posting social metrics, such as “likes.

- Ephemeral (disappearing) content creating a sense of urgency, fostering “coercive, predatory behavior toward children.”

- Notifications by phone, text, and email to draw users back.

- Algorithmic Prioritization of Content by tracking user behaviors … to hold [users’] attention.

- Filters - so users can edit photos and videos before posting, enabling the proliferation of “idealized” content reflecting “fake appearances and experiences,” resulting in, among other things, “harmful body image comparisons.

- Lack of age verification and parental controls.

Both sides beseeched the Court to take an all-or-nothing/win-lose approach. The Court refused, issuing a highly nuanced and particularized decision - granting some and dismissing other claims. For now, the case continues and discovery will proceed. This will likely uncover the extent to which Meta knew of the deleterious effects of its product. That they did know has been established via whistleblowers (now former employees) [1]

The Court’s Ruling:

The Court found social media to be a product subject to product liability laws based on its functional equivalence to other products, and ruled that these platforms had a duty to act reasonably and warn of known dangers, determined that failure to provide for parental consent and age verification was a valid claim, and that the filter devices which altered appearances in an undisclosed fashion and encouraged posting of dangerous behaviors, were actionable. The Court did throw some bones to the defendants, notably ruling that the mechanism connecting adults and children (which plaintiffs claim fosters sexual harm to children) is protected by Section 230 and, again, unlike Child Porn, that the First Amendment protected the reward mechanisms facilitating this behavior.

I will take a deeper dive into the decision, including my objections, in the next post

[1] Francis Haugen, is a former product manager and data engineer at Facebook, Arturo Bejar, a former Facebook engineer director.