Before jumping to the claim of a first amendment privilege, a new study in JAMA Network Open illuminates how extensive a problem physician information during COVID might have been. The researchers used CDC guidelines as their baseline “truth” and sought social and mainstream media articles and posts by physician authors. [1] The tweets in what was Twitter and Is now X was somewhat biased towards America’s Frontline Doctors because of their high volume and large following.

Researchers identified 50 licensed physicians, 88% with active licenses, across 28 specialties and 29 States. Categories of misinformation include the safety and efficacy of vaccines, the effectiveness of masks and social distancing in reducing the risk of contracting COVID, the use of medications to prevent or treat COVID that had not completed clinical trials or had not been FDA-approved for that indication, and various conspiracy theories.

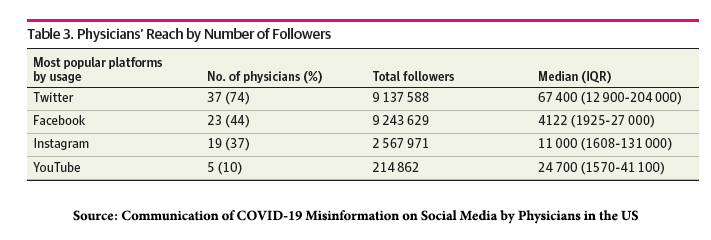

Vaccine misinformation was the most widely posted, 80%, followed by conspiracy theories, 54%, and medication misinformation, 52%. Postings were most frequently across multiple platforms, but the most common was Twitter, 71%.

Even if we were to treat the followers as separate individuals, the reach of these physician misinformers was roughly 8% of adults in the US.

Vaccines were decried as ineffective using cases of COVID among the vaccinated compared to those among those not vaccinated, not accounting for the very different sizes of the populations being considered. A misinforming or misleading technique often cites relative rather than absolute risks – relative risks are always higher, and large numbers attract attention. Vaccines were also characterized as harmful to many individuals citing unexplained deaths from those vaccinated even months after vaccination – an example of the correlation versus causation fallacy. The issue of myocarditis, elevated in the J&J vaccine, was conflated by not considering the simultaneous benefit.

Ineffective medications were touted using anecdotal evidence or “studies” that were deeply flawed or fabricated. Masks were derided for increasing cases despite their use but with no evidence of how cases would increase in their absence. Additionally, masks were considered harmful, restricting oxygen and causing retention of CO2, a topic I have personally debunked. Finally, a range of conspiracy theories spoke more to our distrust of institutions and individuals than to any actual plot.

“National physicians’ organizations, such as the American Medical Association, have called for disciplinary action for physicians propagating COVID-19 misinformation, but stopping physicians from propagating COVID-19 misinformation outside of the patient encounter may be challenging.”

Dr. Nass and Maine’s Board of Licensure in Medicine (BOLIM)

Meryl J. Nass, MD, a family practitioner in Maine, had her medical license suspended by Maine’s BOLIM for two reasons: her clinical care involving three patients and her use of social media to convey information “violating a rule adopted by the Board.” The rule

“licensees may face disciplinary action should they “generate and spread COVID-19 vaccine misinformation or disinformation.”

Her social media statements were much the same as reported in the JAMA study, raising concerns about vaccine efficacy, promoting the use of ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, and conspiracy-type statements such as this one.

“Operation Warp Speed is the result of an agenda that “seems to be the same one that has been in play since 2001, you know, the 9/11. Which is increased surveillance, right, increased central control, and some blurring of national borders and national sovereignty.”

Dr. Nass is suing the BOLIM for violating her free speech rights. Does the First Amendment cover her speech, or does her role as a physician limit what she can say? This is a cross-aisle issue, just as important to advocates of abortion as it is to those like Dr. Nass, advocating for very off-label therapies.

A citation in the JAMA article, a discussion of Professional Speech by Professor Claudia Haupt, a Visiting Professor of Law at Yale Law School specializing in the intersection of the first amendment and public health, can help us better understand the legal issues revolving around physicians' speech.

The state may regulate the professions, but “[b]eing a member of a regulated profession does not . . . result in a surrender of First Amendment rights.”

Professor Haupt puts forward a legal theory, their equivalent to a hypothesis, that seeks to define professional speech. The law recognizes several forms of speech. Commercial speech, found in advertising, can play a bit more “fast and loose” with the truth. It is built upon an information asymmetry; the advertiser knows more than the customer, but that asymmetry is not as significant as between a physician and patient. In commercial speech, the speaker pays, not the listener. Again, in the discourse between physician and patient, that payment role is reversed; the listener pays.

Then there is personal speech, not the “‘speech . . . uttered in the course of professional practice,’ [but the] ‘speech . . . uttered by a professional.’” This is the speech of Dr. Nass on social media and in interviews.

“When the professional’s advice is distributed generally or to the public at large, outside of the professional-client relationship, it is most likely not professional speech.

When professionals speak in such a manner, they act as ordinary citizens participating in public discourse and accordingly enjoy ordinary First Amendment protection.”

It is, indeed, protected by the First Amendment and was dropped as a reason for the suspension of Dr. Nass’s medical license. When I speak as a citizen, even when including my credentials to lend a halo of authority, I may speak as I wish, even contrary to accepted medical beliefs.

Professional speech, in Professor Haupt’s view, is a third variation. It is

- To provide professional advice – There is a significant asymmetry to the knowledge; the physician may not know best, but they certainly know more. In addition, since the communication of information to reduce this disparity may significantly impact the listener’s (patient’s) health, physicians have a fiduciary responsibility to speak and act in the patient's best interest, not themselves.

- Convey a knowledge community’s insights – Among the fiduciary responsibilities are to faithfully convey the medical communities “best” practices and knowledge. When that information is not appropriately communicated, it can provide a reason for malpractice litigation; the physician failed to meet the “standard of care.”

- It occurs within the professional-client relationship – An established physician-patient relationship must exist.

The BOLIM suspended Dr. Nass’s licensure because she had violated the care of her patients, not in the context of her advice, but in her failure of documentation and falsification of records and information. The patient’s harmed by her recommendation respecting their individual treatment have recourse to malpractice litigation. In my view, the BOLIM had cause for their actions that had little to do with free speech and much to do with providing care. [2]

There is another form of speech, government speech. Professor Haupt cites examples of statements and actions required by the government to present pro-life views for those women seeking abortions. That is not significantly different than the Florida law banning questions about gun storage by pediatricians, which was overturned as a violation of the First Amendment. Nor may it be different from the messaging of the BOLIM on what a physician might say about COVID vaccines. In this setting, when

“…the state demands that physicians communicate certain claims to their patients in materials of the physicians’ own design, the state effectively tries to obscure authorship even though it is the state that retains effective control over the message communicated.”

In this instance, the government is dictating professional speech, which should not be allowed. Dr. Nass’s suit may well hinge on this attempt at limiting physician’s professional speech, but since it was not part of the final BOLIM’s decision to withdraw her license, that may prove a tough case.

[1] All authors included their MD or DO certification in their bylines

[2] I feel the same about the case of Dr. Ruan and his criminal conviction involving dispensing pain medications.

Source: Communication of COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media by Physicians

in the US JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.28928

Doc Suspended for COVID Misinfo Sues, Cites Freedom of Speech MedPage Today

Professional Speech Yale Law Review