Assembly theory offers a way to attempt to identify chemicals created biologically rather than through chance, through the process of their creation rather than the underlying physical laws.

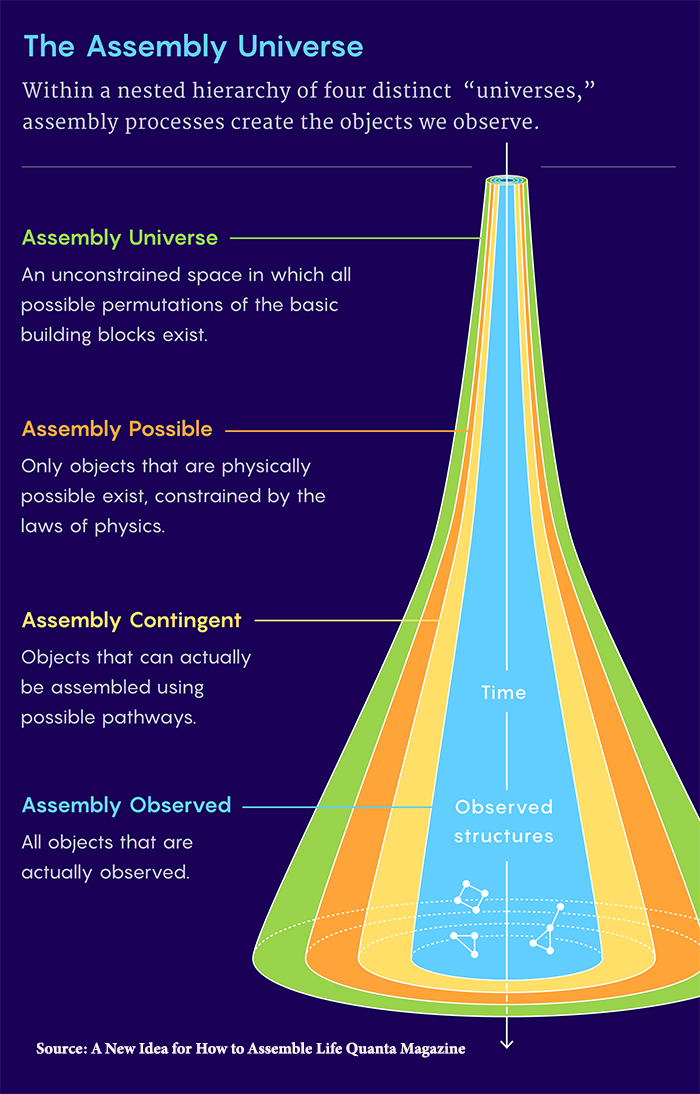

As the graphic to the left depicts, there are four levels to a universe of chemicals. The largest, the assembly universe, is all the possible ways chemical elements combine. That is greatly reduced by the “laws” of physics to those that can actually be created, although how they are made and at what energetic cost is unknown.

At this point, the “rubber hits the road,” and the objects are further constrained by “possible pathways” of production. Possible implies a degree of uncertainty; after all, we do not know all the means of biological transformations. And if a chemical structure has biological value, then one would expect to find many copies – we do not have just a few hemoglobin molecules; we have roughly 260 million in each of us.

At this point, the “rubber hits the road,” and the objects are further constrained by “possible pathways” of production. Possible implies a degree of uncertainty; after all, we do not know all the means of biological transformations. And if a chemical structure has biological value, then one would expect to find many copies – we do not have just a few hemoglobin molecules; we have roughly 260 million in each of us.

Assembly theory begins with building blocks and defines a pathway for those blocks to form more complex chemicals. The number of steps defines a complex molecules assembly index (AI).

“Their results showed that, for relatively small molecules, the assembly index is roughly proportional to molecular weight. But for larger molecules (anything bigger than small peptides, say), this relationship breaks down.”

We can reliably estimate AI for a compound using mass spectrography, as the Rover does on Mars. Using an extensive database of chemicals, researchers have identified a “cut-off” range of assembly indices that can separate chemicals that are a product of biological interactions. Of course, while statistically useful, this cut-off is somewhat arbitrary; yeast and beer were considered biological objects, but Scotch whiskey, not so much. [1]

There is much more to say and learn on the topic. I strongly urge you to follow the links to the source material originally posted on Quanta and then reprinted by Wired. It is worth the read.

[1] Conflict of interest disclosure: while I enjoy a good single malt scotch, I am more drawn to bourbon in these later years.