Much of our data comes from the CDC, which collects state-wide data from “Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs), which are representatives of diverse clinical and non-clinical backgrounds who review the circumstances around pregnancy-related deaths to identify recommendations to prevent future deaths.”

Pregnancy-related deaths are temporally related, defined as occurring during or within a year of the end of pregnancy, and causally related to pregnancy or its management. Maternal deaths involve a short time range occurring during pregnancy or the first 42 days (6 weeks) after the end of the pregnancy.

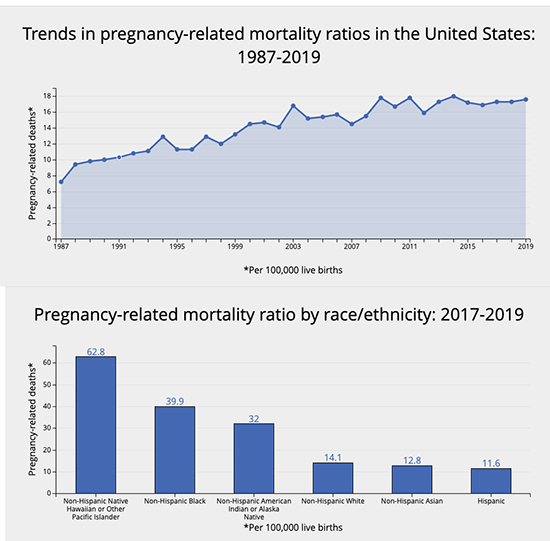

As the data clearly show, we are not making significant inroads into lowering our pregnancy-related mortality, which continues to rise. And despite the media headlines noting the disparity in those deaths among Blacks, whose rate is 3-fold those of Whites, it is 2-fold greater than indigenous Americans and 6-fold greater than Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

As the data clearly show, we are not making significant inroads into lowering our pregnancy-related mortality, which continues to rise. And despite the media headlines noting the disparity in those deaths among Blacks, whose rate is 3-fold those of Whites, it is 2-fold greater than indigenous Americans and 6-fold greater than Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

Maternal mortality for Asians and Hispanics is slightly less than for White mothers.

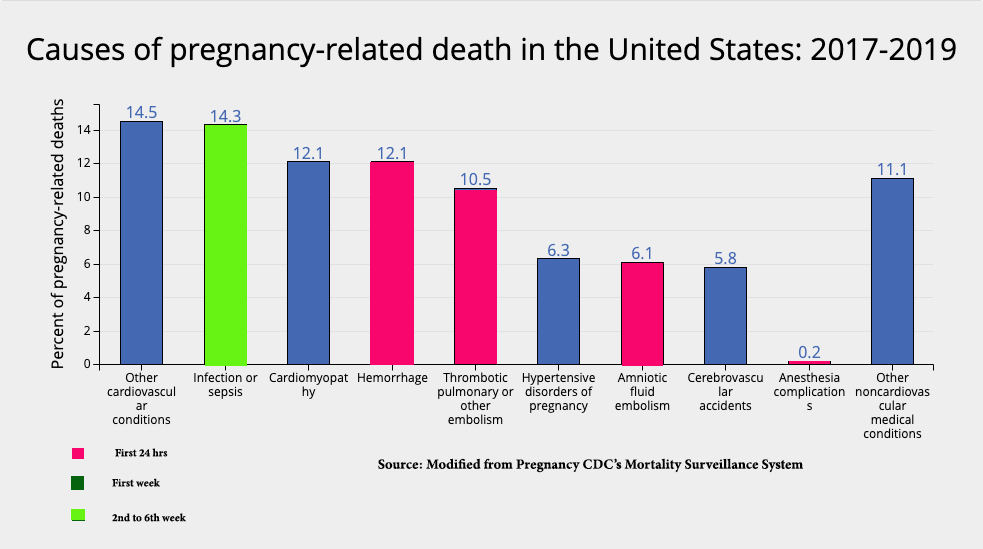

Roughly a quarter of pregnancy-related deaths occur during pregnancy and another quarter on the day of delivery or within the first week. 53% occurred in the time frame of one week to six weeks after surgery. The graph shows the specific type of complications and their usual time frame.

But the graphic fails to identify another salient feature. More specifically, “mental health conditions (including deaths to suicide and overdose/poisoning related to substance use disorder)” are responsible for 23% of maternal deaths. It also fails to show the leading cause of death stratified by race. Mental health issues were the leading cause of fatalities among Whites and Hispanics; for Blacks, it was cardiac and coronary conditions, including pre-eclampsia [1]; hemorrhage was the leading cause of death for Asians.

“More than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths were preventable.”

This statement frequently often follows the sentence of the increased risk of maternal mortality in Black women. But it is difficult to find the underlying data because preventable is an ambiguous term.

“A death is considered preventable if the committee determines that there was at least some chance of the death being averted by one or more reasonable changes to patient, community, provider, facility, and/or systems factors.” [emphasis added]

As a physician, all deaths are, to one degree or another, hopefully preventable. But the 80% reveals another difficulty in healthcare, termed the “last mile” problem – the opposite of the advantage of low-hanging fruit.

While hemorrhage accounts for 12% of our maternal deaths, it is responsible for 94% of global maternal deaths. The reason,

“…the full range of resources to control hemorrhage is not available, [including] the usual obstetric measures, blood availability, hemostatic medication, and hematologic expertise….”

Blood availability and hemostatic medications are far more readily available here. The last mile problem for us is identifying the need for and obtaining hematologic expertise – which is not as easily solved as creating and maintaining a blood bank. And that high degree of hemorrhage hides another problem, the underlying degree of mental health issues that surely are present in middle and low-income countries as well as the US – hemorrhage is far more likely to be the proximate cause than mental health in countries without a blood bank.

“…there were no significant differences in preventability by race/ethnicity.” - CDC MMWR

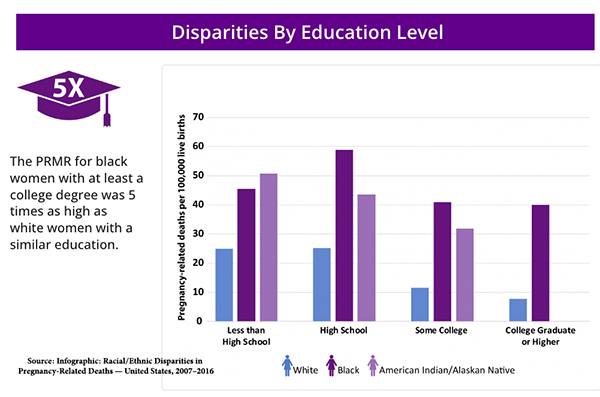

Differences in outcomes were attributable to differences in access and quality of care and the prevalence of chronic illness. More specifically, hypertension, the prelude to cardiovascular complications and pre-eclampsia, is “more prevalent and less well controlled in black women.” We are failing to identify high-risk mothers. [2]

The quality of care is also felt to be a significant factor, attributable to lower “quality” hospital care or implicit bias. It is hard to argue those points when you consider this graphic from the CDC demonstrating the pregnancy-related mortality ratio, PRMR (maternal mortality):

There is no one size fits all approach

The differences in the underlying causes of maternal mortality vary with race, ethnicity, and geography. Metropolitan maternal deaths hover in the 15/100,000 live births, but these numbers rise to 21-26/100,000 (a 73% increase) as we move further into rural areas. There is no easy solution to a lack of medical personnel and facilities in rural areas.

With 53% occurring after that time frame, we must consider prolonged follow-up care – a “fourth trimester.” A six-week check-up postpartum may be difficult for the new mother, balancing many more activities and responsibilities. And the time frame of one visit at six weeks, when nearly half of that 53% of maternal mortality occurs, may be inadequate to pick up early warning signs and symptoms.

These are the hurdles of the “last mile" -- problems that are not intractable but are not easily solved by desire or money. These problems require the humans of healthcare, be they nurses, midwives, physician “extenders,” or physicians. Telehealth can project their “presence” into the homes of mothers unable to get to the office because of transportation problems, long distances, and the day-to-day care needed for a newborn.

[1] Pre-eclampsia is a complication characterized by high blood pressure and damage to the liver and kidneys and is responsible for about 7% of maternal deaths. It typically occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy and requires medical attention, as it can adversely affect both the mother and the baby. It can be treated with medications but often requires delivery to resolve the condition. This May, the FDA approved a blood test to identify women at risk for pre-eclampsia, which should heighten surveillance and subsequent treatment. And researchers have developed an algorithm to more quickly identify at-risk mothers based on blood pressure during serial prenatal visits.

[2] “In the United States during 2019-2021 (average), White (82.9%) mothers had the highest rates of early prenatal care, followed by Asian/Pacific Islanders (81.3%), Hispanics (72.3%), blacks (68.6%) and American Indian/Alaska Natives (64.9%).” Prenatal Care

Sources: CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System

Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer The Commonwealth Fund

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016 CDC MMWR