ADHD is a syndrome, a constellation of symptoms grouped to define a spectrum of disorders involving attention to “detail, organization skills, memory, and self-control.” There is no specific finding, objective or subjective, what physicians would call a pathognomonic marker, that says this person has ADHD, and this is its severity.

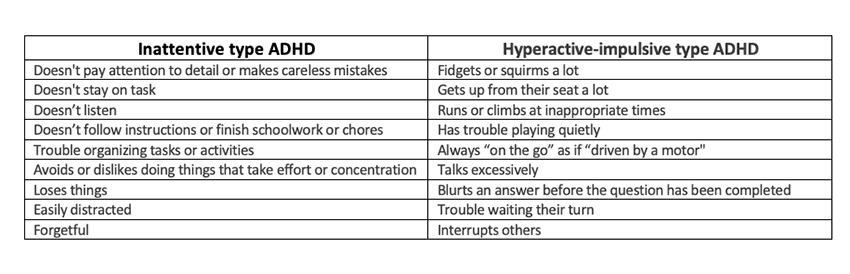

The diagnosis of ADHD is made by considering a checklist of symptoms, guidelines developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The group has identified three types of the disorder:

One needs six symptoms in either column and “a few in the other” to make a clinical diagnosis. [1] The symptoms must have persisted for at least six months, beginning before age 12. The symptoms must have been present in two or more social settings, i.e., home and school, and significantly affected the child.

One needs six symptoms in either column and “a few in the other” to make a clinical diagnosis. [1] The symptoms must have persisted for at least six months, beginning before age 12. The symptoms must have been present in two or more social settings, i.e., home and school, and significantly affected the child.

The requirement of an “impairment” is a two-edged sword. It certainly is meant to raise the bar on when behavior becomes a liability, but it is a subjective judgment prone to cultural bias. In addition, since behavior is judged in the context of varying social circumstances, it is quite possible for an individual to “outgrow” and “redevelop” the impairment as their life changes. Up to 50% of patients carry these symptoms into adulthood.

In a chart review of “1594 patients across 188 pediatricians at 50 different practices,” only 70% of children diagnosed with ADHD had documentation meeting the APA criteria. Fewer than half of the patients started on medication had a follow-up in the next month to assess whether that therapy was effective. Only 13% of patients were started on cognitive behavioral therapy, which makes sense to the degree that getting patients to focus is the prime difficulty. The overwhelming majority, 93.4%, were started on medications. And that brings us to Adderall.

Adderall and company

The medications used in treating ADHD are amphetamines. Adderall is the brand name of one of the most popular options, but there are others, all in short supply. These medications promote a paradoxical effect of giving individuals who have ADHD more focus. The greater focus for these individuals in the school setting enhances their performance.

When used for non-medical purposes, amphetamines are highly addictive in that they create a craving that requires, in many instances, escalating doses. But like opioids in treating chronic pain, using these drugs in the setting of the chronic illness of ADHD doesn’t require escalating doses; most patients have achieved stable levels, and there is no harmful drug-seeking behavior. The definition of addiction blurs for ADHD and chronic pain patients.

The increased focus experienced by patients with ADHD taking an amphetamine is mistakenly seen as a general "performance enhancer" for everyone, making it an attractive helper to students rushing towards deadlines. Most evidence shows no cognitive improvement; you just stay up later to cram or finish a paper. That said, there is a significant problem with diverting Adderall and similar medications to treat poor study habits rather than an underlying medical problem. [2]

The combination of being highly addictive and likely to be diverted makes these Schedule II drugs just like opioids. The use of amphetamine salts in treating ADHD shares another quality with opioids used in treating chronic pain – there is very little evidence of problems, including addiction, when physicians use these medications in close, long-term patient care settings.

Demand

“All of our drug shortage infrastructure, and everything we have in place in this country to mitigate the impact of shortages is based on potential disruptions in supply. It’s been very unusual to have a shortage based on increase in demand.”

- Michael Ganio, Sr. director of pharmacy practice and quality, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP)

The demand for Adderall and these other stimulants has increased dramatically over the past few years. Based on all-payer claims, Trilliant generated this chart.

The increasing demand for these medications has been explained, especially by patient advocates, as a rising awareness among parents and teachers of this diagnosis. But the pandemic wrought other changes; more people were working at home, and more children were learning remotely.

Prescriptions have decreased slightly among adolescents, perhaps due to an increase in remote learning and an inability of teachers and counselors to evaluate individuals in this setting.

Prescriptions have decreased slightly among adolescents, perhaps due to an increase in remote learning and an inability of teachers and counselors to evaluate individuals in this setting.- There has been little change for middle-aged adults, presumably because those with ADHD have already been identified.

- “In hindsight, it is clear that the emergence of digital mental health platforms enabled significant increases in prescribing, particularly for the Millennial generation.” Forty percent of all 2022 prescriptions were from “telehealth visits,” compared to 2% before the pandemic. What is disturbing, as Trilliant points out, “Notably, there are more adults receiving prescription Adderall than there are with a formal ADHD diagnosis. This discrepancy likely speaks to the number of individuals using a direct-to-consumer, self-pay service in this clinical scenario.”

"There's a lot of concern among my colleagues that a new paradigm, a new way of doing evaluations and treatments, may not be grounded in the established sort of methods that people have basically developed over years of practice."

- Craig Surman MD, Associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School

According to the Advisory Board, a health consultancy, the significant increase in prescriptions from online pharmacies raises concerns about whether there is a firm underlying medical diagnosis or that individuals may be “gaming” the system to divert these “performance enhancers.” Based on concerns of nurse practitioners working for Done and Cerebral, two telehealth companies, Walmart, CVS Health, and Walgreens, have all “reported delaying or blocking prescriptions of Adderall from clinicians at Done and Cerebral.” Truepill, the pharmacy partner of Cerebral, has halted filling these prescriptions “out of an abundance of caution.”

Supply

Welcome to the supply chain comprising manufacturers, distributors, and retail pharmacies, brick and mortar or online. “Helping” the “invisible hand” of these markets are the regulators, in this case, the DEA and FDA.

The largest manufacturer of Adderall and its generic equivalent is Teva, which in August had temporary supply problems “associated with packaging capacity constraints.” While those issues have been resolved, there remains a shortage even though, as reported by Bloomberg:

“companies had at least 34,980 kilograms (77,000 pounds) of Adderall’s raw ingredient – amphetamine – on hand at the end of last year, suggesting there was plenty to go around.”

And the reason for this, the DEA sets capacity limits on how much of these Schedule II drugs are manufactured, basing their production limits on the previous prescriptions. We can question whether a law-enforcement agency should set production limits, but at the very least, we can all agree that those limits must be updated more than annually. Frequently updating capacity caps allows sufficient “slack” in a supply chain to overcome the weekly and monthly variations in demand.

“Demand forecasts based on historical data couldn’t predict the sharp rise in ADHD diagnoses during the pandemic.”

- Michael Ganio, Sr. director of pharmacy practice and quality, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP)

The limits set by the DEA are partially based on FDA estimates of need - again based on historical prescribing. The DEA then divvies that total between manufacturers, releasing it as they see fit. Neither the DEA nor manufacturers will indicate the percentage of product they are allowed to manufacture, so it is “difficult to know to what extent shortages of this common medication rests with the government or the companies it oversees” – so much for government transparency in drug supply.

Whatever supplies there are, then move to the distributors. Ninety percent of pharmaceutical distribution is managed by three companies: Cardinal Health, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen. If the names are familiar, that is because these are among the “bad actors” in the opioid crisis. They form a sort of monopoly, an oligopoly, which involves a small number of companies rather than just one. They have great control over the downstream flow of medical products, not just pharmaceuticals. They exert their power by making “sweetheart” deals with health systems, hospitals, and retail pharmacies to provide a discount on some products in exchange for a guarantee of purchase of other products.

During the opioid crisis, these three distributors failed to act upon red flags placed in their computer systems to identify large purchases of opioids. As a result, they have had to pay fines and “reparations” to the federal government and States. They have taken a much different approach to Adderall and its friends. Their computers are set to identify anomalies in purchasing, dramatic increases in pharmacy prescriptions, or an imbalance of prescriptions, more for the Adderalls, not so much for other medications suggesting an ADHD “surge.” Once an anomaly is identified, it is incumbent upon them to verify a pharmacy's actual requirement.

In earlier times, that would have meant a phone call from the local distributor to the pharmacist and a quick chat about incoming prescriptions. But when three companies control 90% of the market, they are too big to know any but the largest of your purchasers, health systems. They are too big to have someone take the time to do the due diligence and speak to the pharmacies to see whether this is an increase in legitimate prescriptions or a diversion. Instead, and I am sure on the advice of in-house counsel, you simply cut the pharmacy off from further medication. After all, while it may hurt the neighborhood pharmacy, they are a rounding error in a company's revenue, and where else do they have to go?

Matt Stoller writes on the effects of oligopoly regarding the distributors in this way. The enforcement of the opioid settlements assumed that these distributors “are good at what they do, and just sought extra profits by selling more pills.” They were not simply ignoring their obligations; they were “too big to know its customers, or even its employees, and allowed lawlessness and random bureaucratic rule-making to rein.” Their performance now differs only in that they arbitrarily shut distribution down.

Of course, interrupting distribution does not eliminate legitimate demand. In an ideal world, a shortage of Adderall might be addressed by the pharmacy by supplying an equivalent medicine. But the FDA regulations mandate specific equivalents, and when these are unavailable, the pharmacist must secure a new prescription. While this may hinder diversion, it also creates a hurdle in filling legitimate prescriptions. Patients will try other pharmacies, which in turn face the question of whether this prescription will raise a red flag. Here are the voices of addiction specialists writing in Health Affairs:

“Those without a safe supply start looking for medications in other, nonregulated spaces, often finding themselves at risk of violence or conflict with law enforcement. … Prescribed stimulants are commonly diverted for non-prescription use, and thus supply chain shortages likely increase the demand on the “black market,” possibly increasing diversion and worsening shortages as the price of non-prescribed stimulants increases.”

Prohibition has not worked for controlling the use of alcohol, tobacco, or opioids; why would we think it would work for stimulants like Adderall?

What to do

As The New York Times writes about the DEA:

“The agency’s attempt to curtail opioid prescribing did not prevent the tremendous increase in opioid use. … did not respond quickly to the rise of street fentanyl and the worsening of overdose rates that it caused, nor has it been able to significantly decrease availability.

… The DEA has had five decades to prove that it can do better than the FDA in controlling potentially dangerous drugs used in medicine. It has failed.”

If we are to continue to try to control this problem using manufacturing caps, get the DEA out of the process, and update the caps far more frequently. My MBA training says they should be updated in the time frame it takes to place an order with a manufacturer and get it delivered to a distributor.

Require the distributors to do their due diligence in the face of red flags. Promptly speak to the pharmacies and determine whether their algorithms have detected a problem or just a changing pattern of care.

“The minute we ran out of it [Adderall], he was back to, you know, getting in trouble every day, getting up out of his seat. The teachers immediately noticed.”

- Kristina Yiaras, mother of an 8-year-old with ADHD

Act now, for patients with ADHD, the inability to get their medications results in lagging learning in school and losing their jobs. It drives individuals to the black market, and as we have seen with the opioid crisis, that will result in the loss of life because you never know whether fentanyl is in the mix.

[1] A third, “Combined type,” is the most common presentation with symptoms from both columns.

[2] In a meta-analysis of 113,104 subjects, diversion rates for ADHD medications ranged “from 5% to 9% in grade school- and high school-age children and 5% to 35% in college-age individuals. Lifetime rates of diversion ranged from 16% to 29% of students with stimulant prescriptions asked to give, sell, or trade their medications.” Some online pharmacies abet this diversion. Using standard search engines, i.e., Google, researchers identified 62 online pharmacies selling Adderall in 2020. None require prescriptions, pharmacist services, or quantity limits, but all offer various price discounts. Of the 62, 61 were considered rogue or unclassified pharmacies.

Sources:

Adderall shortage comes after surge in telehealth prescriptions Washington Post

The Myth of ADHD Overdiagnosis Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD)

Variability in ADHD care in community-based pediatrics Pediatrics

The ADHD medication shortage is getting worse. What went wrong? NBC News

Understanding Why Adderall Shortages Are Shrouded In Mystery Bloomberg

The Monopolies Behind Adderall Big

Short on Adderall? Blame DEA Production Caps Reason Magazine

Increasing Stimulant Prescriptions To Prevent Overdose Deaths In An Adderall Shortage Health Affairs

People Can’t Get Their ADHD. Medicine, and That’s a Sign of a Larger Problem NY Times

Op-ed: DEA and FDA rules exacerbate Adderall shortage CNBC