OK, that title is a bit overblown, but it's also correct. Sort of. Although incredibly rare, decades ago a small number of people had their fingers chopped off because they were wearing wedding rings.

And it's not because men were caught in flagrante delicto by their knife-wielding wives (1). It was because of radioactive gold that made up their wedding rings; this caused cancers of varying severity, including cases where the fingers had to be amputated. Talk about a metaphor for marriage, right? I'll leave the symbolism to the philosophers in the crowd and stick to the science.

But even the science is a bit shaky.

Radioactive gold? Real, but rare

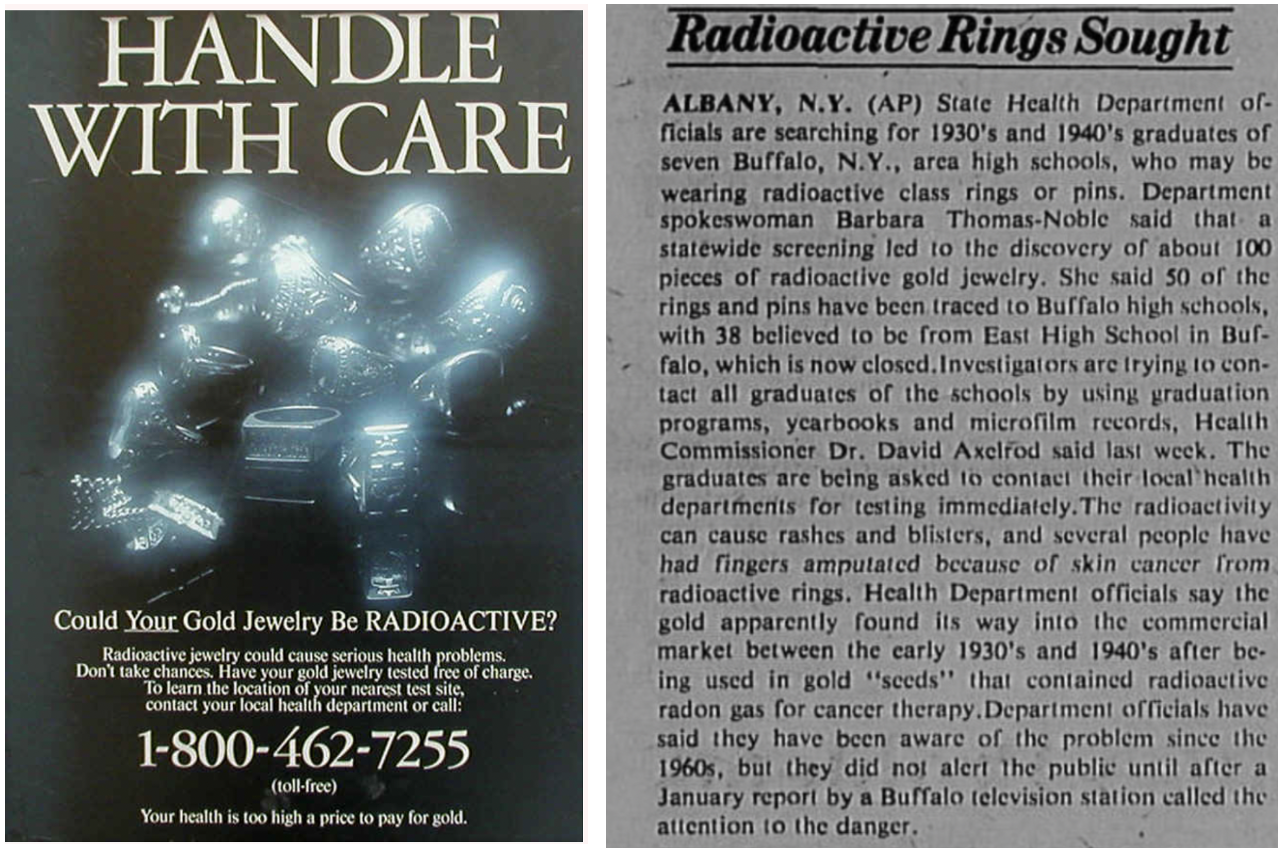

Of all the things in life to worry about, getting cancer from a radioactive gold wedding ring won't make the list, even that of neurotic (redundancy alert) New Yorkers. But in 1981, a cluster of 177 pieces of radioactive jewelry was found in upstate New York and it was responsible for really rare cases of cancer. The jewelry was mostly made in the 1930s and 40s.

Several months ago, health officials said they had discovered a number of contaminated pieces of gold jewelry, which may have caused skin irritations to their owners. Since the start of the year, health officials have spotted about 150 pieces of radioactive jewelry, nearly half of which were class rings or pins from the Buffalo area, dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. Some of the wearers of radioactive jewelry eventually had fingers amputated because of cancer

— Syracuse Herald-American, August 30, 1981

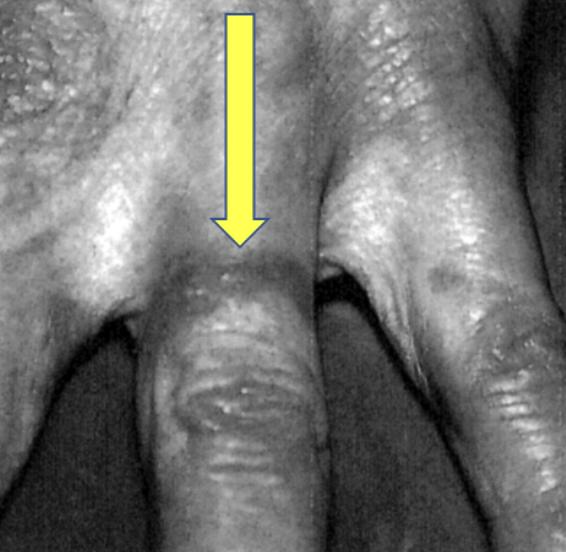

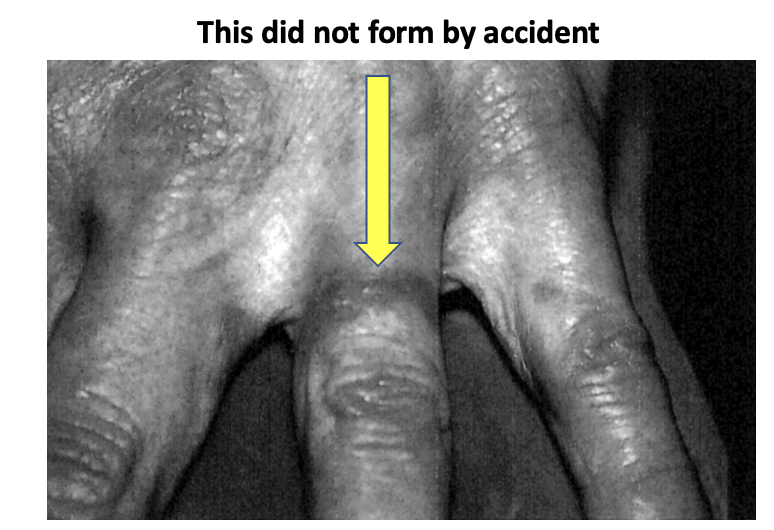

The effect of radioactive wedding rings on ring fingers was first documented in a 1967 JAMA paper by Simon and Harley. The authors reported that a husband and wife developed radiodermatitis on their ring fingers beginning shortly after their marriage 26 years earlier. And a 1968 JAMA letter reported a case of squamous cell carcinoma, which required amputation of the ring finger. There was even a wrongful death suit in 1983, which was thrown out.

Radiodermatitis from a wedding ring. Image: Miller and Aldrich, J Am Acad Derm, 1990;23:360-2.

Why was the gold radioactive?

There are a number of explanations for what happened. Some may even be correct.

- Radon was the culprit

Miller and Aldrich, writing in J Am Acad Derm (1990), concluded that the cancers were attributable to the radon gas that was used to fill hollow gold seeds that were used at that time for brachytherapy to treat prostate and other internal cancers. But, the seeds were later (and illegally) melted down and sold as normal gold. The radon, which came along for the ride, caused the radioactivity disease.

- Gold-198, a radioactive isotope, was the culprit

A 2010 article on the Gold Refining Forum website (just in case you missed it) disputes the first conclusion, claiming it is unlikely that radon gas would still be around after melting the gold seeds (the melting point of gold is 1,948oF). It is hard to argue with this. Instead, the site claims the real culprit was an unstable gold isotope 198Au, which could be formed from the nuclear reaction of stable 197Au with radon.

3. I don't love either explanation. The problem with #1 was nailed by the Gold Refining Forum. It is hard to imagine any way that radon – a gas at room temperature – (or any other gas) would remain at a temperature of 1,948oF, the melting point of gold. Gases don't like high temperatures. (You are just as likely to find a woolly mammoth in there). No radon, no radioactivity from it.

The problem with #2 is that, according to the Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity, 198Au has a half-life of 2.7 days, decaying into mercury. The short half-life means that less than 0.1% of it will remain after two weeks and essentially zero after a month. So, it is extremely unlikely that 198Au is the culprit. It would probably not be radioactive for long enough.

A more plausible explanation is that within the seed, the radon broke down into other radioactive elements with longer half-lives, Lead-210 (22 years), Bismuth-210 (5 days), and Polonium-210 (138 days). These new elements, all solids with high boiling points (see Note 2), "hung around," (except for the bismuth - too short a half-life) becoming long-lasting radioactive contaminants in the gold that caused the cancers. That's my story and I'm sticking by it. Until someone comes up with something better. (3)

Was this a big deal?

It certainly was a big deal to those who lost fingers, but otherwise, not so much. As I mentioned earlier, only 177 of 160,000 items tested (0.1%) were radioactive, A 1984 study reported that of 135 people who had been exposed to radioactive gold during the 1930s and 40s, 41 developed "mild to severe skin problems" and nine developed squamous cell carcinomas. Hardly a public health crisis, just an odd affliction that caught up to people a quarter of a century after they took their vows.

Speaking of vows, in 1984 Baptese and colleagues wrote:

"The incidence of skin cancer on the ring finger was eleven times that expected for men and forty-five times that expected for women."

Baptese, et.al, J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984 Jun;10(6):1019-23.

doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80327-8.

What the hell is going on here?? Why were women four times more likely than men to have dermatological issues from the rings? Is it possible that women kept their rings on, while men, being obligate pigs, frequently removed theirs to pursue extramarital delights? Nah, that's stupid, but just in case...

Men, keep those wedding rings on! Radioactivity notwithstanding, it's safer that way.

Ringless and busted. Free image: Corel Painter, PxHere

NOTES

(1) You and I both know that it is not a finger that would be cut off. Nuff siad.

(2) The boiling points of lead (3,180oF), bismuth (2,940oF), and polonium (1,746oF) would ensure that, unlike radon, these elements would stick around, even at the temperature of molten gold.

(3) Someone who does know what he's talking about is Andrew Karam, Ph.D., who wrote about radon (and radiation in general) for ACSH in 2021. See What's The Story With Radon? Really good article.