The research used our old friend, the UK Biobank, a repository of genetic information on a large number of Brits, as well as a similar genetic registry in Finland, the FinnGen. First caveat, the findings do not necessarily apply to racial and ethnic groups other than those studied. Because the researchers were interested in the loss of lifespan associated with habits and genes, they used quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) evil twin, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) – the cumulative years lost to disability.

Second caveat, because we are dealing with lots and lots of genetic profiles, there are any number of estimates and assumptions that go into these calculations – consider their qualitative rather than quantitative meanings. Among the assumptions,

- Most importantly, these genetic associations are causal,

- DALYs “are a valid and meaningful measure of disease burden.”

- DALYs lost from a specific disease are the same for genetic and lifestyle causes.

You may apply grains of salt, which by the way, is associated with an increase in DALYs, to taste.

Final caveat, the researchers linked the population's genetic data with the incidence of common diseases as measured by the Global Burden of Disease. Therefore, conditions that are more common and begin earlier in life will result in a more significant increase in DALYs; a greater loss of quality lifespan.

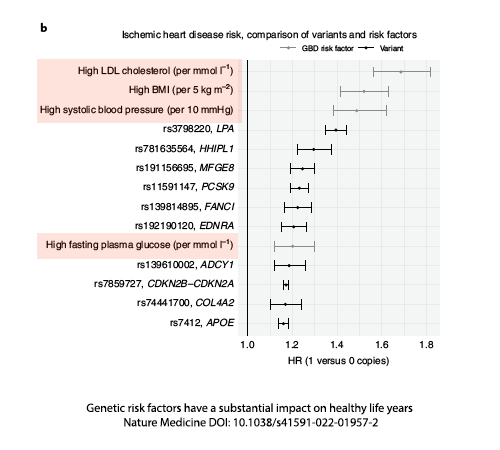

Common variants, genes with the highest association and probability of being causal with a disease, had a relatively small effect – a loss of 3 months. This includes the genes associated with “six traditional risk factor traits" (body mass index (BMI), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, systolic blood pressure and cigarettes per day).

Rare deleterious variants, genes we know are associated with disease, like BRCA1 for ovarian and breast cancer [1]. Here DALYswere much greater, resulting in anywhere from two to ten or more years of life.

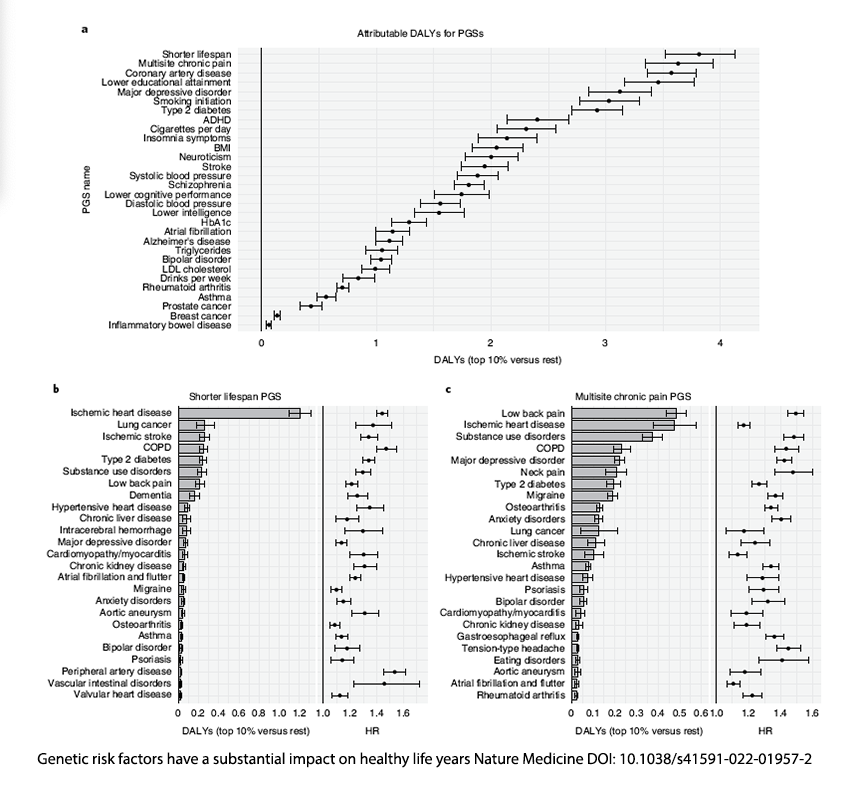

Polygenic scores measure many genetic variants associated with population-based traits or diseases. It is a catch-all grouping that you can read more about here or here. Here the researchers reported the difference between those in the bottom 10% of the cohort and the top 90% of the cohort.

To add to the complex meaning of these numbers, genetic variants associated with a shorter lifespan were, ready for it, the greatest source of increased DALYs – a circular definition, to be sure. Within that larger category, as depicted in the bottom left, ischemic heart disease was the greatest contributor resulting in a loss of 15 months of quality life. The contribution of other disorders like stroke and type 2 diabetes is one to two months. Interestingly, variants associated with multisite chronic pain were the second greatest source of disabled years led by low back pain – this is not surprising since the incidence of low back pain globally is 7.5% (for context, ischemic heart disease impacts 1.7% globally.

Sex-specific effects – gender resulted in different polygenic scores and common variants. The researchers found differences in the loss of quality life between the sexes, but this seemed to be due to a difference in their incidence rather than their disease course – more women developed Alzheimer’s Disease earlier than men resulting in the differences in DALYs; it wasn’t a more “severe” or different disease for the women over the men.

Enough with the data – Is it nature or nurture?

“by translating information on genetic risk into expected healthy life years lost, genetic risk factors can be put in the larger context of traditional risk factors….”

Individuals with rare deleterious variants have the greatest risk of disabled lifespans. Medicine already knows this, and we take active measures to screen and identify these individuals.

For most of us with common variants, modifiable risk factors are a more significant source of our disability than our genes. As I have highlighted, an elevated LDL, being overweight, and hypertension all increase your risk individually more than any of the genetic variations.

For most of us with common variants, modifiable risk factors are a more significant source of our disability than our genes. As I have highlighted, an elevated LDL, being overweight, and hypertension all increase your risk individually more than any of the genetic variations.

These should be good news because all of these can be modified through lifestyle and medications.

[1] Others included “LDLR (ischemic heart disease), BRCA2 (breast, ovarian, liver and prostate cancer, and COPD), MYBPC3 (cardiomyopathy and myocarditis), BRCA1 (breast and ovarian cancer) and MLH1 (colon and rectum cancer).”

Source: Genetic risk factors have a substantial impact on healthy life years Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-022-01957-2