P-values are the statistical coin of the realm in determining the significance, at least statistically, of a randomized controlled study – our gold standard. But might we apply a different metric to determine whether an impact is found? The researchers offer up the fragility index.

“It outlines the minimum number of participants in a positive trial who would need to have had a different outcome for the results of the trial to lose statistical significance. A lower number on the fragility index indicates that the statistical significance of the trial depends on fewer events.”

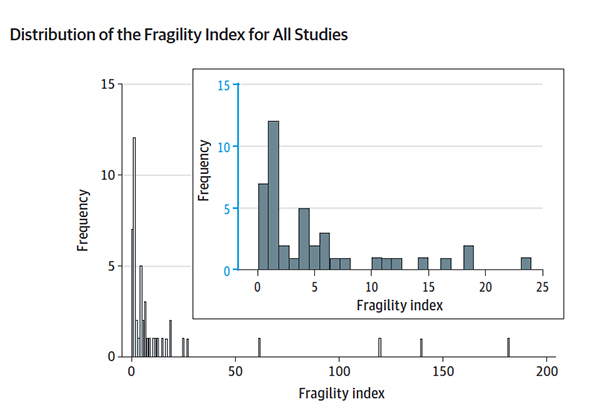

The indicator is intuitive; a low fragility index suggests that the finding may not be as robust clinically as it is statistically. [1] The researchers identified 47 peer-reviewed randomized controlled studies involving COVID-19, 77% for the efficacy of medications and 11% for vaccines. The median study group size was about 111 – remember, these were studies quickly pulled together in the early COVID-19 days as we ran from drug to drug looking for any form of effective treatment. Here are the outcomes.

The median fragility index was 4 – the number of events required to alter the statistical significance. For the studies of drugs, ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine come readily to mind; the index was 2.5 events. For the vaccines, that median fragility index was 119. In other terms, in 55% of the RCTs, less than a 1% change in the total sample would alter the results – I would call that fragile.

The median fragility index was 4 – the number of events required to alter the statistical significance. For the studies of drugs, ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine come readily to mind; the index was 2.5 events. For the vaccines, that median fragility index was 119. In other terms, in 55% of the RCTs, less than a 1% change in the total sample would alter the results – I would call that fragile.

“…a small fragility index does not imply that the study is not trustworthy. Small RCTs with low fragility indexes may still prove useful ….”

The fragility index is not an absolute. After all, larger studies with more events will tend to result in greater fragility indices – that was the case for the vaccine studies compared to some of the medication studies. The use of the index is further limited because it requires 1:1 randomization and binary outcomes. That said, it does offer a new lens in considering how best to proceed. A worthwhile finding with a high fragility index might push us to adopt the treatment more readily than a similar finding with a low fragility index. Those results might prompt more extensive trials rather than acceptance of trials based solely on statistical significance. This is one more way to try and ensure that when we scale up therapies, it is as valuable for a large audience as it was to the original participants.

[1] The fragility index is calculated by changing the number of events in the experimental and control group keeping the total the same. When the p-value’s significance is lost, you have the fragility index. If two cases alter the result, the index is 2

Source: The Fragility of Statistically Significant Results in Randomized Clinical Trials for COVID-19 JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2973