Emergency departments experienced a 30% decrease in overall use between 2019 and 2020, but they were not alone. Declines were seen in retail clinics, urgent care centers, and physician offices. Where did all those patients go?

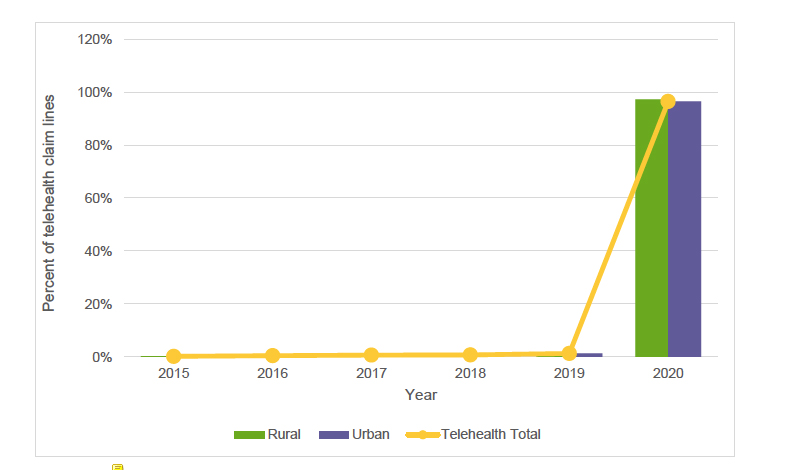

I have one word for you, telehealth. Remote care, motivated by an infectious disease, made big inroads last year – increasing 7,000% between 2019 and 2020.

“…telehealth grew in 2020 on a scale unseen in previous years.”

That is a dramatic change fueled by two significant trends—first, the self-imposed limitations of face-to-face encounters in physician offices. But more interestingly, unlike the other care locations, most patients were not seeking care for infectious disease, i.e., COVID. The bulk of these visits, 44%, were about mental health issues. That may help explain the more than a few thousand mental health apps now available on our phones. If we are looking for lasting changes, mental health is moving out of the office into remote care on our desktops and phones. With no need to touch, feel, or probe, at least with the physician's hands, this care can easily be distanced and a win-win for everyone. It allows more convenient, private access for patients and the ability for practitioners to provide care for a larger area than their neighborhood.

That is a dramatic change fueled by two significant trends—first, the self-imposed limitations of face-to-face encounters in physician offices. But more interestingly, unlike the other care locations, most patients were not seeking care for infectious disease, i.e., COVID. The bulk of these visits, 44%, were about mental health issues. That may help explain the more than a few thousand mental health apps now available on our phones. If we are looking for lasting changes, mental health is moving out of the office into remote care on our desktops and phones. With no need to touch, feel, or probe, at least with the physician's hands, this care can easily be distanced and a win-win for everyone. It allows more convenient, private access for patients and the ability for practitioners to provide care for a larger area than their neighborhood.

Retail Clinics and Urgent Care

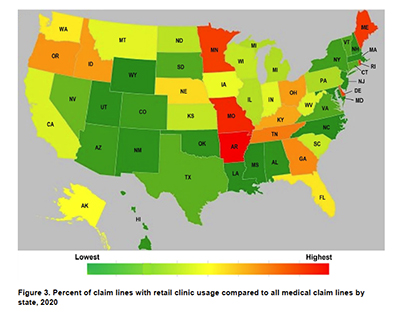

Here we are talking about those offices within a CVS, Walgreens, or Walmart, and those I pejoratively describe as “doc in the box,” corporate healthcare that looks a lot like the Chipotles of the healthcare industry. While their growth over the last few years has been touted at 30 or 40% or more, that number is misleading. Retail clinics account for 0.05% of total claims, and urgent care for 1.3%. They provide convenience, especially to those 31-40 years of age, their most frequent consumer. It is far easier to drop in over a minor ailment than to schedule and wait to be seen in a physician’s office. That said, their commercial placement constrains use. The map reveals no discernable pattern, and use is even less in rural areas than urban-suburban ones.

Here we are talking about those offices within a CVS, Walgreens, or Walmart, and those I pejoratively describe as “doc in the box,” corporate healthcare that looks a lot like the Chipotles of the healthcare industry. While their growth over the last few years has been touted at 30 or 40% or more, that number is misleading. Retail clinics account for 0.05% of total claims, and urgent care for 1.3%. They provide convenience, especially to those 31-40 years of age, their most frequent consumer. It is far easier to drop in over a minor ailment than to schedule and wait to be seen in a physician’s office. That said, their commercial placement constrains use. The map reveals no discernable pattern, and use is even less in rural areas than urban-suburban ones.

During the time of COVID, both acted as de facto diagnostic centers – 50% of visits to retail clinics were related to COVID exposure, symptoms, or need for immunization. For urgent care, the percentages were higher, 13% of their claims for “antigen detection” and another 60% for the office visits that accompanied that testing. We might want to consider how much extra we pay for convenience in the long term. Let’s consider payments.

While the difference between the “sticker price” for medications and their actual cost gets all the headlines, a similar phenomenon occurs for all medical fees – “charges” bear only a vague relationship to the amount “paid.” The cost of COVID care includes payment for immunizations and the “evaluation and management” of the patient. Payment for immunization has come from the feds and is consistent across all “care platforms.” Not so with those payments for evaluation and management.

Location, Location, Location

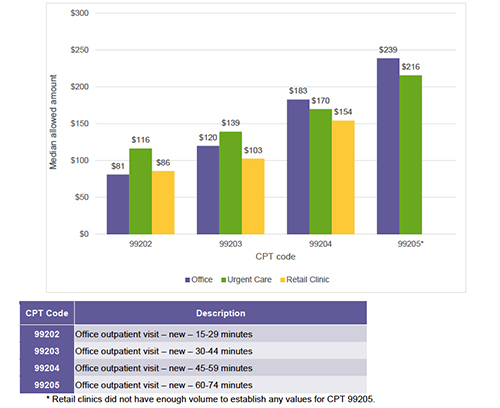

Some facilities are more expensive to run; they have costly imaging equipment and provide 24-hour care. While urgent care facilities may have an X-ray machine, the overhead for running these centers is low compared to an Emergency Department. More importantly, their overhead is comparable to a physician's office. That is not reflected in payments for care.

Care for the “worried well” and those with simple diagnostic problems, a sore throat, earache, or sprain, tend to gravitate to the quick in-and-out of retail, and urgent care, paid more than a physician in their office for identical services. As care becomes more complex (roughly consistent in the illustration by time spent with the patient), office-based care receives slightly higher rates than urgent care – retail centers do not even get involved.

Care for the “worried well” and those with simple diagnostic problems, a sore throat, earache, or sprain, tend to gravitate to the quick in-and-out of retail, and urgent care, paid more than a physician in their office for identical services. As care becomes more complex (roughly consistent in the illustration by time spent with the patient), office-based care receives slightly higher rates than urgent care – retail centers do not even get involved.

The shift of high-margin, low complexity care to more convenient locations gained traction with the pandemic, but it comes at a cost. That convenience of care, and I am not denying its value, costs you more in physician fees, $19 to $35 more (based on CPT codes 99202 and 99203). More critically, for physicians, it changes their mix of patients – removing the high margin, low complexity care leaves only the low-margin, highly complex patients. The $239 I receive for the hour of care to the complex (99205) is far less, by $93, than the four 15-minute patients (99202) that I might have seen.

This payment disparity and a desire for a work-life balance are significant factors in bringing an end to face-to-face consistent primary care. We are being penny wise and pound foolish. We should be careful what we wish for.

[1] The dataset includes privately insured and those participating in Medicare Advantage Programs but not traditional Medicare. The data do not include those insured by the government or the uninsured.

Source: FH® Healthcare Indicators and FH® Medical Price Index 2022 – A Fair Health Whitepaper