As if the Delta variant hasn't been a big enough pain in the a##, pretty much the last thing we need is an "improved" version. But there's a new nasty across the pond in the UK that is similar enough to Delta to be called AY.4.2, which is classified as a Delta subvariant rather than by a different Greek letter. And it's thought to be even more contagious (about 10%) than the original Delta.

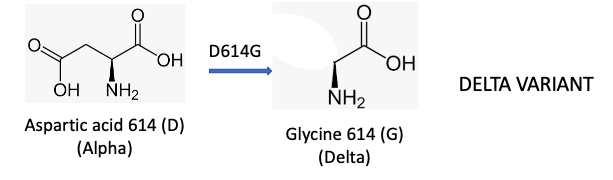

Delta was a result of a single amino acid change in the 1273 amino acid spike protein from that of the original virus – something I wrote about back in July. That's quite a bang for a handful of different atoms, but D614G – a substitution of glycine for aspartic acid at position 614 in the spike protein – was sufficient to seriously screw up the world (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Alpha variant mutated into the much worse Delta variant by switching one amino acid out 1273 in the spike protein. That's a change of only 0.08% of the protein, but look what it did.

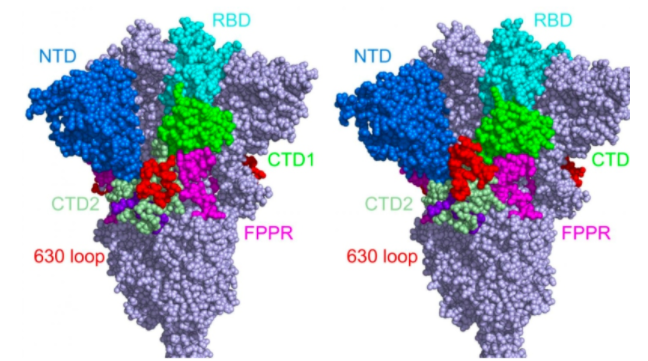

Consider how small this difference is while you're getting out your magnifying glasses (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The structures of the original spike protein (left) and the Delta variant (right) are almost identical, yet this was sufficient to unleash Delta upon the world. Credit: Bing Chen, Ph.D., Boston Children's Hospital, CTV News

"New and Improved" Delta

Delta AY.4.2 differs from Nasty Old Delta by two mutations: Y145H (histidine replacing tyrosine) at position 145 in the spike protein and A222V (valine replacing alanine) at position 222 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Delta AY.4.2 is the product of the original Delta variant with two different amino acid mutations.

Something to ponder: Why did Delta, which resulted from the substitution of one amino acid, get its own letter while Delta AY.4.2, with two amino acid substitutions, be labeled a subvariant? Educated guess: The properties of Alpha and Delta were very different while those of Delta and Delta AY.4.2 are not.

"It's nothing compared with what we saw with Alpha and Delta, which were something like 50 to 60 percent more transmissible. So we are talking about something quite subtle here and that is currently under investigation. It is likely to be up to 10 percent more transmissible. It's good that we are aware."

Professor Francois Balloux, director of University College London's Genetics Institute, in a BBC interview

What Now?

Probably nothing. Unlike the Alpha to Delta transformation, the emergence of Delta AY.4.2 appears to be less of a concern at this time, even though there has been a recent spike in cases in the UK (1). The vaccines + boosters will almost certainly continue to control serious COVID disease, and unvaccinated people will continue to become sick and die.

What's Next?

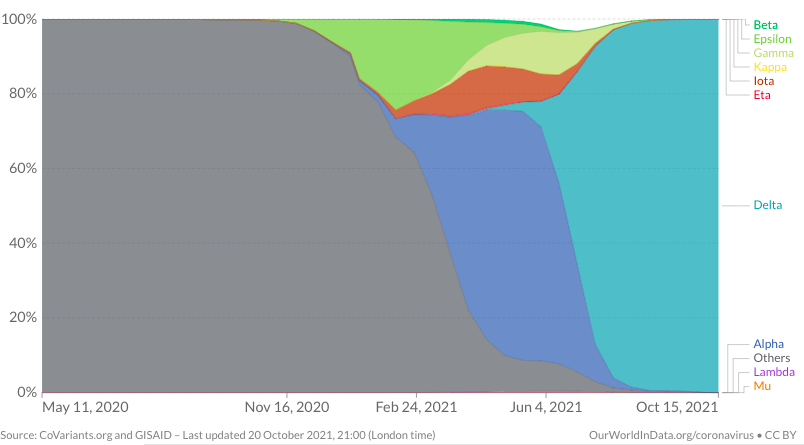

This is the more important question. The chart below (US) should make it clear that SARS-CoV-2 is nothing if not capable of mutation. Note what happened between winter and late spring. Although Delta is now firmly in control, there were still 10 circulating variants during this time.

Source: Our World in Data

Will we continue to see the emergence of new variants due to rapid mutation of the spike protein? Without doubt. Will there be any more unpleasant surprises, such as a new Delta? Impossible to predict.

What about treatment and prevention? Although we may need periodic vaccines, as is the case with influenza, there is no indication at this time that vaccines will become ineffective against emerging variants, however, this is possible. It should also be noted that molnupiravir (See Should Merck’s COVID Pill Be Granted Emergency Use Authorization?) was effective against the common variants. This makes sense since the variants differ by the structure of the spike protein and molnupiravir and the other direct-acting antiviral drugs in development target key steps in viral replication, which have nothing to do with the spike protein.

My best guess is that, between vaccination and antiviral drugs that are making their way through the clinic, COVID won't go away; it will just get booted off the front pages of newspapers, out of our (constant) thoughts, and become something comparable to influenza.

But we've all been fooled before.