Follow the money. No better words have been used to describe understanding the tangled economic web we may weave. A new paper from JAMA Internal Medicine demonstrates how, like Whack A Mole, reducing cost in one place may cause it to pop up and increase in another.

For some types of diagnostic testing, in this specific case, non-invasive cardiac tests [1], Medicare pays a fee to the physician to interpret the test and a “facility” fee to the site that actually performs the test. Irrespective of where the examination is performed, physicians receive the same payments for interpreting the test. But facility fees vary with the testing site. Hospitals with higher overhead costs [2] receive greater payments compared to the same examination performed in private offices or outpatient centers. But that was not always the case.

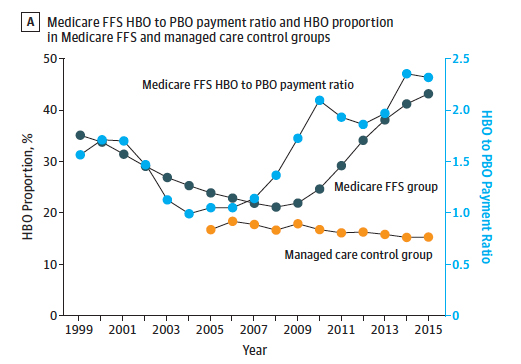

In 2005, Medicare recognized that it was paying provider-based facilities about the same as hospital-based facilities, more than their overhead required. CMS adjusted by reducing facility payment for these diagnostic tests performed in the office by about half. The theory was, reduce payment, reduce the incentive, reduce the number of tests – an economic version of lather, rinse, repeat. The researchers looked at subsequent Medicare payments from 2005 to 2015, in both conventional fee-for-service and managed care (Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, Oregon, and Washington). Here is the data; let us see whether you are surprised.

- By 2015, hospital payments had risen to roughly $700 (a 10% increase from the 2004 “baseline” and had decreased to $302 for office-based payments ( a 53% reduction from 2004).

- Testing rates in fee-for-service care initially rose and then declined by about 16%. During the same period, there were no significant changes in testing rates for managed care patients.

- In 2005, the ratio of hospital-based payments to office-based was roughly equal, 1.05. By 2015 that ratio was now 2.32 – the amount of testing done in that more expensive hospital setting had more than doubled. Again, those swings were not seen in managed care.

- The researchers calculated that despite an absolute reduction in the number of tests performed, the shift in examinations to the hospital resulted in “excess annual costs” to Medicare of about $500 million. Equally, if not, more importantly, that shift increased an individual beneficiary's out of pocket costs by $97 or about $161 million in aggregate.

There are several ideas we should unpack. First, given the differences in utilization between managed care and fee-for-service, you have to wonder whether economic or clinical concerns drive the use. I would hasten to add; those arguments apply to both. Second, it took health systems and physicians only a year to make the transition to more remunerative sites. Medicare payments changes do not occur in a vacuum; physicians and hospitals respond. It is no different from the cost of pharmaceuticals, lowering them here with a generic, raising them over there with a new class or form of medication. Medicare is not blind to the issue; they have been advised since 2014 to correct the “incentives” these differing payments create. But as the authors note, the problem is “politically contentious,” and a single, cost-neutral payment is currently being fought tooth and nail.

The accompanying editorial notes the unintended shifting payments of Medicare’s policy aimed at reducing expenses; and the increase out-of-pocket costs to the beneficiaries – a stealth cost because so few beneficiaries known of differential payments based on location, and they should not have to know. They raise one more concern; these differences may well push physician practices into health systems, further consolidating care. A physician practice can see an increase of roughly 14% in their revenue when their office becomes part of a hospital "campus."

The editorial puts it best, “for every action there is a reaction.” That is why healthcare spending is so maddeningly like Whack-a-Mole and follow the money is so often a guide to wasteful regulation and spending.

[1] These tests include various forms of stress testing searching for signs of clogged heart vessels as well as echocardiography, looking at the motion and function of the heart with ultrasound.

[2] Hospitals have larger physical plants, are open longer, have expensive equipment to pay-off, and all of these factors and more are used to calculate a cost to use the facility. Physician offices and outpatient centers do not have the same overhead and receive less in facility payments.

Source: Trends in Medicare Payment Rates for Noninvasive Cardiac Tests and Association with Testing Location JAMA Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4269

The Case Of Noninvasive Cardiac Testing – For Every Action There Is a Reaction JAMA Internal Medicine DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4265