Transcatheter aortic valve replacement, TAVR, is a far-less invasive means of replacing the heart valve connecting the heart with the aorta, the body’s main artery. It will, in no small degree, replace the traditional surgical repair, SAVR, over the next few years. How to diffuse its use across the US while maintaining its value, in both, functional outcome and fewer complications is a concern for the government, industry, physician and patient advocates. The question is, does size matter?

TAVR’s journey from the lab to the bedside

TAVR is a triumph of technology [1], and the story of its initial clinical use is fairly typical. Manufacturers of TAVR devices collaborate with academic centers that have both highly specialized/skilled physicians and a “wealth” of patients needing an aortic valve replacement in the initial application of these systems to patient care. They work with the patients who have no surgical alternatives in a very controlled and observed manner to demonstrate the device's benefits and risks providing the information in the application for commercial approval of these devices. In 2012, TAVR became commercially available to physicians outside the initial testing cycle.

It is a technology now available in 550 carefully selected centers. Since none of these new sites had ever used a TAVR device, the decisions about who and where qualified was based on a “surrogate” measures of operator skill, experience, and infrastructure – if you were a high volume center performing a lot of SAVR you had the requisite skills. High volume center is the critical phrase; volume is the surrogate. The problem facing device manufacturers, health systems, physician, and patients is what to do now, in the words of CMS how do you balance access with the surrogate measure volume – lowering the volume requirements will increase access, but will it also lead to less experience more episodic use in turn possibly resulting in more complications and deaths. [2]

Stakeholder positions

Manufacturers want to provide their devices to as many sites and patients as possible, this is their R&D payday. But they know that poor results will be disastrous, and they often employ their own criteria in the selection of physicians they provide their devices to and train. Health systems already providing TAVR are looking for more patients too, they already have proven their expertise so more centers will reduce their markets. Health systems without TAVR programs that only have surgical programs are appropriately fearful that their patients will opt for less invasive care and that their purely surgical volumes will drop along with those patient dollars. Same for physicians, those already doing TAVR want more patients, not more competition; physicians previously excluded from the party because of volume want a chance to provide the same care to their patients without sending them to some more or less distant center. Patients just want to be cared for safely and effectively.

The Problem

Physicians recognize that judgment, skill and experience are necessary components of all medical care, especially with this type of technology that requires device-specific training. During the commercial roll-out, volume was the best surrogate for experience with TAVR, but now with six years of experience, we understand the time necessary to learn techniques, some of the nuances of judgment and post-procedural care and we have statistics on the current outcomes, specifically deaths, complications and mid-range outcomes (months to years).

How to infuse these better measures in place of volume is the problem. But what is abundantly clear is that 1) increasing access in rural and underserved areas will result in low volume centers and 2) that when the volume is less than fifty cases, statistical analysis is problematic and just one complication or death makes the numbers look bad – it’s a sampling problem. Stakeholder positions, in part, motivate which side of the issue, access or accountability for quality one chooses. The numbers being discussed, whether 50 or 100 annual cases is sufficient for a center, are of interest only to the participants. For patients, the issue is perhaps how far they are willing or able to travel to be cared for safely. We should not let a discussion around what is the best surrogate measure cloud what is the real problem, how do we deploy our resources, should we always bring the doctor to the patients in a kind of 21st century house call; or is it sometimes better to bring the patient to the doctor, consolidating resources and experience.

As a veteran of two of these device battles, endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, and carotid stenting, I prejudged what the professional societies would suggest, and not in a good way. I was wrong, their position statement is thoughtful and a reasonable way forward. The discussion by CMS about how well volume translates to safety is also well taken; for TAVR the results are mixed. For one specific device 70% of the hospitals with volumes too low for statistical significance had no deaths, just like or better than higher volume centers. How we are going to regionalize the provision of expensive and highly advanced technology and skills are being formulated by these discussions.

There are two other features of the TAVR discussion worth mentioning to illuminate the thoughtful concern of all the stakeholders. First, there is agreement that all of the outcomes be recorded in a national registry so that hospitals and physicians have benchmarks to compare their performance and improve. Those registries already exist in a few forms, to what degree their findings will be made readily available in an informative way to the public remains unknown. Second, the decision as to the best treatment for aortic valve replacement, surgery, TAVR, or no care at all, is team-based, like the decision by “tumor boards” as to the best treatment for an individual patient’s cancer.

“… no one individual, group, or specialty possesses all the necessary skills for optimal patient outcomes. The success of these programs depends on a group of professionals, each with their own skillset, working together to provide the best possible patient-centered care.”

The use of data registries and real team-based care is upon us, not in words but deeds. While it may be cloaked in numbers and driven by a range of motivation we have learned from our prior efforts in diffusing medical technology. Good for us and good for you.

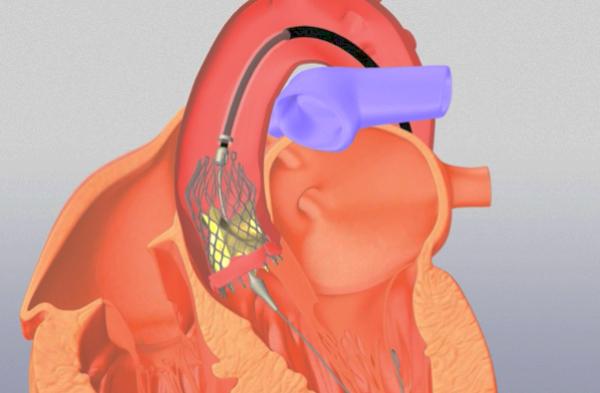

[1] Without going into details, a TAVR device is run from your groin’s femoral artery, 3/8” in diameter, about three feet to your heart, where it is opened to about 1” and replaces your aortic valve being fixed in place without stitches. Traditional surgery requires opening the chest, and carefully sewing a new valve in place while your heart is stopped and you are on bypass, where a machine temporarily circulates your blood supply keeping you alive.

[2] CMS is the regulator of TAVR utilization through its determination of who and where is paid to implant these devices – their national coverage determination (NCD). Public comment on the proposed NCD for TAVR are being made now with a new regulation in place by January 2019. Commercial insurers follow CMS’s lead.

Sources: 2018 AATS/ACC/SCAI/STS Expert Consensus Systems of Care Document: Operator and Institutional Recommendations and Requirements for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement JACC DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.002

Additional insight from MedPage Today’s reporting on TAVR