Criticism directed at the new director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in regards to his salary, seems misguided at the very least. Very troubling, bordering on hypocritical, is probably more like it.

After it was revealed that Dr. Robert Redfield was being comfortably compensated in his new position, why does it matter how his $375,000 salary compares to those of others top government officials? If you're a distinguished career professional with strong credentials and expertise, and if the essential position you accept requires that kind of burnished resume, what does it matter that you're getting paid better than your boss?

But instead of a prospective employee and an employer coming together and agreeing on a price that works for both parties – because, of course, government officials in the Health and Human Services Department benefited from bringing on such a qualified candidate – the invisible hand of the market is getting slapped down. After reports of Dr. Redfield's salary were publicly circulated, HHS announced late Monday afternoon that, bowing to public pressure and scrutiny, his pay will be downsized.

“Dr. Redfield has expressed to Secretary [Alex] Azar that he does not wish to have his compensation become a distraction for the important work of the C.D.C.,” according to an unnamed department spokeswoman, as reported by the The New York Times. “Therefore, consistent with Dr. Redfield’s request to the Secretary, Dr. Redfield’s compensation will be adjusted accordingly.”

“Dr. Redfield has expressed to Secretary [Alex] Azar that he does not wish to have his compensation become a distraction for the important work of the C.D.C.,” according to an unnamed department spokeswoman, as reported by the The New York Times. “Therefore, consistent with Dr. Redfield’s request to the Secretary, Dr. Redfield’s compensation will be adjusted accordingly.”

The amount of this downward adjustment was not immediately announced.

Dr. Redfield, a prominent AIDS and HIV researcher at the University of Maryland who was named to the CDC's director's position last month, reportedly earned more than $750,000 for the 12 months prior to his arrival in mid-March. Therefore, if that's true, he accepted a 50 percent pay cut to enter public service.

And now that's not good enough, despite that Dr. Redfield was "given the higher salary under a provision called Title 42," reported the newspaper. "It was created by Congress to allow federal agencies to offer compensation that is competitive with the private sector in order to attract top-notch scientists with expertise that the departments would not otherwise have." So the measure worked as designed, yet when it was revealed how top-notch the candidate was, the same lawmakers who enacted Title 42 determined that his compensation was an affront to Mr. Azar, as well as the heads of the FDA (Dr. Scott Gottlieb) and NIH (Dr. Francis Collins).

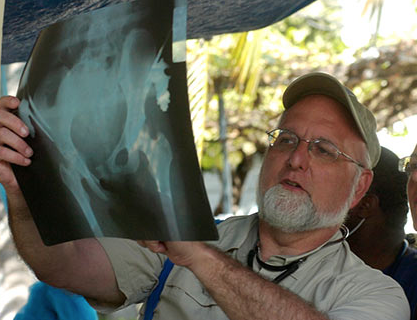

According to a statement released by the University, his previous employer, Dr. Redfield is a "renowned infectious disease expert, beginning his career in the late 1970’s" ... who "then co-founded the Institute of Human Virology in 1996," at Maryland. "During his military service, Dr. Redfield made several important scientific contributions to the early understanding of HIV/AIDS ... and at the Institute, Dr. Redfield’s research focused on novel strategies to innovatively target host cell pathways to treat and prevent HIV infection and other viral diseases." (Photo credit: IHV)

Prior to arriving, Dr. Redfield's predecessor, Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald, reportedly earned $197,300. Before her, Dr. Thomas Frieden, who was also an infectious disease specialist, held a salary of just under $220,000.

Shouldn't we be paying for value, for experience, for expertise? Of all the places to be searching for savings, this appears to be a very poor area in which to be focusing. It would seem that first eliminating wildly indulgent future expenditures – for example, $43,000 office phone booths, and completely unnecessary round-the-clock security details for other department heads – might be a better way to go than nipping at the heels of an expert with 40 years experience, who's decided to take a whole lot less in order serve the public.