Breast cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer among women (second to skin cancer) accounting for 29% of newly diagnosed cancers. Additionally, breast cancer is responsible for the second highest rate of cancer deaths among women (lung cancer is the first.)

In 2015, the numbers of diagnoses and deaths were approximately

- 231,800 cases of invasive breast cancer

- 60,300 cases of in situ breast cancer (a less invasive form of breast cancer)

- 40,300 deaths

- 2,350 men diagnosed with breast cancer and 440 deaths

Early detection is key for the best chance at recovery. The screening recommendations from the American Cancer Society, which seem to be a constant point of debate, are:

- Women ages 40 to 44 should have the choice to start annual breast cancer screening with mammograms if they wish to do so.

- Women age 45 to 54 should get mammograms every year.

- Women 55 and older should switch to mammograms every 2 years, or can continue yearly screening.

But some breast cancer specialists think that these recommendations fall short. Specifically, in the case of many women (roughly 40% of all women) that are told that they have "dense breasts." Most women do not fully understand what being categorized as having dense breasts means and that, in fact, it is an incredibly important piece of health information. It turns out that knowing your breast density status is very important in the conversation about breast cancer for a number of reasons. First, having dense breasts makes it more difficult to see inconsistencies through mammography that may lead to breast cancer in tissue. Also, the presence of dense breast tissue alone is a risk factor for breast cancer, although the increase in the level of risk remains unclear.

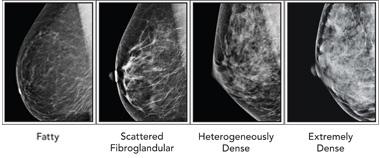

Although it is possible for some physicians to separate a very dense breast from a non-dense breast by a physical breast exam, the level of density is not possible to feel by touch. For that, physicians rely on mammography. Radiologists use a four category classification scheme when assessing the breast tissue on a mammogram called the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS).

The four classes, as indicated on the picture below, from left to right, are:

- Mostly fatty: The breasts are made up of mostly fat and contain little fibrous and glandular tissue. The mammogram would likely show anything that was abnormal.

- Scattered density: The breasts have quite a bit of fat, but there are a few areas of fibrous and glandular tissue.

- Consistent density: The breasts have many areas of fibrous and glandular tissue that are evenly distributed through the breasts. This can make it hard to see small masses in the breast.

- Extremely dense: The breasts have a lot of fibrous and glandular tissue. This may make it hard to see a cancer on a mammogram because the cancer can blend in with the normal tissue. (1)

In the above picture of the BI-RADS classification, the difference between dense and non-dense breasts seems clear. Technically, the last two of the four categories would fall under the umbrella category of "dense breasts." However, a recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, through the NIH / National Cancer Institute, suggests that the classification of breasts as dense actually varies tremendously between physicians.

In order to assess the consistency in breast density categorization between physicians, 83 radiologists who regularly interpret mammograms were asked to ascertain the breast density of 216,783 mammograms from roughly 145,000 women, between 40-89 years old.

In this study, an average of 36.9% of the mammograms were classified as showing dense breasts. However, the percentage from one physician to another varied drastically, with some radiologists determining 6.3% breasts as dense and others classifying 84.5% as dense. Another shocking result is that, for the 34,271 women who had consecutive mammograms assessed by two different radiologists, 17.2% (5,909) of their categorization changed with the second reading. Even when two mammograms were read by the same radiologist, there was a 10% change in dense versus non-dense status.

Even more concerning is the lack of transparency regarding this information. In about half of the states in the United States, you may not be told that you have dense breasts. Breast density notification laws have been put into effect in 27 states that require a notification about the dense breast classification to be given to the patient, however, they have long been criticized for being too difficult to understand. To find an interactive map with information on your state, you can go to the following link in order to find more information regarding your state's law; http://www.diagnosticimaging.com/breast-imaging/breast-density-notificat...

When Dr. Robert Bard, the Director of the Bard Cancer Center in NYC, a leader in the field of radiology, and a member of the Board of Scientific Advisors of ACSH, was asked whether he feels physicians are adequately explaining to women what the term dense breasts means for the health, his response was:

- “Unfortunately, for years and years they didn’t do it. They would simply say that there's nothing showing up on the mammogram, which means you could have extremely dense breasts — very high risk of cancer — and the mammography report would simply say, 'We don’t see any cancer,' which is a horrible misuse of these technologies. You should say, 'We don't see cancer, and we could be missing all of the cancer.' That’s the honest way to do it."

So, what can you do if you are told that you have dense breasts? There are other methods of visualizing breast tissue available, although they are not discussed routinely enough. For example, digital mammography, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of the breast and/or ultrasound are techniques that can be utilized in order to visualize inconsistencies in breast tissue. In regards to utilizing other technologies besides mammography, Dr. Robert Bard states that

- "The sonogram is better technology because we can see things under the skin that can’t be felt or are unclear. We can see things that the mammogram can miss completely — and even the MRI, if it’s too small, it won’t show."

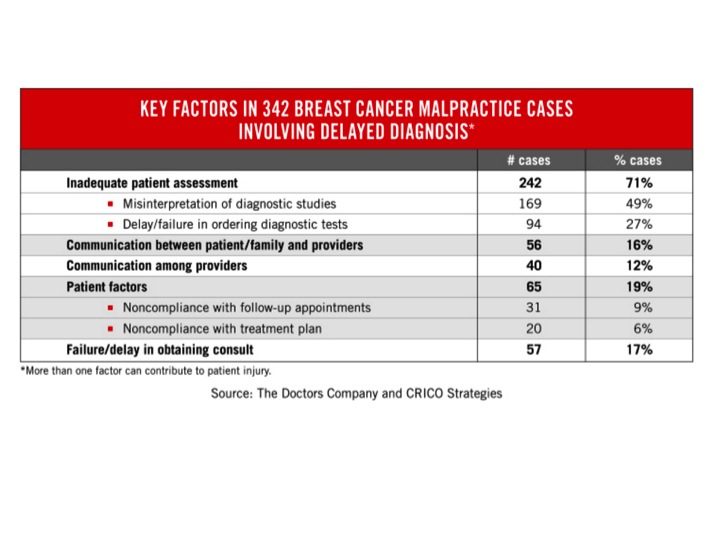

it is clear that mammography is limiting, especially in the case of a woman with dense breasts. However, the field is not responding quickly enough to this ongoing concern. A recent report put out by The Doctors Company illustrates the importance of clarifying this issue in the field of breast cancer diagnostics. They analyzed 562 breast cancer medical malpractice claims from 2009 to 2014 in the CRICO Strategies Comparative Benchmark System (CBS) - the medical malpractice insurer of the Harvard medical school community. In doing this, they found 342 cases of breast cancer malpractice due to delayed diagnosis, and roughly half of the total 342 involved radiology, more specifically, inadequate patient assessment and/or misinterpretation of diagnostic studies.

These large numbers of malpractice cases speak for themselves. There is a crisis in the field of breast cancer diagnosis and it is not being addressed adequately. As with all medical care, the classification of having dense breasts should be used as a jumping off point to deepen conversations and open up avenues for more thorough screening techniques. However, dense breasts are too frequently not communicated to the patient, or reported in a manner that leaves the patient confused and, therefore, not able to seek further treatment appropriately. The breast cancer field is ineffective in its current state when it comes to early detection of breast cancer in women with dense breasts, putting them at a higher risk for breast cancer.

References: