Efforts are ongoing to streamline criteria used to determine who would be an appropriate candidate for a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or what is commonly known as angioplasty.

A new article published in the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed what the growing body of evidence has continued to show. Specifically, that would be that there's no survival benefit observed in patients undergoing PCIs, versus optimal medical therapy alone, who have blockages in blood vessels, known as chronic stable ischemic heart disease.

WHAT IS ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE

Ischemic heart disease is when the blood vessels that feed the heart develop plaques that occlude blood flow to tissues, also known as ischemia.

Patients will experience this occlusion in the form of chest pain. In its most severe form, complete occlusion, patients will suffer a heart attack, resulting in death of the affected heart muscle. Stable angina occurs when the occlusion is less severe. When demands on the heart are increased, i.e. walking up a flight of steps, chest pain ensues which can be relieved by rest, or by taking nitroglycerin (helps to dilate blood vessels), or both. Unstable angina tends to happen with minimal exertion or even at rest unrelieved by discontinuation of activity or medication. This is the most dangerous form of angina as it can signal an impending heart attack and is a medical emergency.

There are two main types of treatment for symptoms associated with angina: medical and interventional (angiography + stent placement = angioplasty). The ultimate goal is to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

WHAT DOES PCI DO?

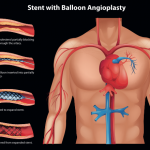

PCI, a procedure where a catheter is threaded through an artery up to the heart allowing the cardiologist to visualize blood vessels (angiography) to see where the occlusion is. A balloon at the tip of the catheter is dilated at the site of occlusion and a stent is placed to hold the vessel open, reestablishing the flow of blood.

A PCI is an appropriate form of treatment in patients with unstable angina or those who are experiencing an acute heart attack. Under these conditions angioplasty will always be viewed as an appropriate choice of therapy.

WHY THE CONTROVERSY?

Studies have shown that patients who have stable angina will experience relief of symptoms after an angioplasty but it does not equate to a survival benefit not more than medical treatment alone.

It is estimated that there are 600,000 angioplasties performed in the United States and the price tag is about $12 billion per year. PCIs are considered the bread and butter of interventional cardiologists. Concerns were raised about their potential overuse, which led to auditing of past procedures. PCIs deemed unnecessary resulted in adverse consequences for physicians and hospitals.

In 2009, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, as well as other professional organizations, released guidelines for appropriate criteria when selecting patients to undergo a PCI. A registry was created where hospitals would have their data published on performing PCIs, and if they were considered inappropriate. Their numbers were benchmarked against other hospitals. This level of transparency, and threats from insurers declining reimbursements, had a profound effect.

A paper recently published in JAMA, tracked hospitals from around the country to check trends for the appropriateness of PCIs performed from 2009 to 2011. It found that the numbers of people receiving a PCI for a heart attack, or unstable angina, remained stable (acute indications), the volume of patients receiving non-acute PCIs decreased, and the number of what was deemed inappropriate PCIs, also decreased from 26.2 percent to 13.3 percent.

NO LONG-TERM SURVIVAL BENEFIT

The NEJM originally published the COURAGE trial, a study that took place between June 1999 and January 2004 which tracked 2,287 patients with stable angina and divided them into two groups. One group received medical treatment alone and the second group received medical therapy as well as PCI. At a median follow-up of 4.6 years, there was no significant survival benefit of the PCI group versus the group that received medical treatment alone.

In the most recent issue of NEJM, an extended-follow-up of the original participants at 15 years, for whom data was available (about 53 percent of the original study participants), also did not find a survival difference between the groups receiving medical therapy and medical therapy plus PCI. This is yet another validation of previous studies that arrived at the same conclusion.