“Across eight studies and two experiments that spanned multiple platforms, time periods, and definitions of misinformation, our findings suggest that (i) misinformation sources evoke more outrage than do trustworthy news sources; (ii) outrage facilitates the spread of misinformation at least as strongly as trustworthy news…”

To reach their conclusion, researchers conducted eight observational analyses of 1 million Facebook and 68,000 Twitter postings and two behavioral experiments involving 1475 postings in a simulated social media environment. Links were classified as misinformation or trustworthy based on the source’s quality. Unlike prior investigations, the source checkers that determined a domain's [1] trustworthiness varied to create different domains for analysis. They were:

- Domain Dataset 1: Misinformation domains were derived from prior scholarly work supplemented with data from independent fact-checking and news quality organizations, e.g., FactCheck.org, Snopes, and Politifact. Trustworthy domains were sourced from similar lists excluding overlapping domains and included evaluations by Pew Research, US Newspaper Listing, and Station Index Broadcasting Information on top US-based news outlets. Subsequently, they were cross-referenced with tweets and threads from the Internet Research Agency (IRA). The IRA is a Russian organization “whose purpose was to sow disinformation and discord into American politics.” Its deliberate inclusion allowed comparison of misinformed and trustworthy information “that presumably were all shared with provocative intent.”

- Domain Dataset 2: Used Media Bias/Fact Check, Wikipedia, and US government reports to identify trustworthy and misinformation domains

- Domain Dataset 3: Contains 11,508 news domains sourced from diverse fact-checkers and those found in previously published research.

The behavioral studies utilized three domain databases, testing responses to fact-checked headlines categorized by trustworthiness (true/false) and outrage (high/low). Participants rated the likelihood of sharing or the perceived accuracy of the headlines [2]

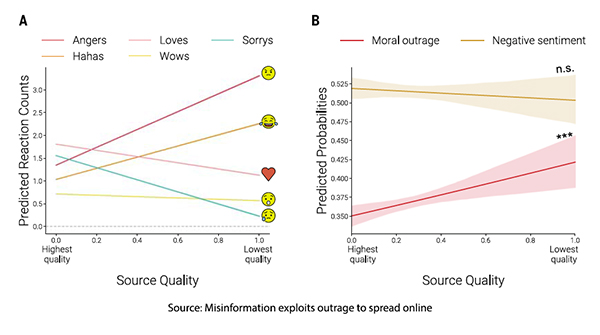

Misinformation sources consistently evoke more outrage than trustworthy ones.

Misinformation sources consistently evoke more outrage than trustworthy ones.

On Facebook, links from misinformation sources received significantly more "Anger Reactions" rather than reactions like “Love” or “Wow” compared to those from trustworthy sources. On Twitter, tweets linking to misinformation sources were significantly more likely to provoke outrage in responses than those linking to trustworthy sources.

Outrage Facilitates the Spread of Misinformation

On Facebook, Anger Reactions significantly increased the number of shares for trustworthy and misinformation sources, with a stronger effect observed for misinformation across all three domains. Likewise, tweets that evoked outrage on Twitter were more likely to be shared, regardless of whether they were linked to misinformation or trustworthy sources. Howeverf, the effect of outrage for misinformation was more significant in some web domains, while the effect of outrage in other domains was greater for trustworthy news. In the behavioral study, participants were more likely to share high-outrage headlines than low-outrage ones, regardless of whether the headlines were misinformation or trustworthy. There was no effect interaction between outrage and news source or after adjusting for political ideology.

Intent – Epistemic and Nonepistemic Motivation

- Epistemic motives intend to seek, share, and rely on accurate, truthful, and well-founded information, guided by a desire for knowledge, understanding, and clarity, often prioritizing factual correctness and evidence over emotional or social considerations.

- Nonepistemic motives influence behavior without concern for accuracy or truthfulness, prioritizing factors such as emotional expression, social identity, group loyalty, entertainment, habit, or personal benefit over the factual correctness of information.

On Facebook, links with more Anger Reactions were more likely to be shared without being clicked (SwoC), and the effect was stronger for misinformation links than for trustworthy ones, indicating outrage drives impulsive sharing of misinformation more than credible content. Interestingly, a similar pattern but less powerful was observed for other emotional reactions. In the behavioral study, participants discerned true headlines as more accurate than false ones; however, outrage did not significantly impact discernment, leading researchers to conclude that outrage encourages impulsive sharing rather than careful evaluation of content.

What Should We Do, If Anything?

“Moral outrage, specifically, is probably the most powerful form of content online.”

- Frank Bruni, journalist and Professor of the Practice of Journalism Duke University

Moral outrage allows us to express strong emotions without personal cost or commitment. It is “performative activism,” another way of value signaling. This is the second study I have discussed looking at spreading misinformation through social media. As a physician actively attempting to identify and spread scientific information, this is another concerning study. I join in with voices like Johnathan Haidt, asking us to pause and reconsider how social media changes our discourse and behavior. Yuval Harari writes about social networks that,

“Its defining feature is connection rather than representation, and information is whatever connects different points into a network. Information doesn’t necessarily inform us about things. Rather, it puts things in formation.”

Social media connects us, not through the content, but the emotions and responses we share – that is what puts us “in formation,” aligning us with our kindred spirits and cultural tribes. Craig Cormack, writing in The Science of Communicating Science, notes,

“…the more emotive somebody is about a topic, the less likely they are to be influenced by any facts and figures. … The more agitated, scared, upset or angry people are, the more receptive to emotive messages they are and less receptive to facts.”

By its very construction, social media favors the summary or the gist, and adding an emotional note accelerates tweets and threads. We can’t help it; we are hardwired by millennia of evolutionary events to respond quickly to fear and danger. It is a tool of our creation that we simply do not know how to use safely. As a result, again, in the words of Yuval Harari, echoed by Cormack,

“The naive view further believes that the solution to the problems caused by misinformation and disinformation is more information.”

There is a generational shift in how we get our news; unfortunately, this has been accompanied by a decreasing attention span. By its very nature, social media is not informative about complex issues; it simplifies to the point that it reflects a tenuous relationship with reality. It is the decrease in the depiction of reality that puts rational consideration at risk. We are best served by not using social media in its current form and requiring corporate overlords to make their platforms safer for not just kids or adolescents but for us all. The value of X or Facebook and its “network effect” lies with the users, you, and me. If we did not use those platforms for a week, we could demonstrate where the true power (and valuation) lies far more effectively than government regulation.

If moral outrage is the internet’s favorite energy drink, it’s time we reconsider the cost of guzzling it by the gallon. Social media, by design, thrives on our raw emotions, rewarding us with dopamine while it quietly erodes our ability to discern truth from fiction. The antidote isn’t more information or louder debates—it’s a deliberate pause before we click, share, or react. If we want to reclaim meaningful discourse, we must resist the pull of performative outrage and demand platforms that prioritize thoughtful engagement over emotional exploitation.

[1] Domains were used rather than individual articles to allow for scaling and create an adequate sample size. This introduced a degree of uncertainty about whether a specific linked article was misinformation.

[2] “In the task, all participants viewed 20 news headlines, 10 of which were trustworthy headlines and 10 of which were misinformation. Of the trustworthy and misinformation headlines, half were expected to evoke more moral outrage from people who identified as the same political party as the participant, and half were expected to evoke less moral outrage.”

Source: Misinformation exploits outrage to spread online Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adl2829