This study, published in Nature, focused on 1,787 adults living in 18 isolated villages in Honduras. The villages were chosen because they are a traditional setting, with face-to-face interactions, a traditional diet, and limited use of antibiotics and other medications. By asking

- "With whom do you spend free time?"

- "Who do you trust to talk about something personal or private?"

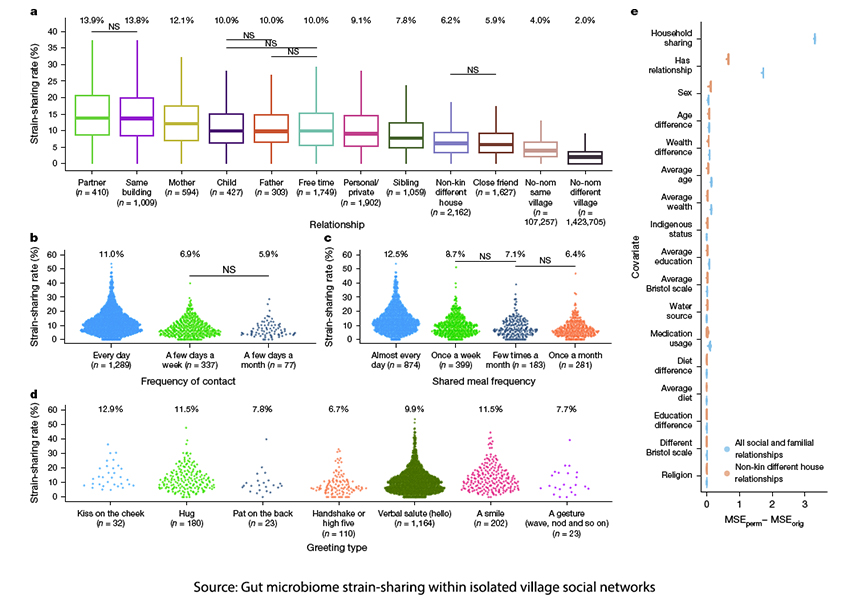

The researchers mapped the village's social networks, identifying social relationships, e.g., partner/spouse, sibling, close friend, and the frequency of contact, sharing of meals, and how they greeted one another.

The obtained microbiome samples from 50 to 75% of the people in each village characterizing it at the strain level – because shared strains imply a greater interpersonal transmission than one simply afforded by diet. They used a metagenomic computational tool to describe the strain-level similarity and diversity of participants' microbiomes as their microbial map of relationships.

Among their findings:

- People connected through various relationships share more microbial species and strains than those who are not connected. This applies to family relationships, friendships, and people who share free time or personal conversations.

- Strain sharing is higher among those who live in the same household or are spouses than other relationship types.

- Strain sharing extends to second-degree connections. A person's broader network, not just their immediate connections, influences the composition of their gut microbiome.

- More frequent social interactions and closer physical proximity increase strain sharing. Beyond household or familial relationships, this involved pairs who reported spending free time together or sharing meals more frequently.

Fun Fact – Mothers shared more of their microbiome with their children than fathers. However, before jumping to a conclusion about parenting, remember that mothers transmit their microbiome to their children at birth, at least for vaginal deliveries. This points out some of the difficulty in separating the impact of microbiome similarity in our relationships.

Can These Similarities Predict Relationships?

Short answer: yes. To arrive at that conclusion, the researchers built several models to predict whether any pair of people in a village has a social or familial tie based on their microbiome similarity. The models differ regarding what socio-demographic variables, like age or wealth, impacted prediction accuracy. Strain-sharing, even when used by itself, strongly predicted all relationships. The introduction of a variable describing microbiome similarity resulted in poorer predictions.

The researchers looked at a subset of 301 participants two years after their initial analysis. Strain sharing remained temporally stable – those participants sharing strains initially developed additional shared strains with their connections over time. Similarly, those pairs that were not sharing strains initially failed to develop increased sharing; for these small populations, you were not making new friends, at least over the two-year interval.

Network Position

Network analysis identifies nodes, in this case individuals, and then describes the linkages. Based on the number of linkages, one can detect the nodes that act as central hubs for clusters of individuals. Mathematically, it is described by a measure called network centrality. Microbiome sharing could be used to link individuals and identify these socially central individuals – individuals with a “paradox of popularity.” The researchers found that these central figures had microbiomes more similar to the overall social network (village) than their first-degree (directly linked) connections.

Individuals with what network analysis termed high clustering coefficients, part of groups where their friends are also friends with each other, tended to share more strains. Interestingly, clusters of socially interconnected individuals exhibit distinct microbiome profiles. Biology continues to teach us about our entangled relationships with one another and the environment.

Social Contagion

For the anchor author of this paper, Nicholas Christakis, this is not the first time at the rodeo. For over 30 years, he has explored the concept of social contagion how behaviors, attitudes, and emotions spread across networks of individuals. Through interpersonal influence, mimicry of behavior, a shared environment, and social norms, behaviors diffuse from individuals to their first- and second-degree networks.

“This was a kernel of an idea that I just couldn’t let go.”

- Nicholas Christakis MD, PhD, MPH, Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science Yale

He wrote a landmark paper in 2007, The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network over 32 Years. In that study, involving 12,000+ participants in the Framingham Heart Study, he found:

- Discernible clusters of obese individuals (BMI ≥30) were present at all times, extending up to “three degrees of separation.”

- A person’s chances of becoming obese increased by 57% if a friend became obese, by 40% if an adult sibling became obese, and by 37% if one spouse became obese.

There is also significant work demonstrating that obese individuals have unique microbiomes. For example, one study demonstrated differences in the ratio of two beneficial bacteria, Baceroidetes and Firmicutes, in obese individuals compared to lean individuals. For obese individuals, their ratio “normalized” towards that of the lean as they lost weight.

This current study provides a linkage between the two, a possible explanation for what seems to be the infectious spread of a phenotype, obesity. Perhaps it is the transmission of microbial strains that contribute, in part, to our obesity problems. The relative contribution of social connections and the microbiome to obesity remains unclear. Still, it is clear that our social relationships impact our health and that the microbiome is just one of many mediators. Our social structures create comfortable niches for its human members and the microbiomes they carry as not-so-silent travelers. As it turns out, not only are we what we eat, but at least for our microbiome, who we know and know well.

Sources: Gut microbiome strain-sharing within isolated village social networks Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08222-1

Your Friends Shape Your Microbiome—and So Do Their Friends Scientific American